Last month, as my kids gathered at the dinner table using FaceTime to celebrate my youngest daughter’s 24th birthday, I heard them all agree there was no point trying to buy a house because the planet is going to shake off the human race like a bad cold over the next 40 years. They are unanimous in their view that our species is doomed. This quiet acceptance of the end times coming from my own brood gave me a bit of a start. But then my wife observed that I have not had to sit through as many classes on disappearing species as they have. They have been fed such a steady diet of melting ice caps, vanishing forests, rising carbon levels and general climate gloom that you really can’t blame them for taking the dark view.

As a young man, I recall being quite anxious about the collapse of humankind. I grew up with the atom bomb, acid rain and stagflation. My parents were also gloomy people but they probably did more to earn the right to be glum, having lived through the Great Depression and a world war. My mother’s father was the gloomiest of the lot. He graduated from Harvard medical school the year of the Spanish Flu epidemic in 1919 and then ruined every dinner party for the next 50 years with his lectures on the great pandemic to come.

Quite a few people in my school year went to extraordinary lengths to prepare for society’s collapse. One of them stockpiled copper pennies in pails in his parents’ basement in the 1970s, believing that copper would eventually be worth as much as gold. He collected nearly half a ton of pennies and watched copper rise from 50 cents a pound to a dollar. Then it went back down to 62 cents, barely budging from that over the next 30 years. His wife finally made him get the penny pails out of the garage and sell them all to a scrap dealer about an hour before the price began a steady climb to four dollars, where it sits today. In the meantime, we passed through several panics but no collapse.

Humans have always been tempted to think their own generation has plumbed a new depth in human experience. Perhaps the prize for bleak thinking should be handed to the Europeans of the 1300s when the continent moved into the Little Ice Age. The famine of 1315 – 1322 killed millions and the survivors were convinced the world must be coming to an end. Doomsday images appeared on the walls of every church in the land. Then the Black Death struck. People were so ground down physically and mentally at that point they barely had the energy to fight back against a plague. By 1360, Europe had lost a third of its population.

But the world did not end. Astonishingly, agricultural output recovered completely within a decade and Europe began an economic rocket ride that, in spite of several notable interruptions, continues to this day.

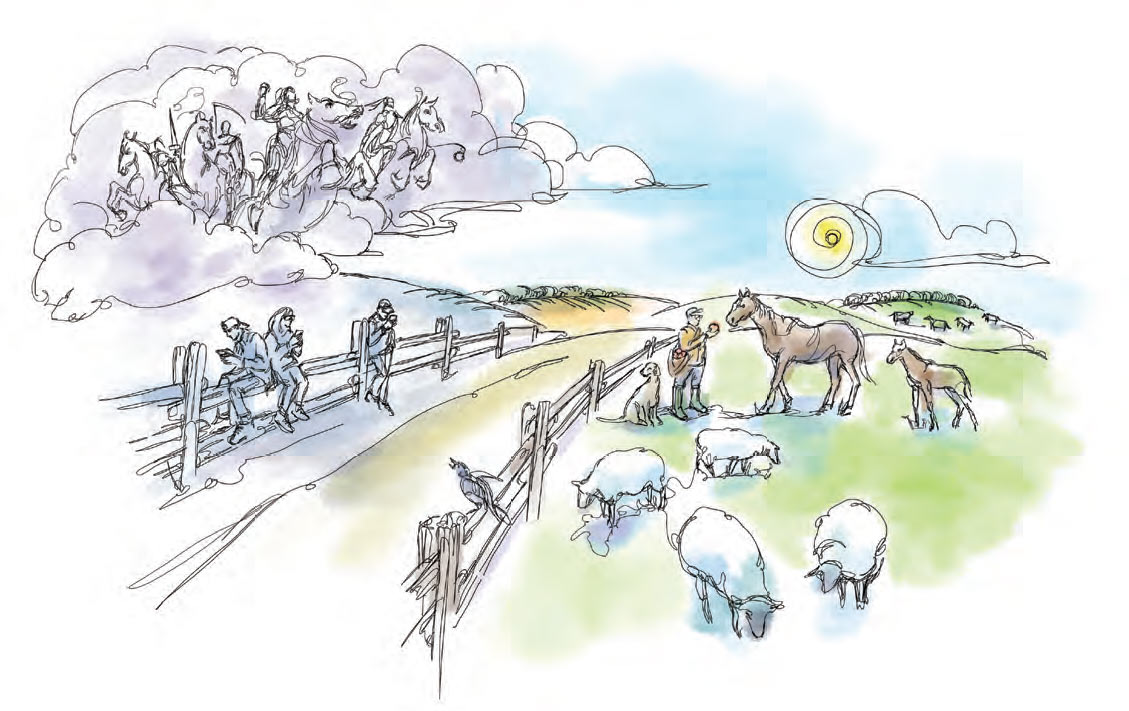

As a scribbler I have always walked down the sunny side of the concession roads. I found it was the side less travelled for my generation, so I had a lot less competition. Everybody else was writing dark stuff. I have always tried to help people feel a little better about the world by reminding them of the vigour and humour of my neighbours. I learned to be entertained by the voices of those who have struggled through hard times and learned to watch for breaks in the clouds. There is an old saying among sailors that the weather is a great bluffer, and human society is a lot like that. The world has always seemed about to be engulfed by the storm … until suddenly it isn’t.

At the online birthday party, I reminded my children it is never a good idea to put all your money on one square of the roulette wheel. There can only be one apocalypse, by definition, and our record of predicting that event has been very poor. Prediction is not the strong suit of our species. We just end up with pails of pennies in the basement. Our real skill is coping with setbacks when they occur, which is why there are now nearly eight billion of us on the planet.

So I encouraged the children to take the long view, which may not offer the thrill of apocalyptic thinking, but may in the end be more useful. Times are indeed tough … but will you be ready when they get better?

Story by:

Dan Needles

Illustration by:

Shelagh Armstrong