The first two decades of this century have been quite a journey for the world and for our part of it. Watershed has been there every step of the way.

How long is twenty years? If you’re a glacier, it’s barely enough time to shove a few rocks around. If you’re a parent raising kids, it’s literally a lifetime.

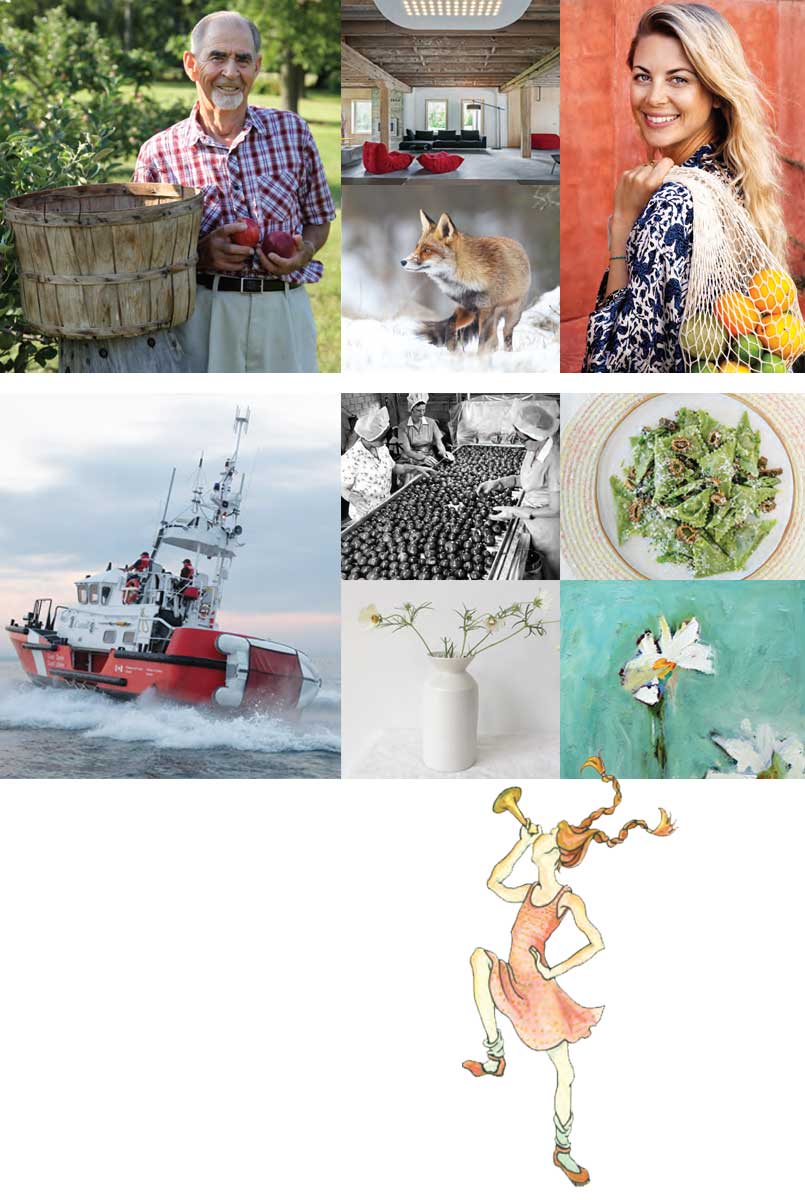

And what if you’re conceiving, organizing, writing, editing, formatting, printing and distributing 25,000 copies of a magazine over 3,500 square kilometres of Northumberland, Quinte, and Prince Edward County? And repeating the process four times a year for each of those twenty years? The easy math belies the incredible work involved: eighty issues mean countless words assembled by top-notch writers; thousands of pages of beautiful art and photography; literally tons of magazines loaded on and off trucks and picked up from stores, libraries and other sites across Watershed country by thousands of readers. And each issue has to be perfect, from front cover to back page. But no pressure, right?

In the first issue of Watershed, twenty years ago this summer, founder and publisher Jane Kelly wrote of her vision for “a unique magazine that reflects the richness of the region.” This dream has inspired every one of the past 80 issues (81 if you count this one).

If all those issues could talk, what stories they could tell. Wait … they do talk. From art galleries to wine cellars, from barrel-making to water-witching, the pages of this magazine have told their share of stories in twenty years. Every issue has documented the changes in Watershed country as well as those things that remain constant. And a twentieth anniversary is the perfect time to reflect on both.

BUSINESS IS GROWING

Throughout the twentieth century, a lot of the land around us was given over to family fruit farms. An article in the Fall 2003 issue of Watershed wondered about the future of these farms as residential and industrial development advanced from the west. In fact, many orchards still wend their way down to Lake Ontario, and apple production has held its own in recent years, while honey bee farms have doubled in number. But that’s not all that’s been growing. Prince Edward County was once known as the “Garden County of Canada.” As the 21st century dawned, County fruit and vegetable farmers were quietly joined by some visionary and intrepid grape growers.

It’s difficult to imagine that before 2000 there was hardly any wine industry in Prince Edward County. In just twenty years, though, this one-time military outpost has become a destination for wine lovers and has spearheaded a booming tourist industry.

The vinifera grape was grown in the County in the 1980s and 90s, but it was not until 2001 that the first winery in the region, Waupoos Estates Winery, opened for business. Watershed reported on the “promises and challenges of the budding wine region” in 2003. That year, the County was named a wine-growing region, and it was awarded the coveted VQA designation in 2007. Since then, over 40 commercial wineries and countless vineyards have sprung up, forming part of the Taste Trail, which attracts tourists to sample the best of the region’s food and wine. Among the pioneers of the now famous trail were fellow Watersheders Jane Kelly, Meg Botha and Stephanie Campbell, who downed countless glasses of County wine in the name of tourism research. It was a tough job, but someone had to do it…

Innovation in agriculture has grown faster than corn in July over the past two decades. Many farm-fresh ideas are now developed at the Ontario Agri- Food Venture Centre (OAFVC), a project led by Northumberland County Economic Development. As described in the Fall 2015 issue, OAFVC is a small-business incubator in Colborne with a mission to provide space, equipment and infrastructure (including a freezer that can chill half a ton of produce in an hour!) for those who want to develop new food products and sustainable ways of producing them. Farmers and food entrepreneurs have access to safe, clean, food manufacturing spaces and qualified production support staff.

On a smaller but equally critical level, all but disappeared by 2000 were the region’s beloved bluebirds, once a familiar presence along our fencerows. After suffering the destruction of much of their habitat, they have been making a comeback in this century, thanks in part to the assistance of amateur birdhouse builders. It’s possible that some of those builders learned their craft from the plans published in the Spring 2003 issue.

WELCOMING ARTS AND ARTISTS

From Farley Mowat to Shani Mootoo, from Marie Dressler to Sonja Smits, art and artists have always found a home in our part of the province, and their numbers have grown steadily in the past two decades. Northumberland’s Spirit of the Hills was formed in 1999 to provide nourishment and support for groups of writers, artisans and visual artists (their 20th anniversary was reported in the Fall 2019 issue). Even though in-person meetings have been impossible recently, the groups still meet online and sponsor projects, exhibitions, and even contests.

Art and artists have always found a home in Watershed country, and their numbers are growing.

To complement established institutions like the Art Gallery of Northumberland, smaller venues such as the Arts Heritage Centre of Warkworth (opened in 2015 and fondly called the AH! Centre) have sprung up. In response to the broadening artistic demographic in the County, showplaces like the Oeno Gallery appeared. Opened in 2004, the gallery moved to the Huff Estates Winery in 2009, acquiring a sculpture garden two years later, which was described in Watershed ’s Summer 2011 issue. The gallery is a destination for collectors, art consultants and designers, and hosts over 10,000 visitors a year in non-COVID times.

Independent bookstores are a prominent feature of nearly every town throughout our region. Our reading habits have shifted in the past two decades, although not as much as people might have predicted. The biggest change, of course, has been the move to digital platforms like Kobo, Kindle, or audiobooks. Despite this trend, Kathryn Corbett, owner of Lighthouse Books in Brighton, notes that there is a still a lot of demand for books in printed format. “Digital devices have not wiped out ‘real books,’” she says. Statistics bear this out. Although audiobooks have grown in popularity since they were introduced, people who listen to them exclusively still make up only 11% of all readers, according to a 2020 study by BookNet Canada. And many of those listeners also own the original printed book.

An artistic treasure of Northumberland and indeed Canada, what’s now called the Westben Centre for Connection and Creativity through Music began in 2000 with a gala Canada Day concert in their barn. By the 2019 season Westben had grown to present over 80 events in venues around Northumberland. As COVID ravaged live performing arts, Westben fought back with novel presentation approaches – podcasts, digital concerts, and this summer, new outdoor venues for live but safely distanced performances.

One life-long Northumberland resident has seen a great deal of change in his seven decades, but he believes that the best parts of his hometown are the things that never change.

A lot of Westben’s success rests with its remarkable community involvement. From taking tickets to singing in the chorus, over 200 local volunteers now contribute to Westben’s operations. Head volunteer coordinator Sandy Robertson has been there from the start and has seen it all. “Westben has expanded incredibly,” in twenty years, she says. She credits founders Donna Bennett and Brian Finley, whose vision widened the scope of the traditional concert to make good music accessible to all.

The Spring 2017 issue congratulated Donna and Brian on being named to the Order of Canada for their work connecting world-class music with the community – and connecting the community with the music.

SPEAKING OF CONNECTIONS

Although many of us still yearn for fast reliable internet and good cell service, twenty years ago these didn’t exist at all in many parts of Watershed country. An ad in the summer 2001 issue promised three types of internet access: dial up, DSL, and high-speed wireless. That last one, however, was asterisked as “may not be available in all areas” – something that has not changed much since then.

But success stories surface. There are fewer dead spots for our phones, and the Eastern Ontario Regional Network (EORN) is spearheading a massive project aimed at 99% coverage by 2025. Cell towers were a rare sight in 2000; now it’s hard to miss them. And although rural areas will never enjoy the ubiquitous fibre cabling that our city cousins do, line-of-sight access has improved for many people.

The Spring 2020 issue told the story of Rod and Nancy DeJong, whose first internet connection on their farm north of Grafton was dial-up. You could make coffee in the time it took for a page to load on his computer, Rod told us. Today they run their entire farming operation from an app on their cell phones.

The improvements are crucial to our future. For instance, it’s impossible to imagine what our community connectedness would have been like if COVID had struck twenty years ago. Brand new to most of us in 2020, digital video platforms such as Zoom have become a part of everyday life, and they will remain with us after the pandemic is history.

A LEGACY OF GROWTH AND SETTLEMENT

While many things were changing around us, we were also learning how to conserve the past. Downtowns have managed to beautify their streetscapes while maintaining the heritage architecture that makes them so attractive. Think of the success stories of Port Hope’s Cameco Capitol Arts Centre or Cobourg’s main street, including Victoria Hall. Luckily for our surroundings, municipal governments learned early on that slowing development to preserve architectural heritage is a desirable thing, not an impediment to what used to be called progress. “We must be wary of the slow chipping away of the foundations of our past,” Jane Kelly wrote in the Fall 2005 issue. And some listened. The focus of groups like Heritage Port Hope (HPH) is to conserve the substance of bygone days while promoting rehabilitation to save it from decay. As Watershed noted, HPH has also been involved as a consultant in several new developments.

The 20th century passed an attractive legacy to its successor. But the legacy comes with a price tag.

What kind of property can you pick up for $72,000 these days? Cobourg resident Felicity Sidnell Reid remembers paying just that for her small house back in 1998. Watershed reported that in 2005, the average house price in the West Northumberland area had climbed to around $175,000. Those were definitely the days – buyers are now bidding against each other to pay four times that.

In parts of Prince Edward County, house prices that peaked at around $300,000 in 2000 are now selling in the millions, according to veteran County real estate broker Shannon Warr-Hunter.

It may seem that people are flooding in, but that’s not strictly true. Since 2000, population growth has been steady, but not rapid – just over 10% in Northumberland during the Watershed years. But the demographic itself is changing. Until recently, population growth came traditionally from the over-50 crowd; today, though, people are not just coming for retirement.

Shannon Warr-Hunter has seen that shift in the age of home buyers accelerate in the past year, with more young people and first-time buyers. “The prices in the GTA make it feel impossible for some to ever think they’ll afford a place,” she says, “and Prince Edward County has a lot of draw for those folks now: great creative community, outdoor activities, beaches, fine wine and farm-to-table dining, smaller schools and a broadening coverage of highspeed internet so people can work from home.” Shannon doesn’t see this trend slowing down any time soon.

Our part of the province has long been a desirable destination for people leaving the city for a sweeter life. It seems people just plain like to come here. Life-long Port Hope resident Peter Abrams has seen a great deal of change in his seven decades, but he believes that the best parts of his hometown are the things that never change. “So many people really enjoy the environment and feel of the place. It’s a family-friendly town and has a very welcoming atmosphere that attracts people.”

We can hope that our natural environment is as lucky; there always seems a reason to keep a watchful eye, from low-level nuclear waste to someone trying to bulldoze our vital green spaces and wetlands in the interests of another industrial park or highway. As the Fall 2019 issue pointed out, our conservation authorities are currently under fire from our own provincial government. The land is ours to discover, as the licence plates say, but it is also ours to protect.

CFB TRENTON

The 21st century has thrown major changes at the Canadian Forces’ busiest airport.

The principal mandate of 8 Wing, CFB Trenton’s main tenant, is military transport. This role was unexpectedly ramped up in the early 2000s when the war front opened up in Afghanistan. An article in the Winter 2006/07 issue described the mission to move personnel and equipment to the other side of the world, little realizing it would last for seven more years. In 2007 CFB Trenton became the originating point for the Highway of Heroes, bringing fallen Canadian soldiers home from battle.

The mission is over and the troops are home, but the work continues. CFB Trenton is the largest single employer in the Quinte West area, with nearly 4,000 regular and reserve force members and an additional 500 civilian workers. Three-quarters of military families live off base – part of the larger communities of Trenton and Brighton. The social and economic impact to the community is huge.

Nowadays 8 Wing delivers supplies to the high Arctic and undertakes life-saving search and rescue and humanitarian missions. And their work during COVID has been a godsend, most recently with the air transport of much-needed ventilators to India.

ONWARD AND UPWARD

One thing that hasn’t changed in twenty years is the open, friendly lifestyle of Watershed country. This aligns perfectly with the magazine’s original mandate to uniquely connect with the richness of the community and to tell its stories.

The amount of information, history, advice and humour that’s been communicated in twenty years is overwhelming. Any milestone is significant, however, only as much as it provides a springboard to the future. Watershed pays its dues with every issue, always striving to make the next one better than the last – a tough challenge with the bar always so high. But it’s a challenge we meet with joy.

What’s ahead for the coming years? Will the magazine still be distributed primarily as a paper publication or will it spread out to other media such as podcasts? Will online forums feature discussions of articles? Will a restaurant review feature a Zoom visit complete with food delivery? One thing the pandemic has taught us is that the sky is the limit when it comes to connecting people in ways no one has thought of.

Let’s meet between these pages – virtually or literally – in another twenty years, and find out.

Story by:

Chris Cameron

Photography & Illustrations by:

A Talented Team of Artists