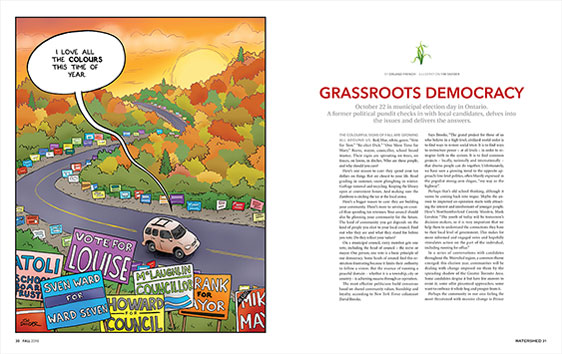

October 22 is municipal election day in Ontario. A former political pundit checks in with local candidates, delves into the issues and delivers the answers.

THE COLOURFUL SIGNS OF FALL ARE GROWING ALL AROUND US. Red, blue, white, green. “Vote for Tom.” “Re-elect Dick.” “One More Time for Mary.” Reeve, mayor councillor, school board trustee. Their signs are sprouting on trees, on fences, on lawns and in ditches. Who are these people and why should you care?

Here’s one reason to care: they spend your tax dollars on things that are closest to your life. Road grading in summer, snow ploughing in winter. Garbage removal and recycling. Keeping the library open at convenient hours. And making sure the Zamboni is circling the ice at the local arena. Here’s a bigger reason to care: they are building your community. There’s more to serving on council than spending tax revenues. Your council should also be planning your community for the future. The kind of community you get depends on the kind of people you elect to your local council. Find out who they are and what they stand for before you vote. Do they reflect your values?

On a municipal council, every member gets one vote, including the head of council – the reeve or mayor. One person, one vote is a basic principle of our democracy. Some heads of council find this restriction frustrating because it limits their authority to follow a vision. But the essence of running a peaceful domain – whether it is a township, city or country – is achieving success through co-operation. The most effective politicians build consensus based on shared community values, friendship and loyalty, according to New York Times columnist David Brooks.

Says Brooks, “The grand project for those of us who believe in a high-level, civilized world order is to find ways to restore social trust. It is to find ways to restructure power – at all levels – in order to reinspire faith in the system. It is to find common projects – locally, nationally and internationally – that diverse people can do together. Unfortunately, we have seen a growing trend to the opposite approach: low-level politics, often bluntly expressed in the populist strong-arm slogan, “my way or the highway”.

Perhaps that’s old-school thinking, although it seems be coming back into vogue. Maybe the answer to improved co-operation starts with attracting the interest and involvement of younger people. Here’s Northumberland County Warden, Mark Lovshin: “The youth of today will be tomorrow’s decision-makers, so it is very important that we help them to understand the connections they have to their local level of government. This makes for more informed and engaged votes and hopefully stimulates action on the part of the individual, including running for office.”

In a series of conversations with candidates throughout the Watershed region, a common theme emerged: this election year, communities will be dealing with change imposed on them by the spreading shadow of the Greater Toronto Area. Some candidates despise it but have few answers to resist it; some offer piecemeal approaches; some want to embrace it whole hog and prosper from it.

Perhaps the community in our area feeling the most threatened with massive change is Prince Edward County. This once quaint and quiet municipality is struggling to contain and control its new recreational community identity. Now the darling of wine connoisseurs and summer sun-seekers from the Big Cities, the County is at risk of losing its image as a slow-shufflin’ idyllic country retreat – the very thing that drew tourists in the first place. Traffic crawls in Picton; housing prices are rising out of sight and locals may soon find themselves priced out of their homeland. In the summer, its population swells into the hundreds of thousands. In effect, it is little more than a giant rural township with a lot of visitors.

The concerns of all three candidates for mayor – Richard Whiten, Dianne O’Brien and Steve Ferguson – reflect the struggle to retain a traditional sense of the community. Richard Whiten, in his first run at politics, laments the economic forces that are ripping his community away from its roots. “We’re losing our sense of place. We work hard to preserve our beauty and our history but we don’t do much to keep our people here. Nobody can afford to stay. My kids won’t be able to stay here.”

Dianne O’Brien, one of the three candidates for mayor, worries about the loss of the rural nature. With the closing of schools, crossroad general stores, and community churches, the economic heart of the County has concentrated in Picton, Bloomfield and Wellington. She wants to do what she can to reduce red tape to save local businesses.

Steve Ferguson sees the County as “a community of communities”. He’s an ex-Torontonian who stumbled into the County by accident and immediately fell in love with it. “The proximity of Toronto is both a blessing and a curse,” he says, as one who has settled in the County and loves it the way it is. “We’re trying to retain the neighbourhoods that have been created over decades, even centuries. We have significant historical values: we have built heritage, we have landscape heritage and we have an agricultural heritage. There is a very delicate balance among them.”

Outsiders bring new ideas to their adopted hometowns but are often a thorn in the side of local councils. Turning a deaf ear to new ideas will not help build that “social trust” that Brooks says is essential to developing a diverse society.

There is no question that all municipalities have to address this issue. But if the town of Cobourg is any indication, there is change on the horizon. The town is trying to build social trust through an improved website, live streaming of council meetings, more open houses and more information sessions to overcome feelings that decisions are made by small groups behind closed doors.

Cobourg Mayor Gil Brocanier is handing over the reins to acclaimed mayoral candidate John Henderson, who will have to navigate his council through some rough issues – marina expansion, development pressures, and the need to grow the commercial base in town. Amongst the slate of newcomers who are vying for a spot on council, are two women who hope to bring extensive outside experience and a younger outlook to the table. Nicole Beatty, a fund raising executive and Emily Chorley, a community organizer with a specific interest in vulnerable families, represent two of the 38 females in a field of 182 candidates – from Port Hope to Prince Edward County – standing for election, nowhere near a 50:50 female to male ratio but reflective of the breakdown across the country reported by the Federation of Canadian Municipalities in 2011.

In Brighton, Councillor Brian Ostrander is taking on incumbent Mayor Mark Walas on the need for the town to get organized. He says the town should be focusing on “Planning, planning and planning. Most of the conundrums that Brighton finds itself in today are the result of poor or no planning. We need to bring a team approach back to our municipality that includes consultation with ratepayers and stakeholder groups.” Walas doesn’t welcome the criticism. He has been quoted as saying that “Brighton doesn’t need a new mayor, what Brighton needs is a new council.”

New technologies enter into the realm of change as well. Ostrander, author of a book titled Community Matters, says, “We live in an era of instant communication where we can have ongoing dialogue with ratepayers and stakeholders.”

And Port Hope is one of the municipalities embracing the culture of the instant society by holding a paperless vote. Citizens can vote electronically over the telephone or the internet. There will be no paper ballot, and voters will have a chance to make their decision up to two weeks ahead of Election Day. It’s the town’s way of keeping up with their younger generations. But it’s not without controversy.

Terry Hickey is running against Port Hope’s incumbent mayor, Bob Sanderson. Whoever wins the race will have to face the ongoing issues of the low level radioactive waste cleanup, the restoration of the waterfront, and they will also have to balance the interests of two distinct groups within the community – one of which dismisses the importance of heritage within the town and the other of which feels that the town’s heritage should be preserved at all costs.

Change of leadership is the talk in Belleville, where voters are facing a strong four-way race for mayor (incumbent Taso Christopher, Councillor Mitch Panciuk, Councillor Egerton Boyce, perpetual politician Jodie Jenkins). The city is completing a string of expensive projects – police station, fire hall, casino, main street overhaul, and a renovated sports arena to accommodate a professional hockey team. Where does the city go from here? That’s the challenge that attracts people like Ryan Williams, chairman of QuinteVation and executive vice-president of Williams Hotels.

Williams, a front-runner for one of six council seats, is pushing an agenda of collaboration and cooperation with Belleville’s neighbours to bring prosperity to the whole Quinte region. He talks of fostering an innovative city. He says Belleville’s rescent accomplishments have set the table for “a city and region primed for greatness.”

Next door in Quinte West, Councillor Duncan Armstrong is challenging incumbent mayor, Jim Harrison, with a similar shake-’em-up approach. Affordable housing – reasonably priced for young families – is a major challenge, as it is anywhere in the Quinte area. CFB Trenton and Loyalist College suck up a tremendous quantity of available housing and the rental market is practically non-existent.

Transportation is also a major issue because there is no transit link between Quinte West, Belleville or Loyalist College in the city’s west end.

Like Quinte West, better known to the rest of the world as Trenton, the town of Trent Hills is still wrestling with a populist name change foisted on it by municipal amalgamations. Trent Hills sounds like an exclusive housing development with pop-up rural mansions but it is actually three long-established heritage communities in one: Campbellford, Hastings and Warkworth. “A vibrant area,” it describes itself on its website. “Flourishing with a microbrewery, artisans, professionals, tourism operators, organic farmers, unique retailers, trades people, landscape designers, wellness practitioners, manufacturers, and world-class musicians.” The town slogan beckons, “Come for a visit. Stay for a lifestyle.”

This is clearly an attractive form of community that Trent Hills is pursuing – the kind you’d like to live in. Trouble is, its enterpreneurs and professionals are at a disadvantage because Trent Hills is off the beaten tracks of Highways 401 and 7. Therefore, more flag-waving is required. Two candidates, Susan Fedorka and Bob Crate, are running for the mayor’s office, both of them offering ideas to attract more residents, more tourists and more vacation business to Trent Hills.

These are some of the communities-in-progress of Watershed Country. They have different goals, different desires and different issues. One thing they have in common: they are being built, as they have been for generations, by the people who live there. You could be part of that process.

Nomination deadlines have passed, so it’s too late to run for office this year. But there’s a short cut to being part of the action. You can get your foot in the door by volunteering to be a citizen on an advisory board or committee. Look for ads in your local weekly paper or on the municipal website. Pick up an application form at the town hall and state your preference. Library board. Police services board. Heritage committee. Parks and recreation. Get on a committee. First thing you know, you’ll be hooked.

In four years you could have your very own election sign on your lawn. “Vote for me! Help me help you build our community.

<

Story by:

Orland French

Illustration by:

Tim Snyder