To make jam is to put the County summer sunlight in a jar, preserving it forever – or at least, as long as our stores last.

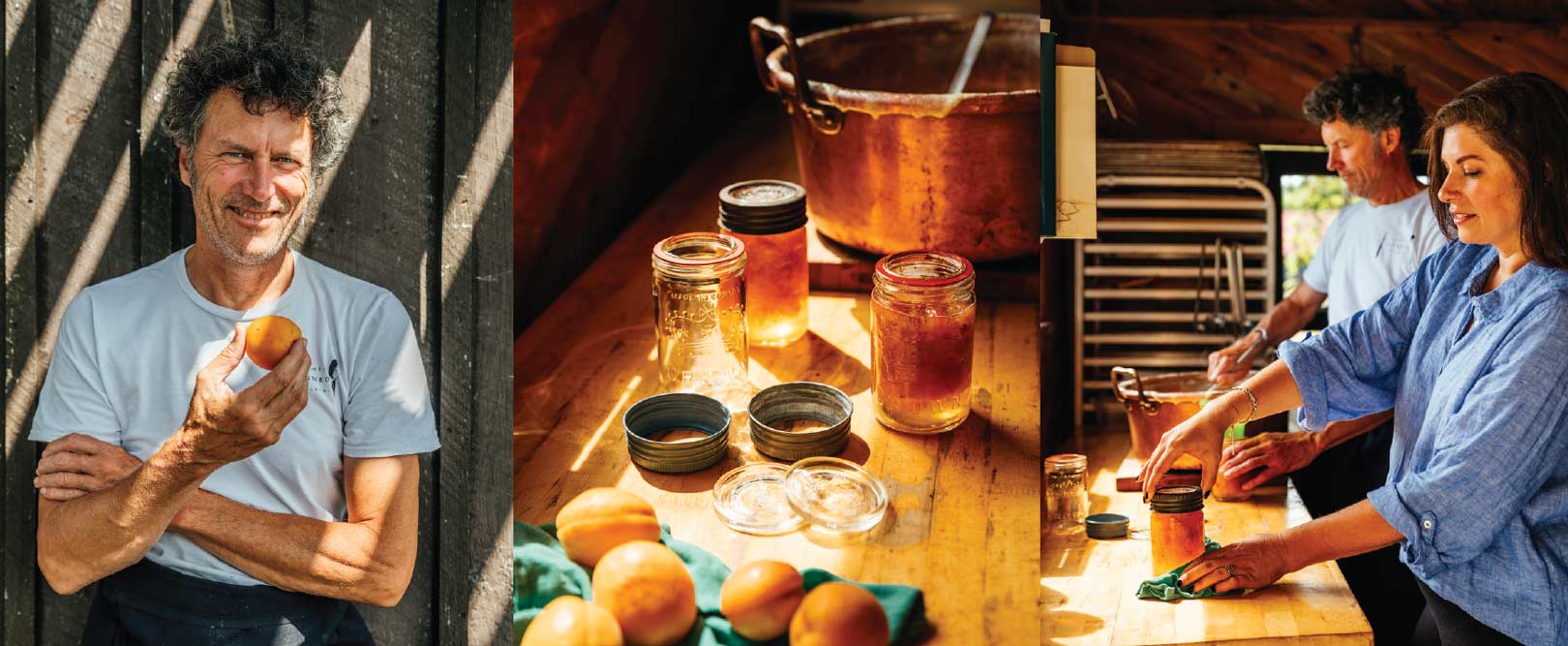

The sweet, tropical scent of simmering apricots and melting sugar wafts warmly through Jamie Kennedy’s century-old barn kitchen in Hillier. On the stove, a thick, frothy brew is bubbling away in an enormous copper pot. Jamie has stepped out for a minute and he’s left me in charge of watching the golden mixture, making sure it doesn’t boil over. Everyone knows I’m a total amateur in the kitchen, but I can handle this much. The concoction reaches upwards again, pushing towards the brim, but Jamie has shown me how to carefully skim the film that forms around the edges and when I do, the mixture, relieved of some pressure, settles back into its lively, level rollick.

There are few food fans out there who don’t know the name Jamie Kennedy – Toronto’s influential chef, restaurateur and author, whose legendary commitment to environmental issues and support for organic agriculture, local producers and traditional culinary methods led the Canadian revival of the original food scene – the shortest route from the farm to the table. In 2010 Jamie received the Order of Canada for championing Canadian cuisine and organic, sustainable, close-sourced food, and six years later he moved, full-time, to the 115-acre farm he’d bought in Prince Edward County in 2001.

Jamie was laying a table with a new view, embedding the experience of food into the land that mothered it. It was a move not unlike the one his Scaramouche kitchen-mate Michael Stadtländer made in ’93. Chef Stadtländer’s Eigensinn Farm in Singhampton felt like part elite epicurean experience and part social experiment, but this “ground zero dining” was a serious thing, receiving endless praise from those who made it to the table. Jamie’s dinner series were that same kind of magic, blessing us with culinary experiences that exhibited the best of local farming – from hot-smoked whitefish to our Burgundy-esque wines. There was also the launch of JK Fries, the soon-to-be-famous food stand at the Wellington Market, every Saturday from May through the end of October. Jamie’s incredible talent quickly made fry-fans out of the locals and called to the hordes of city folks who craved their fix of his famous fare.

We’re outside the barn now, relaxing under an enormous old maple, with its branches stretched across the little beer garden as Jamie explains his approach to making jam. He takes one of the pastel spheres out of the bowl and hands it to me to study, while expertly slicing its brothers into relatively perfect segments. “So, I look for apricots that have really firm flesh like this one,” he says, and I rotate the fruit in my fingers, holding it above my head so the mostly opaque object shades my eyes from the sun. “The smaller ones that are more yellow, more deeply coloured like these are the best – and they look great in the jam.” Jamie sourced this fruit from a farm in Niagara, and even then he had to push his suppliers to look hard for it. In a 2010 interview together, we’d discussed the trend of seeking out food that came from farmers whose names you knew, and Jamie pointed out that with all artisanal and local produce, the market’s support is crucial for their survival and that “purchasing ingredients is an exercise in supporting a local grower in a sustainable and qualitative way.” It was a lesson that stuck with a lot of us.

“Do you need me to peel something?” I offer and Jamie shakes his head. “You leave the skin on and it just disappears.” He looks up from the fruit and his eyes glint as they catch mine, the corners of his lips turn up. “And then I’ll show you why I’m keeping the pits, because inside there’s something that’s like a bitter almond, and if you add some of those in and cook them down, it will give the jam another profile.” I love this and also that the relatively straightforward act of making jam can be complicated – depending on who’s behind the jar.

We’re inside now and beams of sunlight are shining through the old barn windows and onto the raw wooden floor. I can’t stop thinking about how what we’re doing is the beautiful culmination of a 48-year career in food. “I worked in a kitchen full time from when I was seventeen,” Jamie says, marking the origins of his journey. “In my report card, my teacher described me as a ‘sprightly, fun kind of guy.’” Now in his early 60s, Jamie is all untamed hair, angular limbs and gentleness. He speaks softly through a consistently genuine smile, his sincerity shining through every careful word. He’s still fun, smart and undeniably versatile – anyone who’s seen his knock- ’em-dead rendition of Talking Heads’ “Life During Wartime” on stage at our friends’ annual barn burner can attest to that. Is it an extraordinary sense of discipline or some other element of character that makes the greats great, I wonder, or are some people just … great?

“From the beginning, it was more than a job.” He pauses and I nod, trying to imagine a young Jamie Kennedy, hungry for a culinary education. “But saying that it was a calling is a bit heavy handed. It was more that I understood the scope of what it took to be a cook. I understood all the realities, and I still loved it. I had a passion for cooking, and with cooking, it’s a thing that’s renewed daily: you work all day in a restaurant, you go into service, and then you do it all again the next day. That short-term gratification was important for my personality.”

Now Jamie is masterfully cracking the apricot pits, tossing the innards into the pot. “It was a clear choice then,” he says, reflecting back. “I got a job at a hotel and started a formal apprenticeship. There was funding from the Ontario government at that time to support it, and I went for it. The apprenticeship took three years and after that, I did what I originally intended and went to Europe – two years working in Switzerland, honing my skills. It was a wonderful, wonderful time of my life. I would do it again in a heartbeat.”

It wasn’t that long ago that Jamie was hanging out with a bunch of us on one of the County’s secret beaches. Despite the raw scene, he was carefully crafting something delicious: sardines on thinly-sliced bread with homegrown tomatoes, cucumbers and pink radish-pickled onion. The sun shone hard and we sat scattered on woven blankets, munching happily under trees that leaned over the sun-dappled sand. We gazed out at the little waves that lapped over smooth water stones.

“From the beginning it was more than a job. I understood the scope of what it took to be a cook. I understood all the realities, and I still loved it.” JAMIE KENNEDY

The sunny seasons in our little slice of Ontario are always too brief, but while we milk every drop out of them, pretty blossoms transform themselves into sweet fruit. We had quickly learned the ritual of the harvest: gather everything that matures in the time we have and consume all we can before leaning into the ancient practice of preserving the excess to buffer the fallen blanket of gold and orange leaves that soon subsides to snow. To make jam is to put the County summer in a jar, preserving it forever – or at least, as long as your stores last.

Now we’re back inside and I’m leaning forward to see the contents better while Jamie squints at the screen of the temp gun he’s aiming at the gurgling mixture. It’s just syrup right now. After mixing roughly equal parts of sugar and fruit, Jamie left the apricot pieces in for just long enough to release most of their water, then strained and put them to the side so the fruit would retain some freshness when it was introduced back into the mix after the syrup reached the right consistency. “We need it to hit 220° to get to the gelling point,” he says, grinning as I blink, clueless. “That’s when it’s like a nice spreading consistency rather than just components, so it just sort of sits up on the toast a little bit.” This makes sense.

Actually, apricot jam isn’t just a breakfast food and it’s more culinarily versatile than most people think – from savoury to sweet executions, but Jamie is a purist, shaking his head when I ask about other cool ways to incorporate it. “I don’t know, Lonelle,” he deadpans, “just the flavour of it – it’s unique, like blackcurrant.” I’m learning a lot of new things about Jamie today. Before coming, I’d imagined that making real farm-to-jar jam with the “King of the Kitchen” would be immersive and messy. I’d have fruit pulp all over my hands and juice dripping off my elbows; but instead, Jamie has everything washed and prepared, his kitchen is controlled and strategic. For Jamie, food is serious business and those pretty apricots have a clear and beautiful destiny.

“How many jars will this make?” I ask, guessing how far the contents will stretch as he ladles the molten gold from the pot into small glass jars awaiting their pretty lids. “About twelve,” Jamie answers, eyes on the process. “Oh, so you’ll use the jam in something else then – not sell them by the jar,” I speculate aloud, trying to understand how such a large amount of care and energy could pay off in this economy. “No,” he smiles up at me, and it’s suddenly clear that the ritual is its purpose. “This is just for my toast.”

Before moving to Prince Edward County, Lonelle Selbo worked in Toronto as the editor-in-chief of YYZ LIVING, LUSH, MüDD and other beautiful fashion and lifestyle publications – but always maintained a relationship with her first love, writing. She spends her time being everywhere there is to be, inhaling the County’s infinite green-blue and pale-gold vistas, soft white sands and magical limestone soils – wild inspiration and precious history filling the cracks in-between. Her County publication LIFE AU LAIT, lifeaulait.com is dedicated to capturing the heartbeat of the County from the inside.

Story by:

Lonelle Selbo

Photography by:

Johnny C.Y. Lam