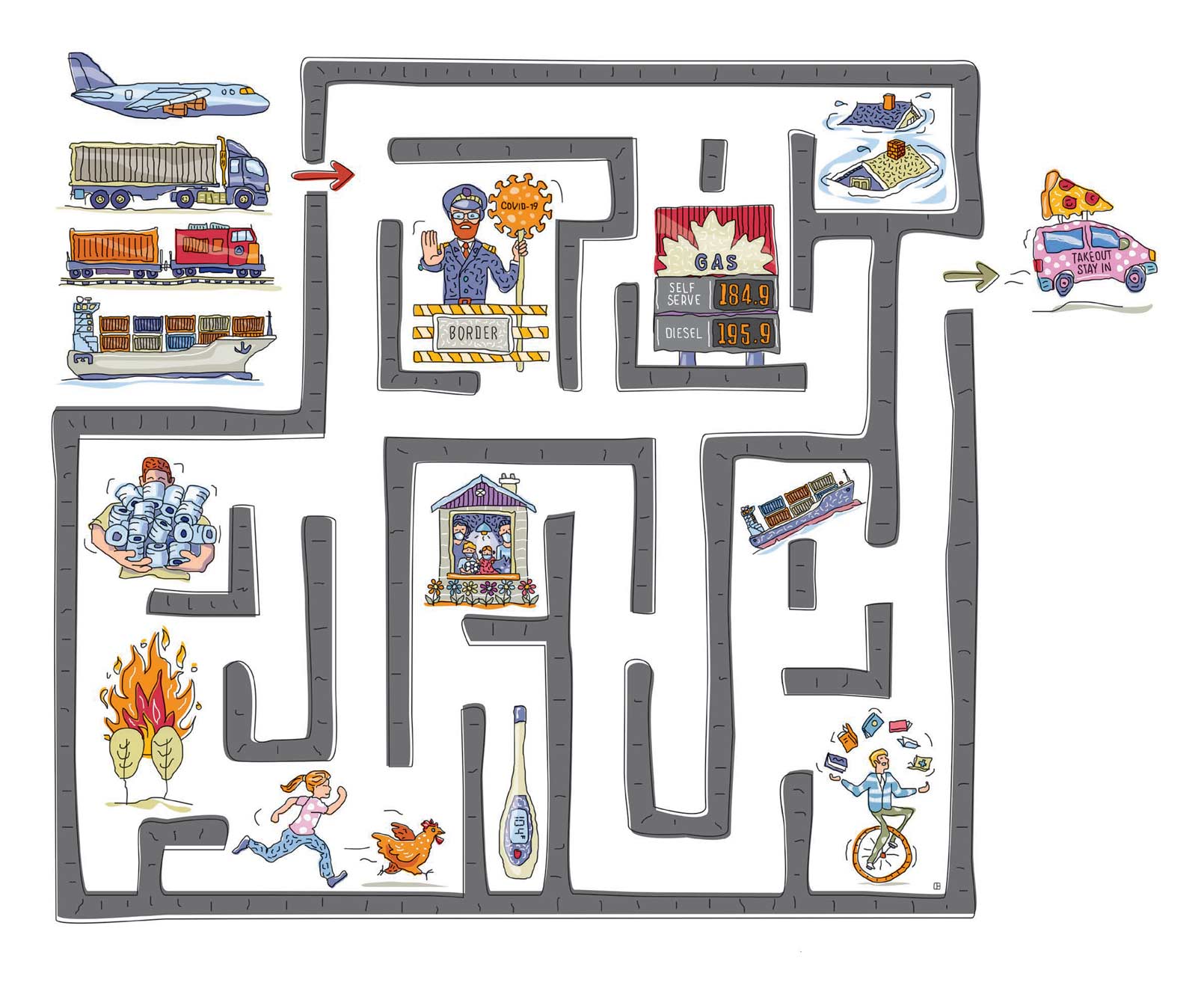

One by one, the links in the supply chain are being strengthened by the resilience of local merchants.

For Tracy Croft, the disruption began with toilet paper. Croft, the chef and kitchen manager at The Tower of Port Hope retirement residence, is also responsible for maintaining the Tower’s inventory of food and domestic supplies. In March 2020, a few days into the first COVID lockdown, she was surprised when The Tower’s longtime wholesaler announced that they were running low on toilet paper. A trip to the grocery store revealed a sight increasingly familiar to many Canadians: aisles of boring but essential basics such as toilet paper, paper towels, flour and sugar emptied by panicked consumers.

The run on toilet paper soon ended as Canadians adjusted to the new normal, but the other shortages were only beginning. Soon Croft was scrambling to replace chicken, vegetables, beef, soup and flour. “It’s never the same thing twice in a row,” she says. “One week it was chicken, the next it was baby carrots. It was really tough to do menu planning.” Almost two years later, Croft is still making occasional lastminute grocery store runs to make up for shortages.

Over in Belleville, Keenan Sprague, the co-owner of Sprague Foods, a manufacturer of organic canned soups and vegetables, has been forced to adjust to a shortage of machine parts, packaging and raw ingredients that started in the early days of the pandemic. “These shortages have resulted in longer order lead times and higher prices,” says Sprague. “The cost of transportation has also skyrocketed.”

And in Picton, David Sweet, co-owner of independent bookstore Books & Company, says that during the pandemic, he’s often felt more like a “juggler” than a bookseller. The lockdowns and restrictions drove up demand for cookbooks and gardening books and non-book items like puzzles and board games; at the same time, shipping delays and inventory shortages have made those popular items harder to procure. “There have also been huge price leaps in the non-book items we carry,” says Sweet. “Some puzzles and games have gone up as much as 30 percent, and one large puzzle manufacturer hasn’t been able to deliver any stock since last year.” This has kept him working the phones with multiple distributors and manufacturers to make up for shortfalls.

Three different local businesses, three different local communities – all impacted by breaks in a global supply chain most of us never thought about before the COVID crisis. Pat Campbell of Supply Chain Canada understands why. “Supply chains are complex,” says Campbell, vice-president of strategic initiatives with the national education and advocacy group for supply chain professionals. “They’re comprised of many discrete participants and functions, all of which combine to get goods to consumers. Global supply chains have been stressed since before COVID. We’re increasingly seeing long-standing weaknesses in our supply chain systems being exposed.”

A TRILLION-DOLLAR CHAIN

Canada’s supply chain alone – made up of manufacturers, retail and wholesale outlets, warehouses, shipping companies, transportation infrastructure, and millions of specialized workers – moves over $1 trillion worth of goods annually. Apply those numbers to global trade and – well, you’d better dust off that high school calculator.

Like the hypothetical butterfly wing flutter that triggers a tsunami half a world away, a delay in a Taiwanese factory can stall a production line in Michigan.

How did we get here? Nations have always traded goods across continents and oceans, but over the last half century, technological advances and trade agreements accelerated the transition to a vast interdependent global economic system. Within this web of interconnected economies, individual nations have moved toward specialization. Some countries focus on the production of manufactured goods – such as China, Taiwan, Bangladesh – while others, like Saudi Arabia and Venezuela provide raw materials such as petroleum. Still other nations such as the U.K. and Switzerland handle financial and management services of the global supply chain.

Most nations diversify their economies to some degree, but the trend toward specialization has created a global economy in which the components of a single product, such as a tractor, are likely to be assembled in one country from parts sourced from other nations across the globe. The arrangement makes for cheaper consumer goods and the free flow of products and services, but it also relies on a fantastically complex – and, as the COVID crisis revealed, frighteningly fragile – supply chain infrastructure that includes ports, rail lines, highways and airports. Like the hypothetical butterfly wing flutter that triggers a tsunami half a world away, a minor delay in a Taiwanese factory has the power to slow down an entire production line in Michigan.

THE UNWELCOME, UNEXPECTED GUEST

Enter COVID. The initial globe-wide lockdowns forced all but essential industries to temporarily shutter or limit their operations until the pandemic numbers eased. This caused severe workflow disruptions in Asia, where so many of our goods are manufactured. Even when those industries chugged back to life, their ability to work at full capacity was marred by backlogs across the supply chain, especially at ports and airports. They were also working with workforces reduced by illness, border closures and COVID mandates (mandatory quarantine periods, school and daycare closures, absenteeism), all while implementing workplace mandates such as PPE procedures and social distancing into their workflow. Soon, an excess of freight piled up in transportation hubs, further delaying shipping times, and there simply weren’t enough workers to deal with the congestion.

The massive white-collar shift to working from home plus the enforced isolation have only added to the stresses on the supply chain.“More people are ordering their goods online,” says Claudia Dessanti, Senior Manager, Policy, at the Ontario Chamber of Commerce and the co-author of the Ontario Chamber of Commerce’s 2022 Ontario Economic Report. “Consumers are making lots of smaller orders and ordering everything separately because it’s convenient. But that contributes to traffic congestion and the backlogs we’re already seeing at warehouses.”

“Manufacturers and retail outlets are also making larger orders and hoarding goods in anticipation of future delays.”

MIKE HEWITT, QUINTE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION

If that weren’t complicated enough, the pandemic was just the first in a series of crises that has slowed key components of the global supply chain to a crawl. In the summer of 2021, a freighter broke down in the Suez Canal, causing a massive backup of ships in the vital transportation hub. The British Columbia floods in the fall of 2021 led to the closing of ports along the coast, as did extreme weather events, especially wildfires, in California and Asia. At one point in the fall of 2021, a record 100+ ships waited, in some cases for months, to be unloaded in Los Angeles’s two major ports. Global economic production has been rocked by labour disputes, many triggered by COVID restrictions and mandatory vaccination policies. There was also a series of rolling blackouts as China’s manufacturers struggled to catch up to demand.

FROM GLOBAL CRISIS TO LOCAL CALAMITY

What does that look like on the ground here in southeastern Ontario? Mike Hewitt, manufacturing resource centre coordinator at the Quinte Economic Development Commission, explains that the local manufacturing industry, which contributes $6 billion to the region’s $12 billion dollar economy, has had to learn on the fly. “Manufacturers have had to adjust to lead times for raw materials coming in, to labour shortages, to shipping delays and product shortages, challenges which they have no control over.” Manufacturers and retail outlets are also making larger orders and hoarding goods in anticipation of future delays. “If you can get a shipment of parts from a manufacturer, you’re now going to order double what you’d usually order.”

Hewitt says this has revealed a major flaw in the popular Just in Time inventory management strategy, a system that cuts overhead costs and enables workflow efficiencies by reducing the amount of stock and raw materials the company keeps on hand. “Holding onto inventory and warehouse space that you’re not using right away is considered lost money,” he explains. “It’s money you can do other things with. But Just in Time requires everything to run smoothly across the entire global supply chain.” Hewitt also points out that Canada has long suffered from a shortage of truckers, a problem that will only get worse as more drivers reach retirement age.

For Christine DenOuden, the owner and designer of Kleur Design and Kleur Furniture & Décor in Bloomfield, COVID and supply chain complications negatively impacted business before it even opened its doors. “We had planned to open our storefront in May of 2020,” says DenOuden, “so we ordered all of our product in March 2020. We ended up sitting on $80,000 worth of furniture for six months before we were actually able to open our retail space to the public in October.”

Shortly after the store opened, the furniture and supply manufacturers DenOuden’s businesses rely upon fell so far behind on orders that they stopped updating retailers about timelines for new inventory. “Some timelines jumped from eight weeks to 20 weeks!” she says. COVID restrictions also forced organizers to cancel trade shows, making it difficult to source and assess new product. “It’s almost impossible to do your due diligence on a brand without going to a trade show and meeting the people, seeing their products, establishing the relationship.” For DenOuden, the biggest challenge has been managing customer expectations. While most have been patient and understanding, “as we move into year three, shipping and delays are getting worse. Unfortunately some customers assume that because restrictions are easing, delays should be ending.”

Alex Foster, the owner of Glengarry Construction & Design in Maxville, describes a series of “ebbs and flows” regarding the availability and pricing of raw materials like lumber, gravel and appliances. “The most frustrating and time consuming shortages seem to be random,” he says. “For instance, while most appliances will be available, you might have to wait 10 to 12 months for a specific dishwasher or fridge. The curbside safety measures that the hardware stores put in place were probably the worst of it; there are quite a few things that you miss on large orders when you’re sitting in your truck and calling it in rather than walking the aisles of a store.”

THE RICE KRISPIE SOLUTION

All the business owners contacted by Watershed report that the unprecedented challenges of the supply chain crisis have forced them to rethink some of the ways they do business. Michelle Laframboise, owner of ClearWater Design Canoes & Kayaks in Picton, says that her company has started ordering parts and raw materials in larger quantities, often months in advance. She’s also had to discontinue or substitute other products “because their costs have become too high to offer at an acceptable retail price.” Again, the biggest challenge is often managing customer expectations and disappointments.

In Campbellford, Michael Sharpe of Sharpe’s Food Market says that his team took an aggressively proactive approach to the supply chain failures right from the start. When essential products like toilet paper, flour and breakfast cereals disappeared from shelves because of panic buying, supplier shortages and shipment delays, Sharpe posted live Facebook and Instagram updates to keep customers informed. “We didn’t want people coming all the way to the store and not finding what they needed,” he says. He also posted updates on items that became available after long absences. “We got a shipment of Rice Krispies last Christmas Eve. Within an hour, the store was flooded with customers.”

When essential products like toilet paper, flour and breakfast cereals disappeared from his grocery shelves, Sharpe posted live Facebook and Instagram updates to keep customers informed.

Because Sharpe’s is an independent store, they can order from several different suppliers to make up for shortfalls: “If one supplier is short, we can phone another and maybe get a different brand.” But there’s only so much Sharpe and his team can do. Two years into the crisis, they are still facing delivery shortages of up to 40 percent. “I’ve heard from truckers that there is stock sitting in warehouses with no one to load it onto trucks,” he says. “The product is there: we just can’t access it.”

SIMPLE SOLUTIONS EASE THE STRESS

Scott Wentworth of Wentworth Landscape and Design in Picton confirms what other business owners are saying: adjusting to a constantly evolving crisis has been extraordinarily difficult. And according to Pat Campbell of Supply Chain Canada, the crisis will not necessarily end when the remaining COVID restrictions are lifted. “It’s impossible to pinpoint [a return to normal], but we anticipate it will take approximately six months to a year before the supply chain works its way through the backlog.” He also says that the weaknesses revealed by COVID are not going away. “There is no silver bullet to this problem: it is the result of a number of complex challenges that have compounded on one another.”

Business and government leaders are taking the problem seriously. The federal government recently hosted a Canadian Supply Chain Summit to discuss strategies to help strengthen the fragile supply chain. The Ontario Chamber of Commerce recommends changing some immigration policies to help fill holes in the labour market. “It would help to bring in immigrants specifically for areas in which there are labour shortages and retirements, especially truck drivers and childcare workers,” Claudia Dessanti says. “And for people who are starting their careers or changing careers, we should be promoting those jobs as a viable path. That starts with educating people about the benefits of those careers.” She stresses that there are many benefits to the hyper – connected global economy, but “strengthening our domestic manufacturing capacity and making sure that critical supplies can be manufactured closer to home should be part of the solution to the ongoing crisis.”

Keenan Sprague of Sprague Foods agrees: “Since the end of the Second World War, we’ve built a global system of trade and Just in Time logistics that maximizes efficiencies and drives prices down. However, the pandemic has shown that our supply chains were not built for resilience.”

Luckily for us, resilience may be lacking in the global supply chain but not in the local businesses that provide the economic backbone of the region. Scott Wentworth says that the troubles of the last two years are just another challenge in the life of a local business owner. “A crisis can really sharpen your ability to respond in the right way. It can bring out the best in us and sometimes even make for a better customer experience all around.”

Story by:

James Grainger

Illustration by:

Charles Bongers