The rivers and creeks that flow down our varied watersheds have modest beginnings in a network of headwater streams that, in some cases, appear to magically gurgle out of nowhere.

It’s a familiar landscape along the oak ridges moraine: a windswept hilltop that drops down to a mixed forest of Scots pine, black locust, and tall white pine, across an abandoned pasture bordered by young hardwood bush to a valley where the light reflects red-purple in the permanent shade of a cedar stand. It’s a place of fern, stones and cool dark shadows even in the sun and heat of summer. If you are inclined to search for hobbits and fairies, this is where you might look. This shady spot, where strands of ice cold water mingle in the green moss to form rivulets and weave themselves into the life waters of Northumberland, shelters one of the springs that will eventually become part of the Ganaraska River.

The Oak Ridges Moraine hides hundreds of such treasure spots along its 160 kilometres of ancient glacial hills: quiet glades where springs issue from the earth to gather as the source waters for the streams and rivers flowing south to Lake Ontario and north into Rice Lake. Although it is perhaps thought of as a geological feature north of the GTA, the Oak Ridges Moraine is very much a part of Northumberland County. Approaching from the northwest, the moraine veers south of Rice Lake before reaching the Trent River, making its presence felt with a unique and priceless ecosystem.

This natural rain barrel, which provides drinking water for thousands of Ontario residents, was manifested some 13,000 years ago as two great glaciers of the last Ice Age gradually began to melt. Sand, silt, soil and rocks fell from the ice to the bottom of the waters, collecting between the two great glacial lobes. What remained when the ice melted was a hilly ridge, topped by a highly porous sand summit that eagerly gathers rain and allows it to percolate down, much of it joining a vast aquifer under the moraine, but some of it hitting a layer of less permeable till soil – soil that doesn’t absorb it but propels it to the surface, where it emerges as rivulets of fresh water.

Such springs are a feature all along the moraine. For instance, just north of Cobourg, in a picturesque valley between two hills, we have the aptly named hamlet of Cold Springs, which features several places where the clear water flows straight out of the ground. Pioneer writer Catharine Parr Traill noted in her 1836 book The Backwoods of Canada: “Who knows but some century or two hence this spot may become a fashionable place of resort to drink the waters. A Canadian Bath or Cheltenham may spring up where now Nature revels in her wilderness of forest trees.”

Fast forward to the early 20th century and the aftermath of the great logging boom that cleared the forests of south and central Ontario for ships’ masts, square timbers, fuel, lumber and agriculture.

The moraine, with its summit of fine sands, proved particularly vulnerable to erosion as the forests were felled. Early farmers who tilled the clear-cut moraine hills enjoyed a few years of prosperity before they saw the thin soils blow away and wash downstream. Springs dried up, creeks which had once flowed year round became seasonal, and the water table dropped, with reports of well water declining by tens of feet.

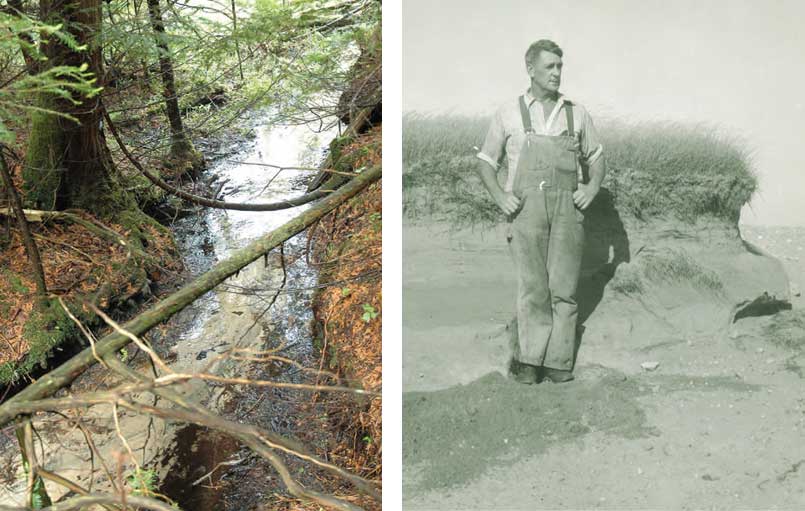

In the 1940s A.H. Richardson, a forestry engineer and a pioneer of conservation in Ontario, released his groundbreaking Ganaraska Watershed Report which provided graphic evidence of the devastation. Where water once flowed, and trees provided cooling shade and controlled erosion, was now a bleak landscape of dunes and dry gullies. The loss of forest cover in the uplands of rivers such as the Ganaraska meant high peak water levels during the spring melts, leading to periodic floods in Port Hope during the late 1800s and into the next century.

Early farmers who tilled the clear-cut moraine hills enjoyed a few years of prosperity before they saw the thin soils blow away and wash downstream.

Richardson looked back to atlases and maps of Ontario published in the mid to late 1800s to find that headwater streams had once extended much farther up the slope of the moraine, at a time before it was logged. “No one, who has lived in the wooded areas of Ontario and has watched the forest being cut down over large areas, will gainsay the fact that water supply in the springs has been changed.”

Wildlife communities suffered as the hills were stripped. Wrote Richardson in 1944: “Today Lake Ontario salmon and passenger pigeons are extinct; the sturgeon fishery at the mouth of the (Ganaraska) river is comparatively insignificant; bears are gone; beavers, deer and wolves are almost extinct locally; speckled trout, grouse and hares are greatly depleted.” A.H. Richardson’s work led the province to purchase and reforest thousands of acres of eroded Ganaraska farmland, benefiting not only ecology and reducing flooding but also helping a community that had hit an economic dead end. The purchase of marginal lands for reforestation provided impetus and opportunity for many to find better livelihoods than offered by their depleted farms.

Today these conservation lands, such as the 10,000-acre Ganaraska Forest and the 5,500-acre Northumberland Forest, form the core of a central Ontario ecosystem mapped out in the provincial Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan, which identifies areas where the aquifer is vulnerable to human impact and provides direction on appropriate land use and resource management.

The work initiated by A.H. Richardson is carried on by both government and private landowners who know the value of the Oak Ridges Moraine, its coldwater streams, their connection to healthy wildlife and human communities and the importance of maintaining natural systems.

The work of local government and private landowners to enhance and protect the moraine should provide some optimism, not to mention a few learning moments, for those who ponder the impact of human activity on our planet in a time some scientists have dubbed the “anthropocene,” a geologic era when our species has been the dominant force shaping the earth. Private owners have sought to protect the values of their land in the long term. Many have signed conservation easement agreements with land trusts to ensure the protection of their properties in perpetuity by binding future owners to continue stewardship of the land.

Going back to A.H. Richardson’s report seven decades later, we can say that the passenger pigeon will never return, but beaver have rebounded, bear are not unknown, and there are deer aplenty – some would say too many. The large tracts of unbroken forest on some parts of the moraine also provide vital habitat for many species of songbirds which are prone to predation in the fragmented woodlots that cover much of rural Ontario.

Any healthy environment is balanced. As well as rocks, forests and streams, the historical tall grass and oak savannah habitats on the Rice Lake Plains also form part of the moraine’s vista. Given the Indigenous name “lake of the burning plains,” these grasslands were once many times larger and were in danger of disappearing as the ground was becoming overgrown with invasive species. Today, thanks to a partnership that includes municipal governments, nature conservancy groups and the Alderville First Nation, the area is on the path to restoration and sustainable management.

There’s more good news in the streams and rivers.

Streambeds that appeared as dry gullies in photos from the 30s and 40s now flow with water year round. Groundwater sources have responded positively, both in quantity and quality. Clean, cold, resilient streams in turn help support a healthy fishery for trout and salmon which rely on the ability of colder water temperatures, originating in the moraine’s springs and maintained by tree cover, to retain the high levels of dissolved oxygen they need to survive. It’s not a stretch to say that fish grow from trees.

None of this comes to us without attention being paid. The provincial government appears to have moved its pro-development agenda into high gear and is undercutting the roles played by our conservation authorities – roles that are critical to the protection and maintenance of the region’s ecosystems. The springs that bubble up through the porous earth on the Oak Ridges Moraine are not just features on a hike or photos on a web page, they are part of a synergy of earth, air and water working to create the watershed that sustains us. These abundant, clean water sources and the diverse habitats are essential to the region’s health, if not its survival; few people who have walked through the area can doubt its usefulness as well as its beauty. Paving this paradise is simply not an option. The fragile magic of the Oak Ridges Moraine and its springs has been with us since the last Ice Age. It is worth holding onto a while longer.

Story by:

Norm Wagenaar