Having issues with your internet? You’re not the only one. Follow the stories of four local business owners and how they adapt to the vagaries of rural internet service.

Julie Haché sits in her home office in Prince Edward County conducting an online business coaching session. Suddenly her client’s face disappears from the computer screen and the session ends. Julie’s internet connection has failed. Again.

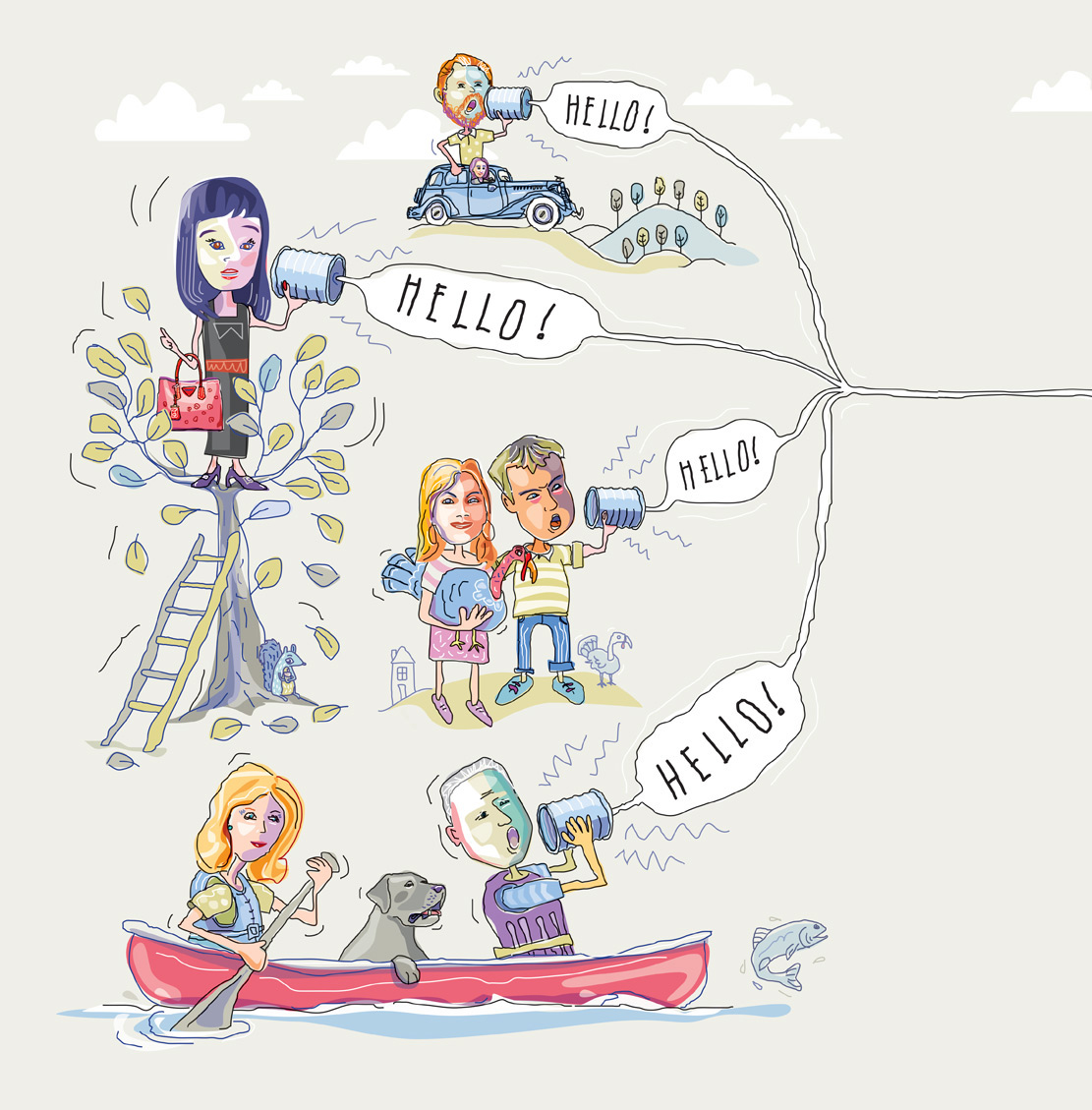

Julie’s situation is familiar to many people who use the internet in rural Ontario. It seems that everyone in the region has a story to tell. Whether it’s bad service from a provider, an unreliable signal, or a glacial download speed, internet in rural areas sparks lively conversations at social gatherings and fuels frustration at home. People speak of owning satellite dishes that spend the winter covered in ice and snow, unloved and unworking; of wandering around outside the house looking for a signal; of pooling money with neighbours to pay a premium for fibre optic cable on the street.

In the following pages we will meet four sets of people who are dealing with internet access as it is experienced in our region’s less-developed areas. There are humans connected to all those bits, bytes, and milliseconds, and these are some of their stories.

JULIE AND JAMES: MAKING IT WORK

Julie Haché and James MacAulay live on a broad stretch of property just outside Consecon in Prince Edward County. Their stunning home, all modular cubes and glass, is a nearly complete work-in-progress. Workers are putting the finishing touches on steps and floors. Everything seems sparkling new and clean. They have already opened a separate outbuilding as a B&B.

All that’s lacking in this idyllic setting is fast, reliable internet connectivity. Their internet comes from a line-of-sight tower not far away. On good days they have a download speed of 10 megabits per second (Mbps). But there aren’t that many good days. When there are too many users online or a tree branch swings between them and the tower, they can lose their connection.

“If it’s a little windy,” says Julie, “we don’t have internet.”

This situation is a show-stopper in the professional world Julie and James occupy. The young couple came from Toronto three years ago looking to change the pace of their lives, fell in love with the area, and began to build a house and a life. In the city they both worked as software developers for high-profile clients such as Shopify and Bitmaker Labs. They still write software, and Julie is a consultant and mentor to women and girls who work in high tech. Now that they live in the County, they plan to continue their careers. Julie is expanding her personal coaching business and meets with many of her clients online, which presents its own challenges.

“The service seems random,” Julie says. “It will be working fine and then cut out suddenly.” This leaves her clients stranded, cut off from their connection with her.

Julie and James are finding ways to work around the problem. Sometimes they go to a coffee shop in Picton for better connectivity. But you can’t hold a client meeting in a coffee shop, so coping has its limits. One work-around initiative has been to band together with others in their profession to form a collective of high-tech resources. Coworking, a popular business option in cities, is the concept of pooling temporary office space for those who need it. Julie and James are co-founders of County Coworking in Picton, a bricks and mortar establishment where people who need office space – including reliable high-speed internet – will be able to rent facilities to help them carry on business.

Working at home is more desirable, but a perfect online environment eludes them. It can be absolutely frustrating, says Julie. “I was a bit surprised at how remote it feels on the internet here.”

The surprise is real, as they live in a well-developed area, minutes away from a town. But it seems to them as if the neighbourhood has been overlooked in terms of internet.

“We’re coping,” says James. “We’re resourceful people and are making it work but it’s harder than it should be.”

DANA AND JAMES: A NEED FOR HIGH PERFORMANCE

Dana Sinclair and James Sleeth work in Toronto but get away to their farm outside Burnley, just west of Warkworth, at every opportunity. They would both love to spend more time there.

Over the years they have built new additions onto their nineteenth-century farmhouse to create a spectacular but comfortable living space. Their property now includes accommodations for guests as well as a separate gym. Still to come: adequate internet access. Dana is a renowned performance psychologist and a partner in Human Performance International, where James is also a partner and the managing director.

Dana’s career is truly international, spanning professional sports that include the NFL, NBA, NHL, Major League Baseball, and the Olympics.

One of her higher-profile clients is Canadian tennis star Bianca Andreescu.

Dana’s professional success points to the connectivity challenges she and James are facing as they try to transfer some of their business to Northumberland County.

“When I was on Facetime talking to Bianca,” she tells us, “I had to walk around the property trying to keep the signal.”

Their download speed vacillates between four and seven Mbps, not even close to optimal. They are also surrounded by Northumberland’s many hills, which often creates reception problems. A foggy day can make it even worse. If Dana needs better access she sometimes goes to a coffee shop in Port Hope. Email messages arrive sporadically: none show up for a while and then they all come at once (“like ketchup from a bottle,” as Dana puts it).

Some of her biggest problems occur when she is working at remote, time-sensitive events such as the NHL or NFL drafts. She needs to be online in real time all the time, with no interruptions or delays. Doing that at the farm is a real challenge, she says.

James and Dana are currently writing a book together about performance psychology, and their plan is to spend more time in Northumberland in the coming years. They hope the internet service will get better.

“You hear a lot of talk about the productivity of a nation,” James notes. “Something like the internet will play an important role in productivity everywhere in the country, not just the urban centres.”

JEANNE BEKER: FASHIONABLE CONNECTIONS

Jeanne Beker is a household name in the fashion world, having established herself as a media personality, editor-in-chief, author, and fashion entrepreneur. Her quarter-century association with Fashion Television made her famous around the world. These days she is as busy as ever, working as Style Editor for The Shopping Channel as well as hosting the series “Style Matters with Jeanne Beker.” Her work has garnered her many awards, including the Order of Canada.

Jeanne is also a proud Northumberland resident.

When she moved from Toronto to a romantic but remote stone farmhouse near Roseneath twenty years ago, she was at a time in her life when she needed solitude and rest from the rush of big-city life. Although she achieved the lifestyle change she was looking for, the trade-off was slower connectivity with the rest of the world. The available internet service was a dial-up connection – as it was in many rural areas until just a few years ago – with questionable reliability.

Phone service was also dodgy at times. “I found myself sitting outside just to get a signal,” she says of those early days, a position familiar to many rural users.

Nevertheless, like so many residents of Northumberland and Prince Edward Counties, she found ways to make her farmhouse location work.

Although she was living in the country, her daily assignments still included filing news stories, keeping up with the fashion world, and maintaining blogs and other social media. Internet connectivity was never a problem after those initial, early years, which made the choice to move to this peaceful locale, a considerable, yet positive decision.

In 2016, she and her partner bought a fine old house in Warkworth and she now enjoys all the advantages of Northumberland life as part of the vibrant community there.

ROD AND NANCY: ON TOP OF THE WORLD

On an orderly, picturesque property at the top of a hill north of Grafton, Rod and Nancy DeJong grow corn and raise turkeys and rarely worry about the internet anymore.

Rod and Nancy’s internet service provider is Airnet Wireless, a small family-owned company located in Centreton. The company’s founder, Carl Jeptha, has established relationships with farmers in the area and negotiated the use of many of their silos and grain elevators to locate the company’s wireless repeaters (components that relay the signal), providing better service to rural customers.

Rod and Nancy are two of the lucky ones who have Airnet’s repeaters on their elevators, making their internet connectivity about as good as it gets. It has been a godsend to them, revolutionizing their lives and becoming an essential component of their farming business. Rod uses an app on his smart phone to monitor and control all critical operations in his outbuildings. Such a thing would have been unthinkable even a dozen years ago.

“Our first internet was only a dial-up connection,” says Nancy. “I was only on the computer once a week.”

“You could make a coffee in the time it took for a page to load,” adds Rod.

The arrangement with Airnet is a win-win relationship. They started with one repeater about seven years ago and now the elevator is covered with them. The Airnet technicians come to their farm periodically and climb up when there is maintenance work to be done. “Sometimes we send them up with a grease gun and get them to grease our bearings for us,” says Rod.

They’re not using the internet for their TV reception, so the couple still have an old-fashioned antenna, something that’s not as unusual or retro as it sounds. “Lots of people are looking for them these days,” laughs Nancy. “If you can get it high enough you can get a good line-of-sight signal.”

Rod and Nancy are Northumberland natives to the roots and have invested many years to reach this desirable point in their lives. Their beautiful modern house and spectacular outbuildings are a testament to years of hard work. And their foresight in allowing wireless repeaters to live on top of their grain elevators has kept them connected and in business.

THE STORY FROM HERE

The stories in this article describe very different people and situations. Some are surviving, some are thriving, and some are coping. The common thread is that internet access in more remote areas is not what it could be, and certainly not equal to what is enjoyed in cities or even towns.

Should it be? Some city dwellers might argue that people living away from major urban centres have to be prepared to compromise: peace and natural beauty in exchange for reliable Netflix. For her part, Dana Sinclair says she would never trade the quiet and solitude of country living just for faster internet. But the reality of doing business is always present.

As we have seen, not everyone who moves to the country from Toronto is a retiree who will use the internet occasionally and casually. More and more newcomers, like Julie Haché and James MacAulay, or Dana Sinclair and James Sleeth, plan to continue in the workforce for many more years. A media star like Jeanne Beker simply could not function personally or professionally without reliable, high-speed access. And long-time residents like Nancy and Rod DeJong rely on connectivity to keep their business alive. It can be said that the internet improves the quality of life for almost everyone, but there’s no doubt it is a critical component of business. And for many, that is a quality of life.

Some city dwellers might argue that people living away from major urban centres have to be prepared to compromise: peace and natural beauty in exchange for reliable Netflix.

WHAT’S IN THE FUTURE?

The CRTC has mandated that all Canadians should have access to internet service that provides a download speed of 50 Mbps and an upload speed of 10 Mbps. To many residents of rural Ontario this is just a dream. Some are getting by with less than a tenth of that.

Even as bandwidth expands and speeds increase in the cities, rural availability is stalled. Bell Canada announced recently that it was scaling back plans to expand its rural wireless service – which might have helped alleviate the lack of physical infrastructure – in response to a CRTC decision that lowered allowable fees.

For the time being, internet in rural communities will most likely be provided by fixed wireless services, which means more line-of-sight towers will be built. This technology is not ideal for anyone who lives in a hilly region, as so many do in Northumberland. And as we’ve seen, it doesn’t take a hill to disrupt a wireless signal: sometimes a strong wind or a bad weather day can also do it.

It will get better as technology evolves, but more slowly than some business people would like. The hope is that the improvements will arrive in time to be of help not only to those who have lived here all their lives, but also to those who hope to come here to start new ones.

The Need for Speed in Rural Ontario

WHAT IS BROADBAND ANYWAY?

In a recent digital strategy survey conducted by Northumberland County, residents said that access to broadband service was their number one concern. So, what does “broadband” mean?

Broadband internet is basically any type of transmission that is not dial-up. And although dial-up internet is not as extinct as you might think it is (or should be), most people in Northumberland County have some type of broadband access.

Put very simply, there are two ways to get online: via a cable or through the air. Cable is delivered through a line to your house, for example a phone line or fibre optics. Satellite and fixed wireless services (what we think of as cell towers) are received without a physical connection.

Two main factors that affect your internet speed are bandwidth and latency.

Bandwidth is the amount of data that can be transferred at one time, usually measured in megabits per second (Mbps). To use a common comparison, you would expect Highway 401 to carry more traffic at one time than Highway 2.

Latency is the speed at which the data travels, or the delay caused by how long it takes the data to move between its source and you. You could think of it as the response time after you press ENTER. Latency is usually measured in milliseconds (ms). A high rate means a slower response.

Think of a hundred cars travelling at once between Port Hope and Brighton. Which highway provides faster results?

Generally, satellites have a high latency rate (bad) and a high download speed (good) and cable has a low latency rate (good) and a so-so download speed. If you want to see this at home, you can test the upload and download speeds to your active server as well as your latency rate by using an online utility such as Ookla (speedtest.net).

SO WHAT IS BEING DONE?

According to the CRTC, the number of rural addresses with internet access at a speed of 50 Mbps (download) and 10 Mbps (upload) is less than half that of the national average. The federal and provincial governments have said that they are working to close the gap.

In 2019, the Government of Canada launched a national strategy to improve access to broadband technology, that included a $1.7 billion Universal Broadband Fund. This could be a major boost for rural communities – provided it can be maintained by a minority government.

The Province of Ontario announced last summer it is investing $315 million over the next 5 years to focus on expanded access for “unserved and underserved communities.” This will reportedly translate to improved service for 220,000 Ontario households and businesses.

Whether these initiatives will mean faster internet speeds in homes and offices in Northumberland, Quinte or Prince Edward County anytime soon is yet to be seen.

The reality is that the average rural population density of Eastern Ontario is well below the profit threshold that any private service provider would consider for broadband access. This means that private-governmental collaboration is essential for any kind of meaningful progress.

One group that is operating at this level is the Eastern Ontario Regional Network (EORN), a not-for-profit organization that aims to enhance quality of access through public-private partnerships with internet stakeholders.

EORN’s Director of Communications, Lisa Severson, recently spoke of their new project to enhance the cell network in Eastern Ontario and ultimately ensure cell service on 99% of all roads in the region. Construction to put new towers and equipment in place needs only to clear the final bureaucratic hurdles. “We hope to have shovels in the ground by next winter,” says Ms. Severson.

However, Ms. Severson cautions that dedicated wired access to internet – via cable or fibre – across rural Eastern Ontario is unlikely to happen anytime soon. The price tag for putting such an infrastructure in place could be half a billion dollars, and this doesn’t include ongoing operations or maintenance. The future is more likely a fixed wireless system – more line-of-sight towers. But this too will take time and money.

So… progress is happening, but like rural internet itself, the speed is questionable. For the rural households and businesses that can’t yet access a robust and reliable high-speed connection, the nearly unlimited potential of the internet still remains out of reach.

Story by:

Chris Cameron

Illustration by:

Charles Bongers