If the walls of the Waddell Hotel in downtown Port Hope could talk they’d surely tell the story of J. A. L. Waddell – an engineer who set the standards for bridge design that are still consulted today. It’s a local-boy-makes-good story that just might surprise you.

When it was new in 1845, the Waddell building was the most fashionable commercial address in town. It was a multi-purpose edifice that housed a bank and shops on the main floor and a hotel on the second and third. The building was the brainchild of Robert Waddell – sheriff, bank agent, miller, developer and hardware merchant. He enlisted the best architect he could find, namely Toronto-based William Thomas, who would later go on to such architectural triumphs as the St. Lawrence Hall and the Don Jail in that city.

Ireland-born Robert and his New York-born wife, Angeline started out in a Georgian townhouse that still stands just above the railway tracks on King Street. Robert’s duties as sheriff soon took the family to Cobourg, where all three of his sons studied engineering. The eldest, John Alexander Low Waddell, went on to higher education, in fact, much higher education. In an era when few went to high school, John graduated from Trinity College School in Port Hope, travelled extensively as a teen through the Far East and ultimately earned two civil engineering degrees: a bachelor’s from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute near Albany, New York, followed by a master’s from McGill.

John began his career humbly enough, working as a draftsman for the federal government in Ottawa, before he returned to the U.S. in the early 1880s as an agent for a consulting firm where he worked as an engineer in the design and construction of several bridges.

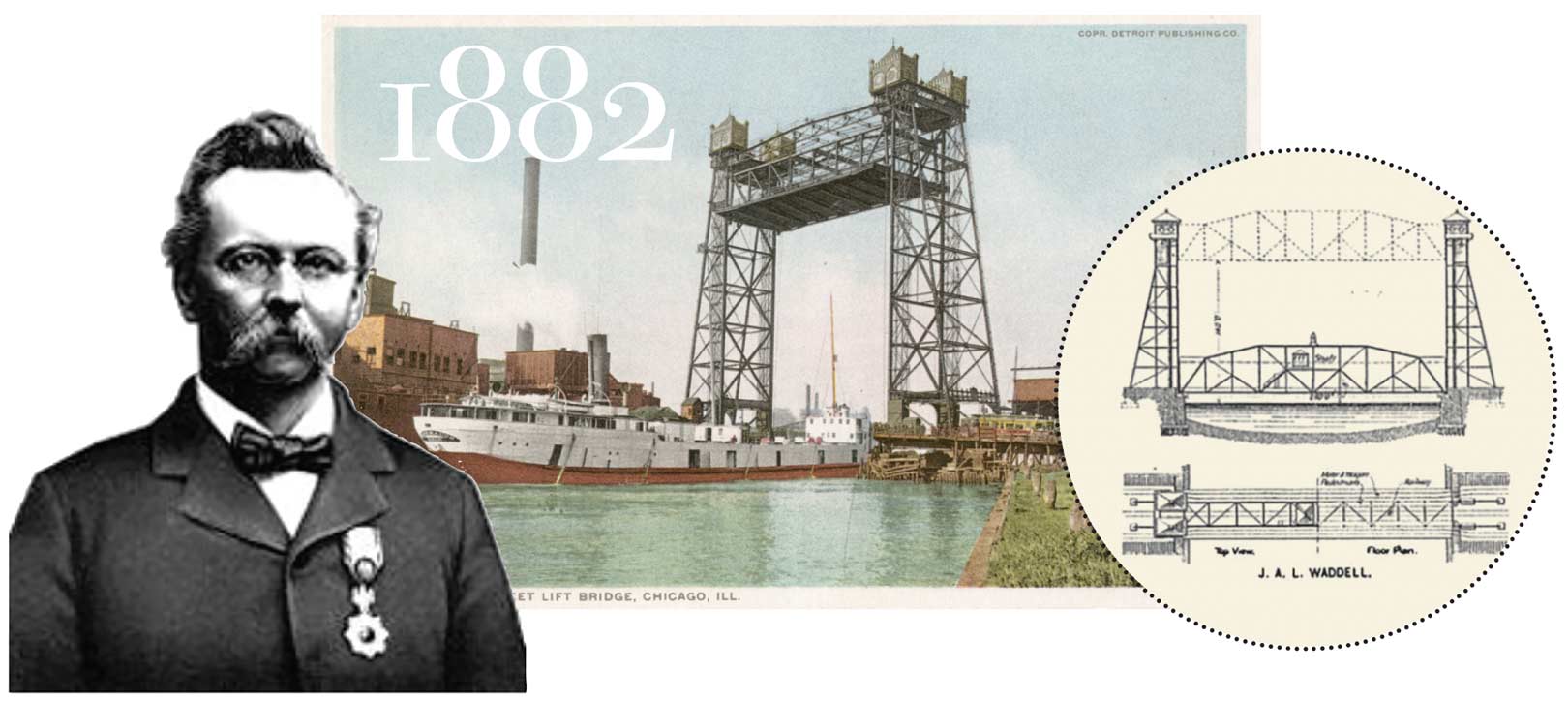

In 1882, John Waddell’s star rose like a rocket. He was recruited to teach engineering theory at the Imperial University of Tokyo and was one of the essential “foreign employees” hired by the emperor’s government to modernize Japanese infrastructure. It was in Japan that he wrote the first of several books, The Designing of Ordinary Iron Highway Bridges, which still serves as a primer for bridge-building. Ultimately, his greatest expertise was the design of “movable” railway bridges, heavy iron and steel structures that could be swung or lifted to allow passage for boat traffic below. Among Waddell’s first commissions upon his return to America was a swing bridge over the Missouri River at East Omaha, Nebraska, which at the time was the longest bridge of its type in the world. In 1894, he built the world’s first major vertical lift bridge over the narrow channel of the Chicago River. It wasn’t merely his design; it was his invention, a type he patented.

Waddell settled in the fast-growing city of Kansas City, Missouri, where he hung out his shingle as a private consultant. Through various partnerships, his firm evolved and expanded, eventually opening new headquarters in 1920 in Manhattan, where under the current name Hardesty & Hanover, it functions to this day, still building lift bridges. Waddell died in New York in 1938, at age 84, still active in his field. In his lifetime, he was instrumental in the design and construction of up to 1,000 bridges. Some were – and still are – major engineering marvels.

Waddell’s clients included a few Canadian railway companies, but there is scant record of his work for them. He was certainly never active back home in Port Hope, although there’s something poetic that not one, but two railway viaducts – engineering feats in their day – cross the Ganaraska Valley mere steps from the King Street house in which Waddell grew up.

The family hung onto the old hotel property at Mill and Walton until Robert’s death in 1889. In the years afterward, the building fell into obscurity until it was gloriously restored in the 1990s. Even so, the Waddell story isn’t well known, even among history buffs. Who’d have thought a local boy from Port Hope would go so far?

Story by:

Tom Cruickshank