Jakob built his 200-square-foot house and chicken coop out of discarded materials that he scrounged from construction sites.

In the hills of Northumberland, an inventive and visionary young man has established a sustainable, self-sufficient lifestyle. And there’s Wi-Fi, too.

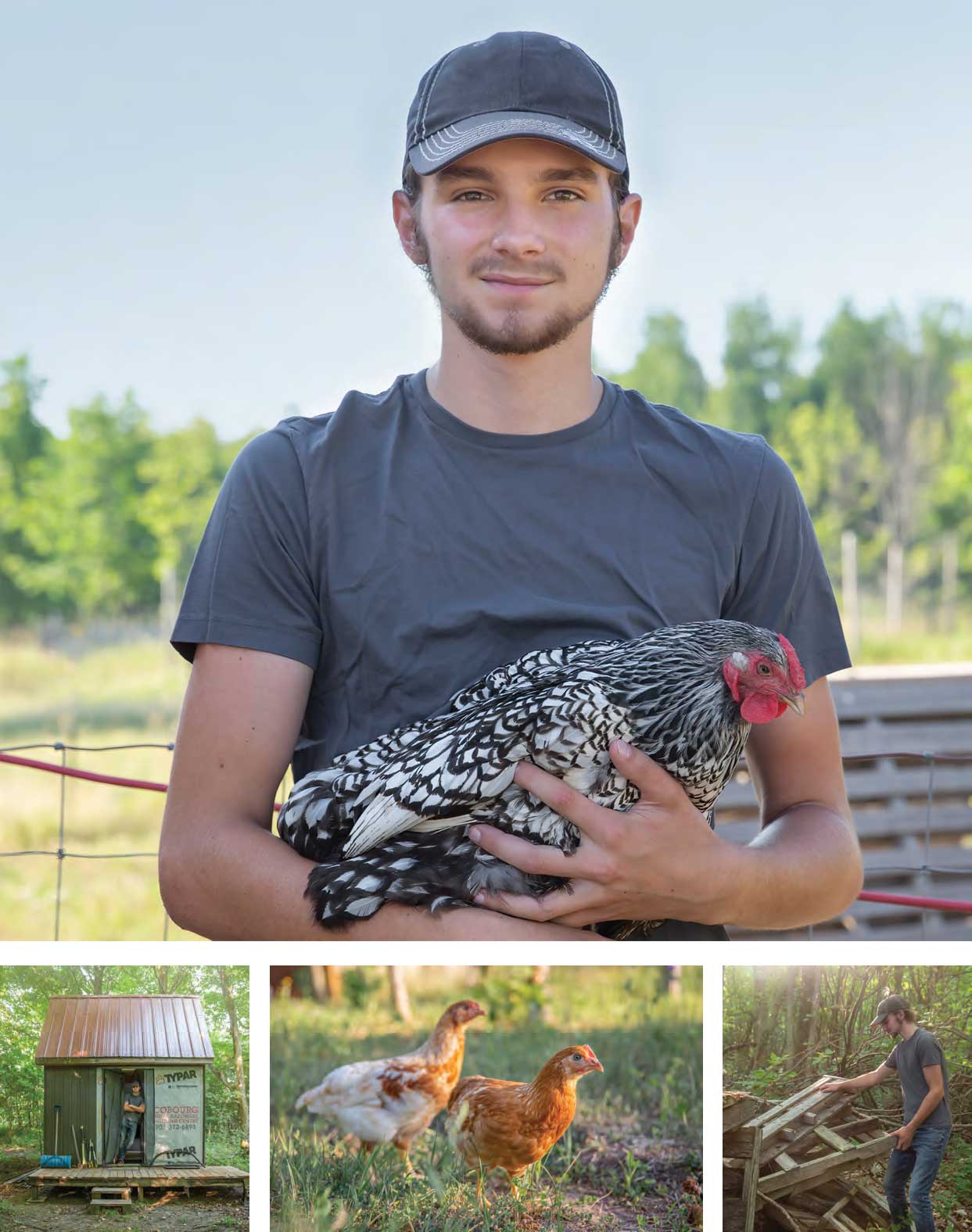

Atop one of Northumberland’s picturesque hills, where expansive views of Lake Ontario give way to carpets of undulating grasses and meadow flowers, Jakob Jenkins has built himself an off-grid house, a barn where he raises almost a hundred chickens, and some raised beds that are teeming with vegetables. Although micro-farming and even off-grid living are not unusual in Northumberland, what makes this scene unique is that Jakob just recently turned fifteen years old.

His tiny house, 200 square feet of lofted man-cave on his family’s 25-acre property, feels anything but cramped. It’s light and airy with finished walls, large insulated windows and laminate flooring. There’s a surprisingly large loft space used as a bedroom with an additional wall-mounted desk and a large open concept main floor complete with a small closet, a microwave, and a mini fridge.

There’s even enough room for guests to stretch out comfortably on a pull-out couch and watch TV while enjoying the warmth from the electric fireplace. And yes – he also has Wi-Fi. There are plans to add a full kitchen and a bathroom in the future.

“Most of my materials were scrap from construction sites that people let me have for free – like pallets and plywood,” Jakob explains. “It took a few months to build. I could have finished it in two weeks if I had worked on the house full time, but I had to take some odd jobs to get enough money for the solar panels, the fireplace and some tubing.”

“I was twelve at the time so there were not a lot of employment opportunities open to me,” he adds with a smile.

Despite being made with recycled construction materials, there is nothing to indicate the house’s tiny budget. His biggest purchases were the two 400-watt solar panels that supply all the power he needs for the appliances and the electric fireplace.

“The fireplace is OK for heat, but when I have the money I’ll buy myself a small woodstove so I can use all the felled trees from our woods. That’s more sustainable,” he comments.

Jakob seems like any typical teen: he likes to group chat with his network of friends, curate his social media persona and share the latest TikTok videos. So it comes as a surprise when he states, “I’ve wanted to be a farmer since I was three years old.”

Surprising also because neither his parents nor his grandparents are farmers. In fact, his mother is a Registered Massage Therapist and yoga and movement therapy instructor, and his father is a quality manager for a local manufacturing company. Although neither parent was raised on a farm, both are committed to finding ways to live more sustainably, which includes sourcing food in an environmentally responsible way.

“Sustainability and the environment have always been big considerations for Jakob, even before we were encouraging the kids to be more aware of where their food comes from,” says his mother, Erin Jenkins.

Erin also remembers Jakob showing early signs of entrepreneurial prowess as a little boy.

“We would be playing a board game called The Game of Life and Jakob wouldn’t buy the houses or cars, but rather invested in stocks for the ‘passive income’ he would collect. What five-year-old knows about passive income?” she laughs.

“I think there is nothing better than eating a meal that you have made yourself, in a place that you have built. I strongly recommend it.”

JAKOB JENKINS

So when Jakob asked to build a tiny house on the family property all by himself, his parents agreed.

“We knew he could do it. His dad helped him clear a spot in the woods, but he didn’t ask us for any additional help. He even installed the solar panels by himself,” recalls Erin.

When Jakob didn’t know what to do, he turned to the internet for support.

“I watched some ‘You Tubers’ who talked about how to build tiny houses and hook up the solar panels. Then I learned about building hives and how to look after bees, and that led to my reading about raising and harvesting chickens for meat, and how to build my own barn,” he explains.

Jakob’s self-reliant spirit was fuelled by this array of online homesteaders offering their successes and failures, in easily watchable video posts.

This plethora of internet experts has undeniably changed popular attitudes towards off-grid, sustainable living. As the number of homesteading blogs and urban chicken-keeping or solar oven-building websites increases, so too does the collective comfort level with renewables. Living off the grid no longer conjures up images of Susanna Moodie’s life of backbreaking labour, poverty and hardship in the woods. Instagram is now full of images of sumptuous meals featuring sourdough bread baked in backyard brick ovens, bowls of fresh eggs from your own chickens and colourful vegetables picked right from the yard. Jakob and his friends are more likely to consider sustainable living as something to aspire to rather than something to avoid.

“It’s always been a part of who I am. My lifestyle isn’t all that different from my friends, I just do farm chores in between checking my emails,” he adds with a smile.

Perhaps bolstered in part by their son’s success, his parents decided to build their own off-grid house and farm on the property, close to where Jakob built his tiny house.

“Dad had an idea to go on this off-grid adventure, and I was excited for it,” he recalls.

For Jakob, that also meant an opportunity to try his hand at building a barn, this time for his parents’ newly minted Thrive Acres Farm.

“It was definitely more of a challenge than the tiny house, but the process went pretty smoothly and it was a real happy moment for me,” he recalls.

For his own barn and chicken coop builds, Jakob recycled an old outdoor movie screen for the roofing, gleaned leftover plywood and materials from the house construction, and salvaged doors where he could find them. This time he splurged on ventilation and fencing.

“The chickens are free range, but because we are up on the hilltop and it’s all cleared, I had to build structures that would protect them from raccoons, foxes and coyotes. But mostly I had to protect them from the heat. The heat is actually a bigger problem than predators,” he states.

During the summer’s punishing heat wave, Jakob and his family were out misting the animals and making sure they didn’t suffer heat stroke. Despite his best efforts, some chickens were lost to both heat and predators.

This challenge has not dissuaded Jakob from continuing his off-grid farming experience. He has been able to sell some of his produce and eggs at local markets and raise enough money to add some additional livestock to the farm.

“We have lots of meadow land so I’m hoping to add a few beehives, sheep, pigs and dairy cows,” he says.

He is already working on a design for an additional barn and fencing. Although he acknowledges that off-grid living is not for everyone, he says, “I think there is nothing better than eating a meal that you have made yourself, in a place that you built. I strongly recommend it. Everyone should experience this in their lifetime.”

Tonight Jakob and his family will be enjoying a meal of roast chicken with fresh vegetables all grown and raised on their farm. They will sit out and watch another glorious sunset from their hilltop, untethered from the grid, but still connected to the things that are most cherished.

Story by:

Micol Marotti

Photography by:

Alana Lee