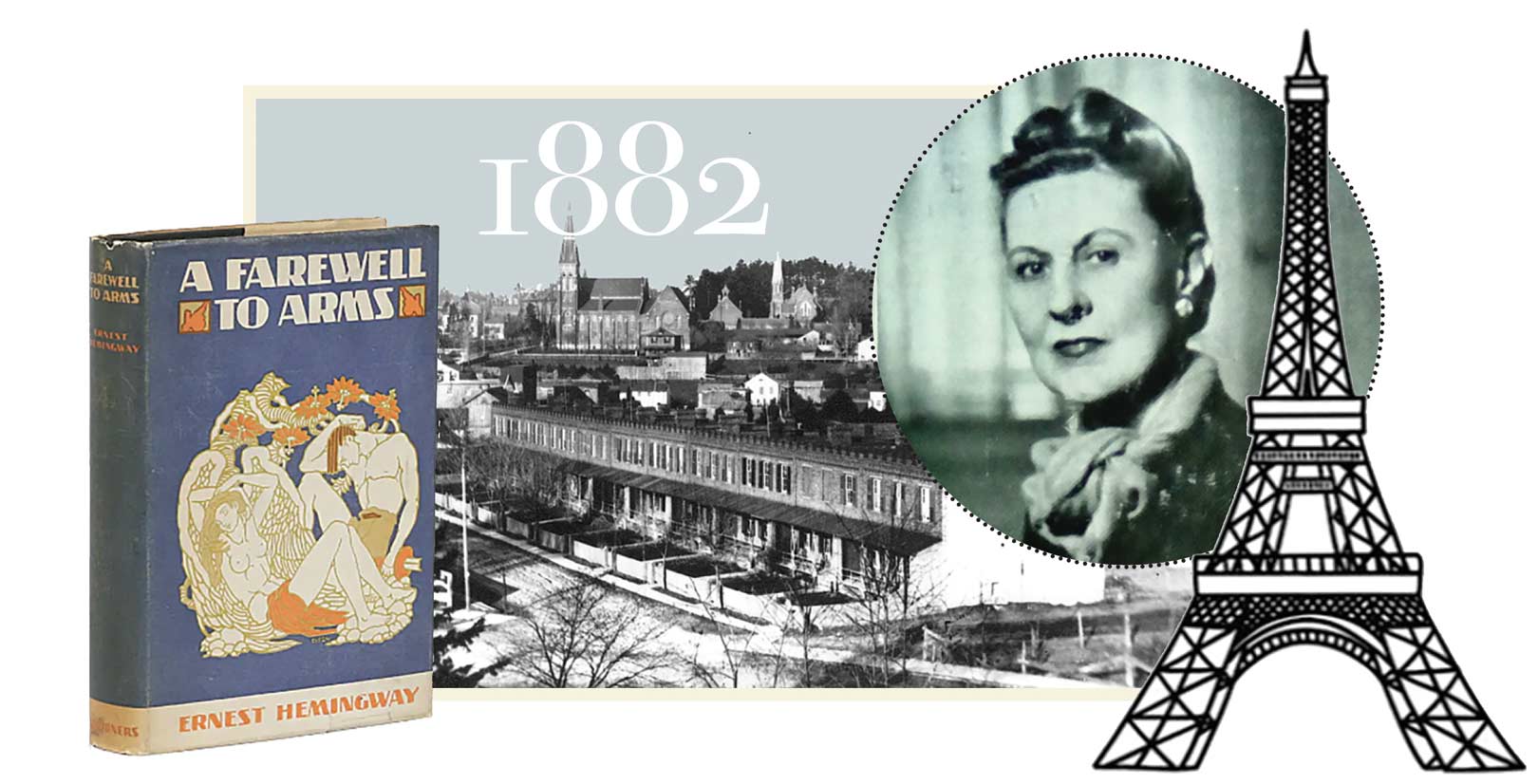

She lived an exotic life, especially for someone born in the Victorian era. Married, divorced, married again and childless, Kathleen “Kitty” Cannell (née Eaton) moved around artistic circles in free-spirited Paris between the two world wars. She indulged numerous lovers, but more importantly, she was an independent thinker who had a career that spanned decades, first as a dancer and later as a fashion writer. At a time when respectable women rarely left the home, hers was a lifestyle that could make great fodder for a novelist; in fact, a famous writer likely used her as a model for characters in not one, but two of his novels. That author was Ernest Hemingway.

Born in upstate New York in 1891, Kathleen was a toddler when her mother fled her tumultuous marriage to a notorious playboy. With her three little children in tow, Kathleen’s mom found refuge at her family home in Picton, where they lived in splendid luxury in one of the most lavish mansions in town. Surrounded by an ornately balustraded fence, Maplehurst stood beside the Methodist church, in full view of the local townsfolk, and left no doubt about the wealth and status of Kathleen’s grandfather, Charles Stewart Wilson, a man still remembered in the history of Prince Edward County.

A rags-to-riches lumberman and private banker, Wilson had a profound influence – not necessarily a good one – on his granddaughter. Kathleen later described him as “so determined not to be a snob that it made him the biggest snob ever. That his snobbery was in reverse made it none the less flagrant. He never got over the fear that Pictonians might accuse the barefoot boy of putting on airs.”

Grandfather Wilson ruled the house with an iron fist and made his presence known even after his death. In his will, he instructed his executors to disinherit Kathleen’s mother should she ever reconcile with her gold-digging ex-husband. And while he left sizable annuities to his grandchildren, including Kathleen, he made sure that “the complete story of their father’s conduct be told … as he or she is paid each sum of money coming to him or her under this, my will.”

It must have been a relief when Kathleen’s mother pulled up stakes once again, this time moving her children to Port Hope. There, they rented a townhouse in a 12-unit row called Barrett’s Terrace, which is today a much-admired heritage landmark on the edge of downtown. Kathleen remembered it fondly: “[We children] explored the roofs with a view to aerial games… Although flat, the roofs had possibilities, for you could run from one end of the terrace to the other, vaulting over the low brick barriers that separated the 12 housetops.”

However, as she grew into her teens, Kathleen found the same provincialism in Port Hope that she had seen in her grandfather in Picton. She was critical of the elitism that seemed out of place in such a small town, adding that “‘big-feeling’ – feeling oneself better than others” – was universally condemned by polite society but in fact was “definitely the attitude of the town’s aristocracy.” Kathleen despised such double standards and vowed to escape. She soon left for Branksome Hall, a private school for girls in Toronto, and never looked back.

Kathleen headed for Paris around 1910, where she studied music and dance at the Sorbonne and became immersed in the expat arts community. The decade of the 1920s in France was coined les années folles – the crazy years – to describe the social, artistic, and cultural collaborations of the period. The City of Light became a cultural magnet for artists from around the world – where the likes of Ezra Pound, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Pablo Picasso took up residence.

Kathleen was friendly with leading Imagist poet William Carlos Williams. She obviously made an impression; he described her as: “Kitty Cannell in her squirrel coat and yellow skull cap, which made the French – man and woman – turn in the street and stare, seeing a woman, approaching six feet, so accoutered.”

Another poet among Kathleen’s Paris peers was Skipwith Cannell, to whom she was married briefly. She was also romantically linked to Harold Loeb, scion of the wealthy Guggenheim family and founder of the avant-garde Broom magazine. Eventually, she married again, this time to Roger Vitrac, a poet-turned-playwright who was a leader in the surrealist movement.

All are familiar names to students of 1920s arts and literature, but none is as familiar as Hemingway, who travelled with Kathleen’s crowd while posted in Paris as foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star. By one account, neither was particularly fond of the other, but still, you have to wonder if conversation ever turned to their mutual connection to culturally staid, prohibitionist Ontario.

It was during this time that Hemingway drafted The Sun Also Rises, his first novel, and many have wondered if one of its characters – Frances Clyne – was based on Kathleen. She probably didn’t take it as a compliment – Frances was a manipulative social climber, possessive and jealous – in fact Kathleen denied it. Nor would she have been flattered to know, upon reading A Farewell to Arms (1929), that a judgmental, unhappy character named Helen Ferguson was also modelled after her.

Kathleen’s reflections on her early life come to us in her memoir, a 1945 romp titled Jam Yesterday, which she wrote while living in Paris, about as far from small-town Ontario as you could get. There she sat, waiting out the Nazi occupation of Paris during World War II, her career as a fashion writer and dance critic stalled for the duration. Up until that time, she had been freelancing for The New Yorker and The New York Times, among other publications.

Before the war was over, Kitty Cannell got passage back to America, where she continued her career as a journalist. She died in 1974 at the age of 82. From Picton to Port Hope to Paris, Kitty Cannell had not only been taught the reality of rural life in Ontario, but she had tripped the light fantastic with legendary literary figures and frequented the salons of socialites around the world.

Story by:

Tom Cruickshank