Luna Moth

From left: Eastern red-backed salamander; American bittern; shagbark hickory

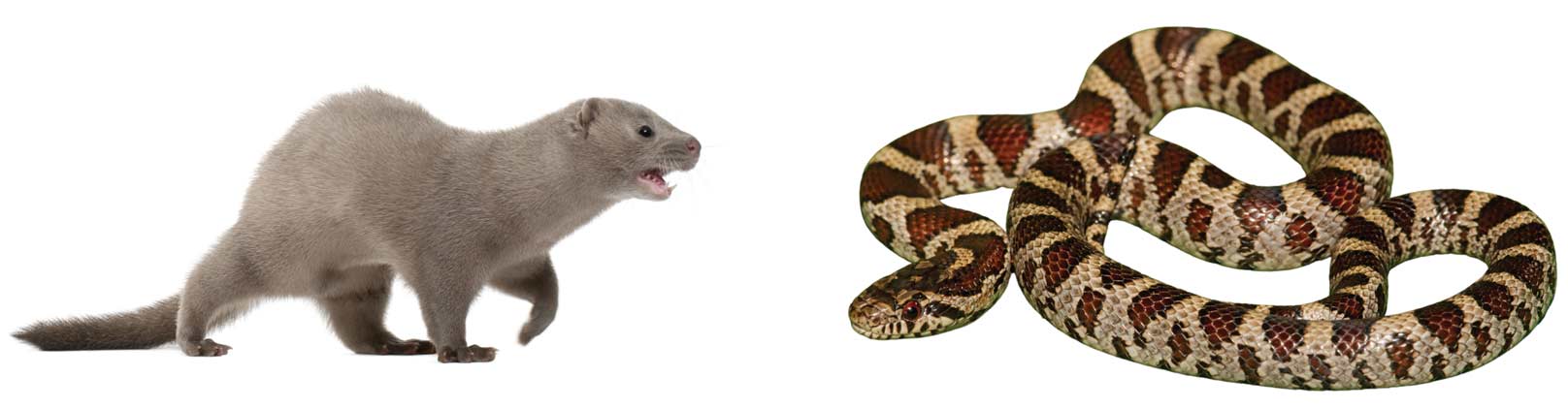

Left: American mink; right: milk snake

If you think you need to travel out of the country or out of the province to see exotic, colourful, rare and sometimes even weird plants and animals, think again.

With patience and a willingness to explore our forests, wetlands, shorelines and meadows, we can find plenty of natural treasures right on our doorstep. Let’s go on a walk together. As we set out, we’ll discover many of the region’s protected lands which, under the stewardship of conservation authorities, provincial parks, the Nature Conservancy of Canada and local land trusts, provide the all-important habitat that animals and plants depend on. Bring your binoculars, bug spray and a camera, and let’s go explore. We’ll tread carefully, keep our distance, and give these treasures the respect they deserve.

LUNA MOTH

If we head into the woods at night in June or early July, we might see a luna moth; it will be a sight we won’t soon forget. One of North America’s largest moths, measuring about the size of your open hand and lime green in colour, the luna’s list of exotic features includes spectacular black-and-yellow eye spots on its wings meant to scare away predators.

From there, things just get weirder. To start with, the luna has no mouth. For its two short weeks as a fully-developed moth, during which it finds a mate and lays eggs, the luna relies on food it gathered as a caterpillar in the hardwood forests. Lunas spend the bulk of their lifecycle, including the winter months, as pupae inside a cocoon.

Luna moths are less abundant now than in the past. They navigate by moonlight and become confused by artificial bright lights. Sadly, they are also hunted by the parasitic flies that have been introduced to control spongy moths (formerly called gypsy moths). We’ll keep our eyes open for them at dusk on the edges of hardwood woodlots and conservation forests where, if we’re lucky, we might see one silhouetted by the moonlight, looking for a mate.

As our Ganaraska and Northumberland forests mature, a combination of selective harvest practices and natural processes are encouraging increased species diversity among the red pine and other softwoods planted to stabilize soils in the mid-1900s.

AMERICAN BITTERN

Secretive and elusive. These are words you’ll often read in descriptions of the American bittern. They manage to avoid being seen despite their relatively large size – about the same as a mallard duck. But with their long necks and white, brown and black striping, they are perfectly camouflaged to blend in with their favoured habitat – marshes with tall vegetation.

Bitterns are masters at standing still and moving slowly. However, they strike with lightning speed, dining on fish, amphibians, insects and even small mammals. These days their population numbers are down, as wetlands are disappearing due to development and conversion to farmland. All the more reason to celebrate places like the H.R. Frink Conservation Area north of Belleville which has a 500-metre boardwalk that accesses a secret wetland and its inhabitants. It’s a great place to start our search for this treasure. Let’s make sure we take our binoculars and bug spray on this outing.

EASTERN RED-BACKED SALAMANDER

As forests mature, their floors amass leaf litter and rotting logs, and they develop distinctive “mound and pit” terrain from trees uprooted by storms. This is the perfect, and in fact only, habitat where we’ll see the eastern red-backed salamander, a small amphibian about the length of your finger whose distinguishing features include a red dorsal stripe.

Like many other members of the salamander family, the eastern red-backed has no lungs. Instead, it breathes through its skin, making it especially sensitive to moisture and temperature. When the weather is hot and dry, the salamanders retreat under logs and rocks or into the moist soil of the forest floor.

Red-backed salamanders eat mostly insects, along with small invertebrates such as millipedes and spiders. This time of year they’re busy mating, producing eggs that will hatch in a couple of months. Peter’s Woods Provincial Nature Reserve, north of Centreton, provides the ideal habitat for the eastern red-backed salamander, where it thrives in the moist, woody debris and leaf litter found in the mature, mixed forest. However, over time, both the Ganaraska and Northumberland forests will develop more old-growth characteristics, which is good news for salamanders.

SHAGBARK HICKORY

The shagbark hickory is generally considered a Carolinian tree, but as with so many things in the natural world, boundaries are not absolute; our region fits neatly within its range. It is distinguished, when mature, by its shaggy bark which gives the tree its name. Younger specimens are smooth-barked.

A full-grown shagbark is an impressive sight, standing over 100 feet and capable of living up to 350 years. They’re an important wildlife tree, growing nuts that feed species including red squirrels, raccoons, bears, foxes, wood ducks and wild turkeys. Humans also enjoy the nuts, which are delicious and can be substituted for pecans. Unfortunately, crops are unpredictable, so the shagbark nut is not a candidate for agricultural production.

As our Ganaraska and Northumberland forests mature, a combination of selective harvest practices and natural processes are encouraging increased species diversity among the red pine and other softwoods planted to stabilize soils in the mid-1900s. This means hardwoods such as the shagbark hickory will increasingly join the mix of trees. Along with their distinctive bark, we look for the five-bladed hickory leaves, and in a good year, clusters of nuts.

MILK SNAKES

Pity the poor eastern milk snake. Too often humans will stumble across one and decide they must kill it on sight, confusing its red and brown markings and tail-rattling behaviour with that of the venomous Massasauga rattlesnake, which in Ontario is found mainly around Georgian Bay and certainly not around here.

The milk snake gained its name from the mistaken belief that it takes milk from cows in barns, where they can often be found. But instead of being threatened or repulsed by milk snakes, we should appreciate that they help control pests by feeding on mice and other rodents.

The milk snake hibernates underground in rotting logs or in the foundations of barns or old buildings. Come spring, the females lay eight to sixteen elliptical eggs in decaying logs, stumps and small animal burrows. These eggs will hatch in August or September. The snakes mature in three or four years, growing up to a metre in length, and can survive seven to ten years in the wild. Human threats, besides cases of mistaken identity, include habitat loss and death by car tire.

AMERICAN MINK

We shouldn’t miss out on a walk along a rocky shoreline on Lake Ontario at, say, the Point Petre Conservation Area in Prince Edward County. If we look carefully among the rocks, we might see a glossy brown creature streaking along, a rolling sine wave. It’s not an otter – too small for that – or a weasel. We’re seeing an American mink, which not only runs impressively well, but also climbs trees and is semi-aquatic, able to swim three hours in warm water. Over time, the mink has adapted to aquatic life, acquiring a lowered heart rate, which helps it dive for food.

Not surprisingly, the mink dines primarily on fish, crustaceans and amphibians, although it will also feed on mice and even large birds such as seagulls and cormorants, which the mink will drown despite its apparent size disadvantage. Minks breed in late February, and at this time of year they are raising their just-born young, which will stay close to mom until fall and reach maturity next spring.

As we walk along the shoreline, we may catch a glimpse of a mink and her babies darting for cover between the rock crevices and the bushes.

Story by:

Norm Wagenaar