Driving along our rural roads, you’ve probably found yourself stuck behind a large piece of farm equipment as it rumbles along.

Tractors, combines and hay wagons and the fields of crops they serve are a defining characteristic of our local landscape; in Northumberland alone, nearly a third of the land is classified as agricultural, and area farmers have taken full advantage of the rich “Class 1 soils” that were left behind by the retreating glaciers. But have you ever wondered exactly what’s growing in all those fields you see while you’re waiting behind that tractor? While a patch of pumpkins may be easy to identify, it’s not so easy to tell a field of wheat from a field of barley.

With that in mind, here’s a quick field guide to some of our local crops…

WINTER WHEAT | Ontario is Canada’s winter wheat powerhouse, and in our three counties alone, 40,000 acres of it were cultivated in 2020/2021. The main difference between winter wheat and other varieties of wheat is the season when the seeds are sown. In this part of the province, winter wheat planting starts in September. During the fall, small green shoots emerge, then lie dormant during the winter and resume growth in early spring. Winter wheat is used to produce flour for yeast breads and other chewy grain products; it is also blended with soft spring wheat to produce all-purpose flour. Winter wheat is important to overall soil health, as it breaks down compaction, prevents erosion and adds soil carbon.

Identification: Winter wheat is an annual grass that grows on average to waist height, with upright tillers (the additional “stalks” that develop from underground buds on the main plant). Leaf blades are smooth near the base and rough near the tip on the upper side. Each head contains 30 to 50 wheat grains.

Did You Know: Seed origins are contentious but many botanists believe that our Canadian wheat varieties originated in Ukraine and made their way to Canada via Scotland. First plantings of winter wheat were recorded in late August of 1812.

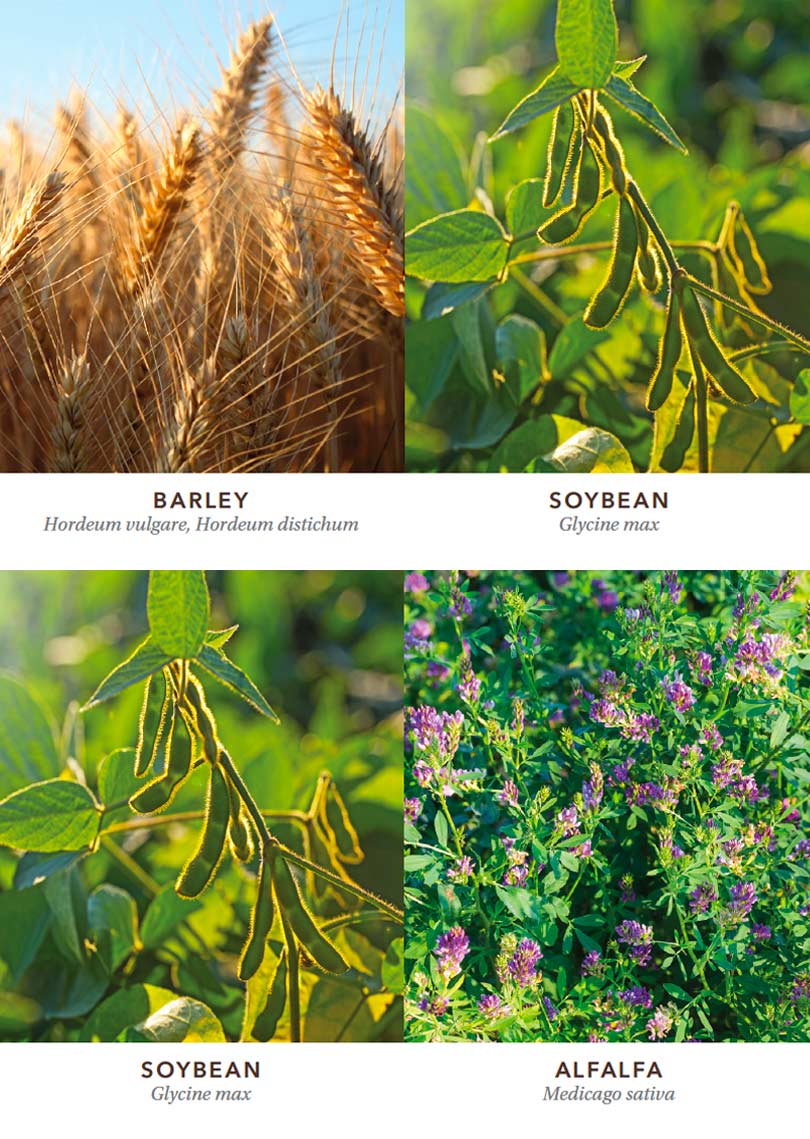

BARLEY | Barley is one of the most important cereal crops in the world, after rice, wheat and maize. Barley is packed with vitamin B and is widely used as a whole grain in our cereal and ground into flour. It is also one of the four essential ingredients in beer-brewing. An increased demand for Ontario malt has led to a strong market for Ontario-grown malting barley.

Identification: Like wheat, barley is a member of the grass family and it’s often difficult to tell them apart. When the barley plant matures, it has a few distinguishing features: the auricles – the ear-shaped areas where the grass branches from the stem – do not have hairs. Wheat auricles are much smaller and hairier. Barley has more seeds than wheat, producing 20-60 seeds, with the outer layer fused to the inner seed.

Did You Know: Barley is considered an excellent ally in the prevention of colon cancer.

SOYBEAN | Soybeans are fast becoming one of the most popular crops in Ontario, with 2 million acres grown last year. Soybean oil is a good source of omega-3 fatty acids and is used worldwide as a substitute for palm oil. Beyond its many food incarnations – such as soy milk and edamame – soybeans are also used to produce ink, plastics, textiles, candles, cleaning products, hair products and more.

Identification: The soybean is a branching legume with self-fertilizing purple and white flowers that develop into seed pods. It is harvested in the late fall when the plants have died back and the seed pods have dried.

Did You Know: In 1935, Ford Motor Company engineers even developed a plastic made of soybeans to build some of their car frames.

ALFALFA | Alfalfa is grown on almost 30 percent of Canada’s cropland and occupies 22 percent of the crop acreage in Ontario. It is often “interseeded” with wheat or corn. Alfalfa is used to produce hay and pasture for dairy cattle, as it provides high protein and energy for milk production. Like winter wheat, it prevents soil erosion and is included in crop rotations to help build nitrogen levels and improve soil permeability.

Identification: Alfalfa is a perennial flowering plant in the pea family. It resembles clover with its trifoliate leaves and long narrow leaflets that are serrated at the tips. Its flower is commonly purple, but can also be white or yellow. Alfalfa can grow knee high and has a deep root system, sometimes reaching out more than 15 metres (49 feet).

Did You Know: Alfalfa remains in a field for four to six years and fixes its own nitrogen from rhizobia bacteria found at its roots.

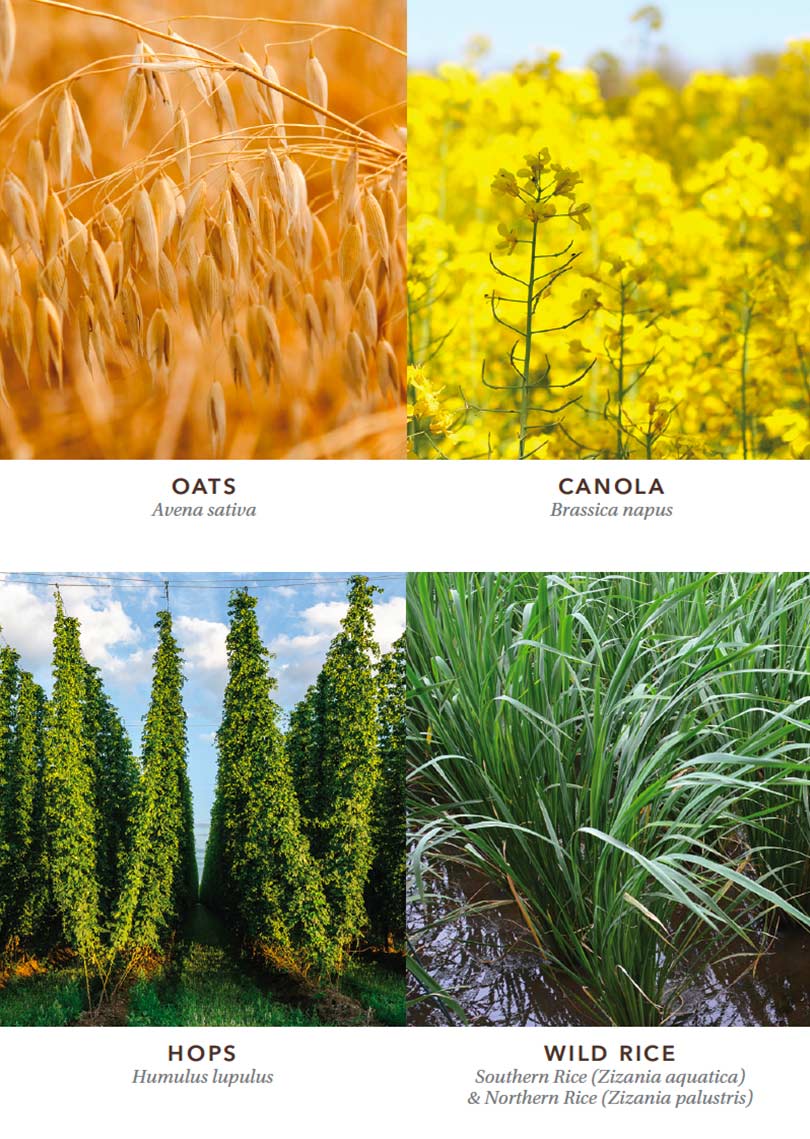

OATS | Although production has dropped in past years, 2.26 percent of Ontario’s oats harvest is still grown locally. While oats are primarily used for forage or feed, the higher quality grains provide us with cereals and oatmeal. Oats can grow well in poor soils that have a lot of moisture, and they have greater heat tolerance than many other cereal grains. Canada is among the world’s leading oat producers.

Identification: Oats, unlike barley and wheat, do not have an auricle. They have a greatly shortened stem, with leaves producing a rosette type of plant. Each plant has tillers, or branching buds from the fibrous root. An easy way to identify all oats from other cereals is to observe the twist of their leaves – the oat leaf has a counter-clockwise curl.

Did You Know: Wild oats are a pervasive weed throughout Ontario and a serious threat to annual grain crops. You can tell them apart from cultivated oats by their yellowish-green hues compared to the light bluish-green of cultivated oats, and by their hairy, dark-coloured, seed head with twisted, black awns (stiff bristles growing from the ear or flower of barley, rye, and many grasses) instead of the hairless, white ones of cultivated oats.

CANOLA | Canola belongs to the Brassica plant family, like mustard, broccoli, and cauliflower. Canola seeds contain about 45 percent oil. The oil, which contains the least amount of saturated fat of all culinary oils, is prized for its heart-healthy properties.

Identification: Canola is one of the easiest field crops to identify because of its small yellow flowers. Canola produces pods from which seeds are harvested and crushed to create canola oil and meal.

Did You Know: Canadian scientists used traditional plant breeding in the 1960s to eliminate two undesirable components of rapeseed – erucic acid from the oil and glucosinolates from the meal – and created “Canola,” a contraction of “Canadian” and “ola.”

HOPS | You may be seeing more trellised fields of hop plants in Prince Edward County, thanks to the growing number of craft breweries. Hops are used primarily as a flavouring and as a stability agent in beer. In addition to bitterness, they impart floral, fruity, or citrus flavours and aromas.

Identification: Hop plants are a non-woody perennial vine in the hemp family (Cannabinaceae). They are vigorous climbers that are usually trained to grow up strings in a hop field or hop garden. The hops used in the brewing industry are the dried, or fresh, flower clusters called cones.

Did You Know: If you rub the cone, the hop fragrance should be strong enough to identify the citrus aroma of Cascade or Centennial hop varieties grown locally.

WILD RICE | Although wild rice is not produced in the fields, it’s worth noting this important local crop and the efforts of the First Nation harvesters to re-seed areas in Rice Lake and within Alderville First Nation traditional territory and partner First Nations.

Wild rice was a staple food for the Anishinaabe and Algonquin peoples. The Anishinaabe call it manoomin, meaning “good seed” or “good berry.” In addition to providing food, wild rice is an important part of our small lake ecosystems.

Identification: Wild rice grows in shallow water in small lakes and slow-flowing streams. Only the flowering head rises above the water. Wild rice grains have a chewy outer sheath with a tender inner grain. Southern Rice is very rare and only identified along parts of the Trent-Severn Waterway. Locally, Northern Rice is found around Rice Lake.

Did You Know: Fluctuating water levels, shoreline development, dredging and the introduction of carp via Lake Ontario uprooted much of the remaining wild rice along the Trent-Severn Waterway.

Story by:

Micol Marotti