Out here on the ninth concession, burglars are at work every week among the “view” properties along the top of the hill to the west. Break-ins and car thefts are so common that police no longer visit the scene anymore. They just take the details by phone and tell you to call your insurance company.

A friend in the insurance business tells me that cash, jewellery and electronics are the first choice of home burglars. He assures me, given the choice between a Rolex watch and a 1948 Champion root pulper that weighs 500 pounds and needs sharpening, the burglar is more likely to take the watch. Certain vehicle models are regular targets, but a farm truck with cow cartoons painted on the racks has never made the top 10 list. Since the pandemic began we hear reports of livestock rustling in the county, but again, professional rustlers are looking for something in its prime, not a donkey who is old enough to vote.

I have been burgled twice now. The first break-in occurred in 1978, when I was a weekender restoring the old frame house on this farm. Maybe break-in is the wrong word. At the time I owned just one power tool, an anemic Black & Decker circular saw that whined if it was asked to cut anything thicker than plywood. I drove off one Sunday night leaving the saw on the veranda and someone swiped it. I never got a chance to thank that burglar properly. I went straight out and bought a decent saw the next week, and it still runs to this day.

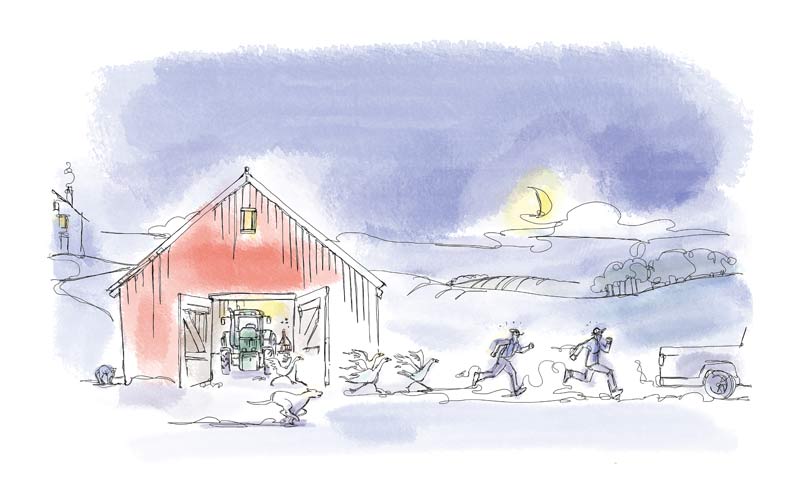

The second burglary happened many years later when my wife and I had moved here full-time and stocked the farm with livestock. Late one night I heard a truck backing out of the lane over by the barn and I dashed out with a flashlight to investigate. The truck roared off, leaving the barn doors wide open and the lights on, the dogs barking and the guinea hens shrieking. I looked around and couldn’t immediately see what they had stolen. But that’s always the way. The next morning I took a more careful inventory and realized the thieves had taken nothing. Not a thing. I should have been relieved, but I found the experience deeply upsetting. I felt violated. People I didn’t even know had dismissed all my treasures as worthless.

They have never come back. My insurance friend dropped by to comfort me and he noted that the keys were always in my truck and my tractors didn’t even need a key to start.

“What is the matter with you people?” he shouted, speaking generally to the large number of rural customers he serves who are oblivious to the simple security measures city people take for granted. I pointed out that someone could make off with the tractor in theory, but they would have to know that you must squirt ether into the carburetor before it will start. The ether can is on the bench in the middle barn where the gander sleeps, and the gander bites everyone but me. (He’d probably even bite me in the dark.) And then you would have to disconnect the manure spreader, because even I would concede it has no retail value whatsoever. There’s usually a nest of yellow jackets hanging off the tongue of the spreader – again, not the sort of thing you want to bump into in the night. So if you are thinking of taking my tractor, you might be safer just to give me a buzz first, the way the neighbours do.

In the middle of the religious wars in 16th-century France, the philosopher Michel de Montaigne decided to take early retirement from government service, leave Paris and move back to the country to write. His friends were horrified. Private armies roamed the land, looting and plundering as they went, and here was this lunatic thinking he could survive in an unfortified house. Montaigne assured them the secret was to live in a way that made it clear you had nothing worth plundering. He lived unmolested on his family estate for the next 20 years.

I have lived by Montaigne’s dictum successfully for 25 years now. Burglars are by nature averse to heavy lifting and any sort of risk. Between the age and the weight of my possessions and the bad temper of my poultry, they have decided to give the place a pass.

Story by:

Dan Needles

Illustration by:

Shelagh Armstrong