How a young Irish immigrant taught himself to become a teacher and one of Canada’s most prominent botanists. From his wide-ranging field trips across Eastern Ontario and Canada, John Macoun of Belleville collected more than 100,000 plant samples

FILBERT NUTS INTRODUCED John Macoun to nature in county down, Ireland. But it was in eastern Ontario that he developed an immense appetite for collecting, naming and cataloguing Canadian flora. This celebrated self-taught botanist wrote in his autobiography, “When I was quite a small boy my uncle took me into the orchard and showed me a row of filbert trees and pointed to the aments, or barren flowers, hanging on the branches of the naked trees and said to me: “Jock, these that you see here will all fall off and in the autumn it is on these trees we get the nuts that we use at Christmas time.”

As if by a miracle, Macoun discovered the same species in Canada while splitting cedar rails one morning in May. He examined the bush closely and, many years later, remarked in his autobiography, “These were the first studies I made in botany.” In the mid-1800s Canada was still an unexplored land, botany-wise. Ireland’s plants may all have been named, but not Canada’s. About the same time, Catharine Parr Traill had been fascinated with the flora of Upper Canada. As had Elizabeth Simcoe, wife of Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe, in the 1700s. For immigrants from Europe, Canada was an unexplored natural garden.

At the age of 19, Macoun emigrated to Canada with his brother Frederick in 1850. They made their way to Belleville, intent on seeking out an uncle who had settled in Seymour Township. His first experience in Belleville was being offered “bitters” by a stranger. “He put a bottle before us and a cup and asked us to help ourselves and, behold, it was whiskey of a very unpleasant taste.” So unpleasant, apparently, that it earned a place in his autobiography.

He found his uncle living in a shanty, impecunious from attempting to live off the land. Nevertheless Macoun tried farming for half a dozen years before deciding it was not for him. He admitted he acted like a greenhorn most of the time. If there was a hard way to do anything, he found it. (Once he cleared a long laneway of snow in anticipation of the arrival of his uncle by sled, only to learn that the horses couldn’t draw the sleigh over bare ground.)

Turning his back on farming, he wanted to pursue a career as a teacher, learn what he could about botany, and make more money than in farming. He concluded that he could be a good teacher. His first teaching job paid him $14 a month, plus board.

From Seymour he went to Brighton to teach, and in his first year he collected 256 plants that he named. He brushed up on his grammar with a three day study of Kirkham’s Grammar where “I decided that I could pass for a school teacher without difficulty.” After he spent three weeks in school, he got his teaching certificate. The expectations of the school trustees were apparently not too high. Macoun was in his mid-20s when he got teaching jobs in Seymour and Brighton.

After attending Normal School in Toronto, where he received further training as a teacher, he transferred to Castleton where he spent 10 months teaching and studying botany. He came to be good friends of a Dr. Gould and spent early morning hours collecting plants on the Rice Lake Plains. In the fall he landed a job at No. 1 School in Belleville.

Macoun delighted in fieldwork and would examine anything unusual. He once found a flying squirrel in the stomach of a trout (presumably, unlike Jonah, quite dead). In fact, one of his faults was that he would spend his time pulling up flowers and grasses and not bothering to organize them as he went along. Fellow travellers became impatient with his constant collecting of grasses and other plants, and called him “The Hay-Man”.

His passion for botany was no longer a hobby. “My removal to Belleville was the real turning point of my life. Before the winter was over I had discovered I could hold my own with the best of teachers and stood well with the people. I then decided to devote all my spare time to natural history and as a commencement bought a few books.”

He soon didn’t trust the books. “When I learned from it (Goldsmith’s Natural History) that ants laid up corn for winter, I knew better.”

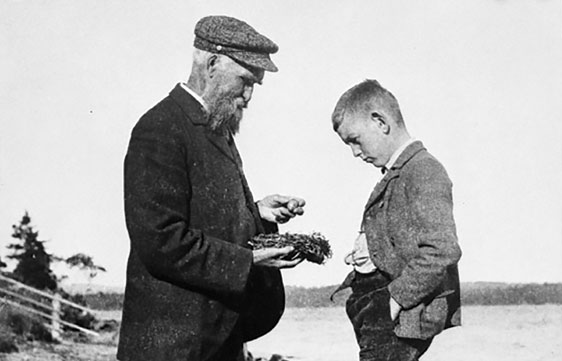

He struck up friendships with botanists such as Asa Gray, Sir William Jackson Hooker, George Lawson and Louis-Ovide Brunet. His enthusiasm and connections led to a higher level of teaching: professor of botany and geology at Albert College in Belleville. In 1862, at age 31, he married Ellen Terrill of Brighton. They raised two sons and three daughters; his eldest son James Melville Macoun became his lifelong assistant, while his younger son William Tyrrell Macoun became the Dominion Horticulturalist for Canada. Botany certainly ran in their veins.

And yet, for all his enthusiastic successes, he made a major mistake, unintentionally, by misreading the long-term climate of the Canadian prairies.

Between 1872 and 1881, Macoun worked with Sir Sandford Fleming to plot a route across the Prairies for the Canadian Pacific Railway, Canada’s first transcontinental rail route. He determined that a line through southern Saskatchewan would be the way to go. Thanks to several successive years of plentiful rain, this area was lush grassland when Macoun passed through.

But there had been a warning that it could be otherwise. The Palliser Expedition in the late 1850s, after four years of exploration in Western Canada, had concluded that the largest proportion of the Prairies was an extension of the Great American Desert. And that’s what it became during the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. Macoun’s Eden was an aberration. Palliser’s Triangle, as it came to be known, was generally almost as dry as a desert. The mis-assessment wasn’t really Macoun’s fault. Still, the error forever stained the otherwise impeccable record of Canada’s most enthusiastic and determined botanist.

Macoun’s reports from the West received close attention in Ottawa. In 1879 the government of Canada appointed him “explorer of the Northwest Territories”. Two years later he joined the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) as “Botanist to the Geological and Natural History Survey of Canada.” He moved to Ottawa and remained with the GSC for 31 years. He devoted his time to collecting and cataloguing Canadian flora and fauna, what he loved doing most of all. The National Herbarium of Canada in the Canadian Museum of Nature has more than 100,000 samples of his collection of plants.

Macoun died in 1920 in Sidney, British Columbia, and is buried in Beechwood Cemetery in Ottawa, next to Macoun’s Marsh.

A century after his death, John Macoun is receiving the attention he deserves. Next year, to mark the 100th anniversary of his death, the Hastings County Historical Society and the Quinte Field Naturalists Association plan to commemorate the botanist’s remarkable accomplishments on a plaque in the area. In 2018, the federal government erected a plaque in Macoun’s honour at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa.

Story by:

Orland French