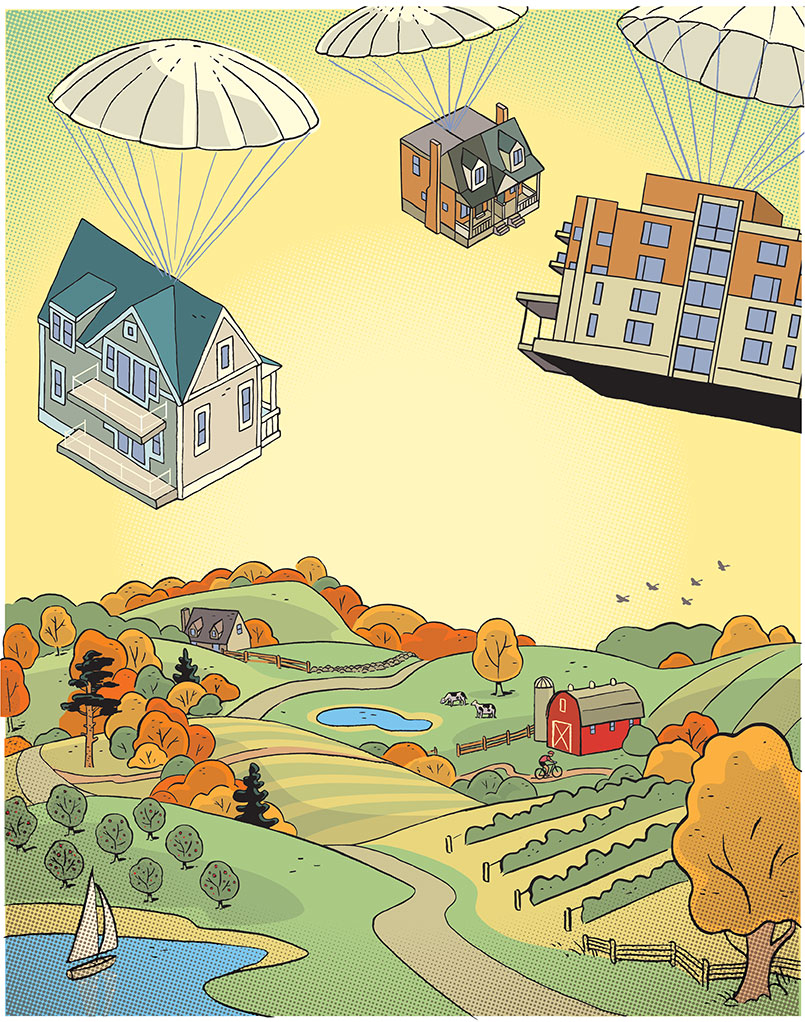

Population growth in our communities is inevitable. But giving a free hand to development without proper foresight, meaningful public engagement and strong civic planning will undermine the health of our communities for generations to come.

“Give us a place to stand

And a place to grow

And call this land

Ontario…”

It was 1967, and the theme song for the Oscar-winning film at the Ontario pavilion at Expo ’67 in Montreal was being sung everywhere. For those of us old enough and lucky enough to have attended Expo, both the song and dazzling film technique were captivating, the music a brain worm that engendered huge pride of place. This place, our place. Ontari-ari-ari-o. (Incidentally, the song was written by Vancouver native Dolores Claman, who also wrote the Hockey Night in Canada theme song.)

In the intervening 54 years, Ontario has grown, from a population of about 7 million in 1967, to 14.8 million in 2021. By 2046, it’s projected to be 20 million. Here are some more numbers from the provincial growth plan – A Place to Grow – for the Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH) area, which includes Northumberland County: Current population about 9 million, forecast population in 2051, 14.8 million. Net migration will account for 86% of growth and only 14% from people having children.

HOW MUCH ROOM IS THERE TO GROW?

The pace of growth will be less feverish in the eastern outer ring where we are: According to Dwayne Campbell, Northumberland’s Manager of Land Use Planning, the population of the county is expected to grow from its current 91,000 to 122,000 by 2051 – about 1,000 people per year – and most of that growth will occur in the six urban communities of Port Hope, Cobourg, Colborne, Brighton, Campbellford and Hastings. The goal of the plan is to increase density and diversity of housing within the settlement boundaries of existing communities because that’s where the infrastructure is: water and waste treatment, power, roads, schools and health care facilities.

Prince Edward County is just outside the GGH and is not included in A Place to Grow, but it has just completed a new Official Plan, which projects a total population of about 39,000 in 2038 (including seasonal residents), up from about 31,000 now. The focus of growth in PEC will be in Picton, Wellington and Consecon.

Of course, the 2021 census will put more solid numbers around all these forecasts and capture the urban exodus due to COVID, but for now these are the working numbers. And the fact remains, people continue to move here. There’s a housing shortage and the challenge is to accommodate the expanding population without sacrificing the rural character, heritage and poetic landscape that make this region so special. Change is difficult, change is inevitable, and as Heraclitus said, there is nothing permanent except change. But perhaps the one thing we can do is change our perspective about it.

A place to live

For you and me

With hopes as high

As the tallest tree

DEVELOPMENT OR DISASTER?

Driving through Watershed country these days, you can’t help but notice the ubiquitous development signs, wooing buyers with language like “Your Dream Home Awaits,” “Detached Homes starting in the mid $400s,” “Coming Soon: Waterfront Luxury Towns,” “Register Here: Lakeside Landing 17 Luxury Homes.”

When the heavy machinery rolls in, scouring the land to level it for building, a feeling of despair can take hold as another piece of farmland vanishes under the claws of a giant excavator. There’s fear in the air for those who have lived here for generations, or even a decade or so, that their way of life is disappearing, and you can hear and taste it at fractious council meetings when subdivision proposals are being debated. But wait a minute, is that fear justified? Are we living in a society where developers can build whatever they want wherever they want?

No, is the short answer. There are many checks and balances on development, starting with the Ontario Planning Act and working their way down through the fine print of Official Plans of other tiers of government to the zoning bylaws that govern what you can build on your own property. (Ministry Zoning orders that bypass this rigorous process are another highly contentious matter. See Landlab or Land Grab below.)

“It’s misunderstood by the public,” says Glenn McGlashon, who retired in August as Cobourg’s Director of Planning and Development. “Planning is integrated with everything. It’s complex and very detailed to make sure the public interest is protected. The goal is to create a complete community with a wide array of land uses – a mix of housing types and densities, access to open space, schools and parks, vibrant commercial and employment areas to keep consumer dollars in town. You can do this without harming character.”

To get a sense of the pace and complexity of what’s happening in Cobourg, population 20,000, you need only look at the July 26 report to Council: 23 housing developments in progress, 9 commercial enterprises and an assortment of other projects like the Golden Plough redevelopment. “On the financial side,” says McGlashon, “at just over the halfway point of 2021, the revenue derived from planning applications already sits at just over 121% of revenue budgeted for all of 2021.”

The pace is equally frantic in Prince Edward County, where, according to Planning Manager Michael Michaud, there are about 5,000 residential units in the pipeline throughout the County’s Settlement Areas. Who’s buying all of these places? David Cleave, a Picton developer who’s been building homes for 37 years, says it breaks down into five groups. “There are 75-year-olds who’ve had enough of rural life and are moving to town because they want lower maintenance and easy access to services.

When the heavy machinery rolls in, scouring the land to level it for building, a feeling of despair can take hold as another piece of farmland vanishes under the claws of a giant excavator.

There are retirees who grew up here, moved away and are now coming back. There are retirees from the GTA who are cashing out and buying smaller homes. There are Millennials who have demonstrated they can work from home, and there are immigrants to Canada who are building a new life here.”

MEET THE NEWCOMERS

Cleave works hard to design a mix of housing in his subdivisions at a range of prices to meet these various needs, from condos and townhouses to large detached homes. Phoebe and Pat Olszewski are a fresh-faced couple in their early 30s who epitomize the Toronto exodus brought on by COVID and are now happily ensconced in the Curtis Street subdivision in Picton. She works in marketing, he works in sales, and when the pandemic hit they were living in an 800-square-foot condo in Etobicoke with a toddler. “The building was filled with COVID and we were scared to even be there,” says Phoebe, holding 10-month-old Jasper while we stand in her huge, sunlit kitchen/living room. “We went up to my mom’s cabin in Haliburton. I was pregnant and both Pat and I were working, and my daughter Ruby was very busy!” she says. “It was stressful but we just didn’t feel safe in our condo.”

Phoebe, who grew up in suburban Thornhill, had always had a dream of living in a smaller community; her twin brother works in Wellington so they had visited him a lot and loved the County. In July 2020, she convinced Pat to take a run to Picton to look at old houses. But they never got to that. “We were on MLS and saw the layout for this place and reached out to Elyse Cleave. She took us on a tour of the street – it was really a construction site – and we went through one of the townhouses that was close to being finished. And it just seemed like such an outrageous amount of space compared to what we were used to, and that was the tipping point.” For Pat, there were a few non-negotiables. “If I’m moving out of the city I want a big house on a big lot,” he says. There was much to think about, so they went and had lunch with Phoebe’s brother, then drove back to Curtis Street and looked at the vacant lot that could become their new home. The house next door was already built and the neighbour was on the driveway. Phoebe got out and asked, “Do you mind talking to me? I’m thinking of buying a lot next door.” It was kismet. “She was my age and had two kids (now three) and talked about what an amazing community it was – great school, you can walk anywhere, lots of young families. We were sold!”

“We’re very decisive people,” says Pat, “and you know big risks equal big rewards in my mind, and this time we were rewarded.” They put down a deposit and there were shovels in the ground on August 18.

In September, Phoebe gave birth to Jasper and they sold their condo for about $660,000. Their new house, which cost $630,000, sped along on schedule and was move-in ready by the closing date of December 18. It’s 2,800 square feet, with four bedrooms and a playroom upstairs, a spacious home office on the main floor, a two-car garage and a gorgeous south-facing backyard that already has raised beds packed with vegetables.

Phoebe’s mom also moved from Toronto to Picton and bought a place in another one of David Cleave’s developments. She’s still working (from home) but is delighted to be close to her kids and grandkids, and like her daughter, has neighbours who have become good friends.

“It’s our forever home,” says Phoebe, handing Jasper to his dad and beaming. She’s already trying to convince some friends from Toronto to make the move – she is a marketer, after all. Frankly, some younger families would help balance the demographic, since the County currently has the highest proportion of seniors in all of Ontario.

DO MORE ARRIVALS MEAN HIGHER PRICES?

The Town of Brighton isn’t far behind. Jeff Wheeldon is a local realtor and he says Brighton has attracted a flood of retirees in recent years, and like everywhere else, low supply and high demand have driven prices through the roof (up 50% this July over July 2020). “It starts in downtown Toronto, where someone pays $3 million for a house (maybe a foreign buyer). It’s actually probably only worth $2 million,” says Wheeldon, as we sip coffee outside Lola’s. “So the seller has a windfall and moves out to, say, Port Hope, and overpays for a house. And now that seller has a windfall. There are concentric circles around Toronto and you can always make money moving east, until you get to Kingston and then prices go up.”

Some younger families would help balance the demographic, since the County currently has the highest proportion of seniors in all of Ontario.

This influx has been great for developers, but higher prices can lead to uniformity in the housing landscape and the creep of exclusivity. Driving through Brighton’s subdivisions south of Highway 2, there’s a sense of Pleasantville about them: manicured lawns, beautiful gardens, an eerie quiet, no strollers or bikes in the driveway, everything tidy and groomed to a fare-thee-well. It’s “pleasant,” but it also seems surreal. Where are the children, the playgrounds, the mix of housing types that create diverse, vibrant neighbourhoods? “In some of these neighbourhoods, it’s by design,” says Wheeldon. “Some condominiums have bylaws that don’t allow for play structures or toys in yards, or significant alterations to the exterior of homes, to keep the neighbourhood aesthetic. But a local developer has been deliberate about including variation in his latest neighbourhood, which includes homes ranging from $450K to over $900K on the same street.”

Affordability is a critical issue now, and one way to address it is with greater housing density: semis, townhouses, stacked townhouses, multiplexes. But these often get push-back from residents who are fearful that higher density and higher buildings will ruin the character of a town. David Cleave experienced this in his subdivision proposal for Talbot on the Trail in Picton. The original plan called for 290 units with starting prices at $325,000, but after contentious public meetings, the number of units was reduced to 230, and prices naturally went up. As of August 6, the price of the few remaining 1,200- square-foot townhouses was $475,000.

This is where theory meets reality. The new Official Plan for PEC, approved by the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing on July 8, 2021 (and running 233 pages!), states “To attract young families and professionals to the County, greater attention will be placed on providing a broader range of housing options such as rental accommodations close to community services and amenities.” The vision statement further says, “New development will be reviewed through the lenses of sustainability, agriculturally-focused, diverse cultural and economic fabric and healthy, complete communities. All new development will be compatible with its surrounding context, champion the protection of rural habitats and the natural environment, and, where possible, reduce the climate impact of our decisions.”

DO LOCAL PLANS HAVE ANY TEETH?

Glenn McGlashon is candid about the capacity of local planning departments to require developers to include affordable units. “We don’t have the tools to enforce that. We ask that they try to include them – we promote, coax and encourage not only affordable units but ones that are accessible and sustainable – but the existing Provincial legislation is geared toward larger urban areas and is limited in its scope for smaller centres like Cobourg.” The one tool planners can employ is a Community Improvement Plan (CIP), which local councils can adopt under The Planning Act. Cobourg has three of them: Downtown Vitalization, the Tannery District, and Affordable and Rental Housing. The latter CIP was only approved by council last December and will start to be implemented this fall. “It will allow us to offer a number of incentives to developers, such as reduced application fees and development charges, grants and loans, and property tax relief to stimulate the creation of the types of housing the community needs,” says McGlashon.

Let’s hope it works, because a quick search of MLS for properties under $400,000 in Cobourg reveals just one condo at $399,900, and these days we all know the asking price has little to do with the selling price.

Port Hope is equally inflated, but it’s not affordability that’s galvanized the town, it’s a small forest, a woods in fact: Penryn Woods. SAVE OUR TREES signs dot every other lawn in the west end of town near the Lakeside Village Mason Homes development. The community began to organize in March 2020 when people discovered Mason Homes planned to clear-cut the last stand of mature trees along Victoria Street to make way for Phase 5 of its housing development.

“We registered as a non-profit and hoped to act as a community voice supporting the municipality to challenge the clear-cutting,” says Claire Holloway Wadhwani, a local activist and mother of three young kids. “But over the past year, we got the sense we were not seen as a partner with Council.”

The group, officially registered as PHorests 4R PHuture, obtained its own legal counsel to speak at the Local Planning Appeal Tribunal (LPAT) hearing about the issue, but was stunned when the mayor announced the town council had voted in a closed-door session to have a two-stage hearing process, separating the Penryn woodlot from the other development lands. This allowed Mason Homes to continue work on Phase 5 and return to LPAT with a plan for Penryn Woods in the late fall. “Our spirits are low, we think we’ve lost the battle,” says Holloway Wadhwani, though the non-profit continues to advocate for sustainable environmental policies in Port Hope.

The lack of transparency and proper public engagement about Penryn Woods speak to a much larger issue about the whole development approval process. Politics, for one, but also good and timely communication. Planners work hard to design our communities, but the methods of getting information out to people – jargony notices in local newspapers, site plan billboards on properties – are not effective. As Dave Meslin writes in his book Teardown: Rebuilding Democracy from the Ground Up, “When it comes to hearing from our local governments, we desperately need a massive dose of creativity. Good design, plain language and data visualization are fundamental to public participation.”

But as citizens we also have work to do to ensure the developments that go in today will make sense 30 years from now. Think about affordability, diversity, sustainability, climate change adaptation. “There’s so much online now – Official Plan, Zoning Bylaws, planning process, etc. – people need to educate themselves about how government works,” says PEC’s Michael Michaud. “Get involved, do your homework and trust that we’re working for you to try to create healthy communities and good places to live.”

Landlab or Land Grab?

If you want to find out what’s controversial in Alnwick/ Haldimand, Brighton and Cramahe, a good place to start is activist Gritt Koehl’s website abcactivism.ca. Gritt and her husband Ernie built their retirement dream home in Grafton’s Haldimand Valley Estates in 2003. Her activism started in 2015, lobbying to stop train whistles at level crossings in Cramahe. Since then, she’s had an eagle eye on the councils of all three municipalities, monitoring their decisions and advocating for transparency and sound fiscal management.

The latest focus of her tireless energy is a development concept for 700-800 houses on 200 acres fronting Lake Ontario between Wicklow Beach and Lakeport. It’s called Landlab Lakeport Beach, and it would drop a new community the size of Colborne (2,000 people) on a piece of farmland surrounded by … farms. What about water and sewage, what about traffic, what about schools and stores? What are the developers thinking?

The new urbanism concept looks dreamy on Landlab’s website: quaint houses with front porches, paths, lots of public greenspace, including a 1-kilometre beach. But it’s stirred up a hornet’s nest of anger from area residents, including local farmer Ben Mazurek. “I don’t know one person around here who’s for it,” says the 32-year-old, who rents land east and west of the site to grow his crops. “Nothing like this has ever been proposed in Northumberland. To make a whole new town in the middle of nowhere is crazy. And don’t they know there’s little-to-no water in the summertime from Lakeport to Grafton.”

Ah yes, water and sewage treatment, crucial for any development proposal. Apparently, Landlab approached the Municipality of Cramahe first to see if they could tap into the waste water treatment plant in Colborne, but no, that was not happening. According to Mayor Mandy Martin, that water and sewage capacity is already accounted for with 200 new houses on the books. Next stop for Landlab was a presentation to the Alnwick/Haldimand Town Council on May 28, who seemed excited by the idea. Gritt attended via Zoom and then dove in and wrote a cogent letter to Council on June 7, itemizing all the ways the proposal contravened the Official Plans of both Alnwick/Haldimand and Northumberland County (you can read it on her site), and the next full discussion was at the Council meeting on June 24. (There are thorny issues about this property that date to a 2006 subdivision application by the previous owner for about 68 lots on wells and septics that is still before the Local Planning Appeal Tribunal.)

So where is it at now? On Sept. 2, representatives from Landlab appeared before Council, asking for its support for a Ministry Zoning Order (MZO) to clear the regulatory uncertainty and establish a framework for proceeding. “Without an MZO, we’re all stuck at the starting line with no road ahead,” said Landlab president Sean McAdam. At first there was dead silence after the developer’s presentation, not a single question from Council, then Councillor Mike Filip asked about the traffic implications of the project, stating there are four railway crossings nearby and a minimum of 88 trains every day. McAdam responded that the traffic study Landlab commissioned concluded there was no traffic concern.

An energetic discussion ensued, examining the rationale for an MZO as opposed to going through the regular planning process. After about an hour of debate, Council voted 3-2 not to support Landlab’s request for an MZO. It’s doubtful the project is dead, but this is clearly a major setback for the developer.

The Impact of Severances

Severing a lot or two from a large property is one way to capitalize on the surging value of land, and in the case of some farmers, fund retirement. But it can result in a fractured landscape of small properties – witness the sprouting of new houses along Highway 2 between Grafton and Brighton – that detracts from the overall rural character.

Each municipality has its own rules about severances. In Prince Edward County, for example, prior to its just-minted Official Plan (OP), landowners could sever two lots of a minimum of two acres. “We had a run-up of applications before the new OP,” says Planning Manager Michael Michaud. As of July 8, people can only sever one lot in the County, “and we’ve eliminated country lot subdivisions,” adds Michaud.

In Northumberland County, property owners typically sever two to three lots at a time, according to Manager of Land Use Planning Dwayne Campbell. “We encourage a limit of about three,” he says.

If you’re concerned about severances, contact your local municipality to find out what’s allowed and what’s not.

Story by:

Denny Manchee

Illustration by:

Carl Wiens