There are few Canadians whose hearts were not touched in some way by Gordon Lightfoot’s music. For nearly 60 years he wrote and sang the stories of our country and its people.

Gale-force west winds swept down Gerrard Street in downtown Toronto, swirling columns of papers and plastic up Jarvis and scattering them around Allan Gardens. It was November 10, 1975 and I was struggling against the wind, on my way to an afternoon journalism class at Ryerson. As a farm boy raised in the wilderness and now two months into the biggest adventure of my life, I couldn’t have felt more displaced if I had fallen off the back of a turnip truck headed for the Ontario Food Terminal. The ferocity of the wind that day was historic: later in the evening, the same powerful storm would sink the Edmund Fitzgerald on Lake Superior, a tragedy immortalized in the ballad by Gordon Lightfoot.

Gordon Lightfoot made a huge impression on my life in my first year away from home, when I was living in a tiny Cabbagetown apartment, a rifle shot away from Massey Hall. Before I came to Toronto I knew very little of him, other than that he’d performed in 1968 at my high school in Cobourg. Many of my first-year classmates talked about him and had seen him perform; they often caught his annual appearances at Massey Hall every March. I began chumming with a classmate and learned he was an avid Lightfoot fan. Like me, my friend was messing around on a six-string a fair bit and could play most of Lightfoot’s songs. I began listening, and soon after, a part of Gordon Lightfoot crept into my soul.

As a young writer learning my own brand of self expression, Lightfoot’s lyrics painted pictures and evoked images and emotions – enhanced by his perfect musical arrangements. Living on my own and experiencing a world as foreign as another planet, I took solace in the fact that I could relate many of his songs to the very circumstances I was facing. I was on a tight budget with every nickel spent coming out of my own pocket but it didn’t stop me from finding a record player in a Church Street pawn shop and heading over to Yonge Street to pick up the Gord’s Gold album at Sam the Record Man. Soon I had memorized every single song and marvelled at the ease with which the words flowed into the music. To this day those same songs bring comfort and pleasure any time a case of the blues happens along.

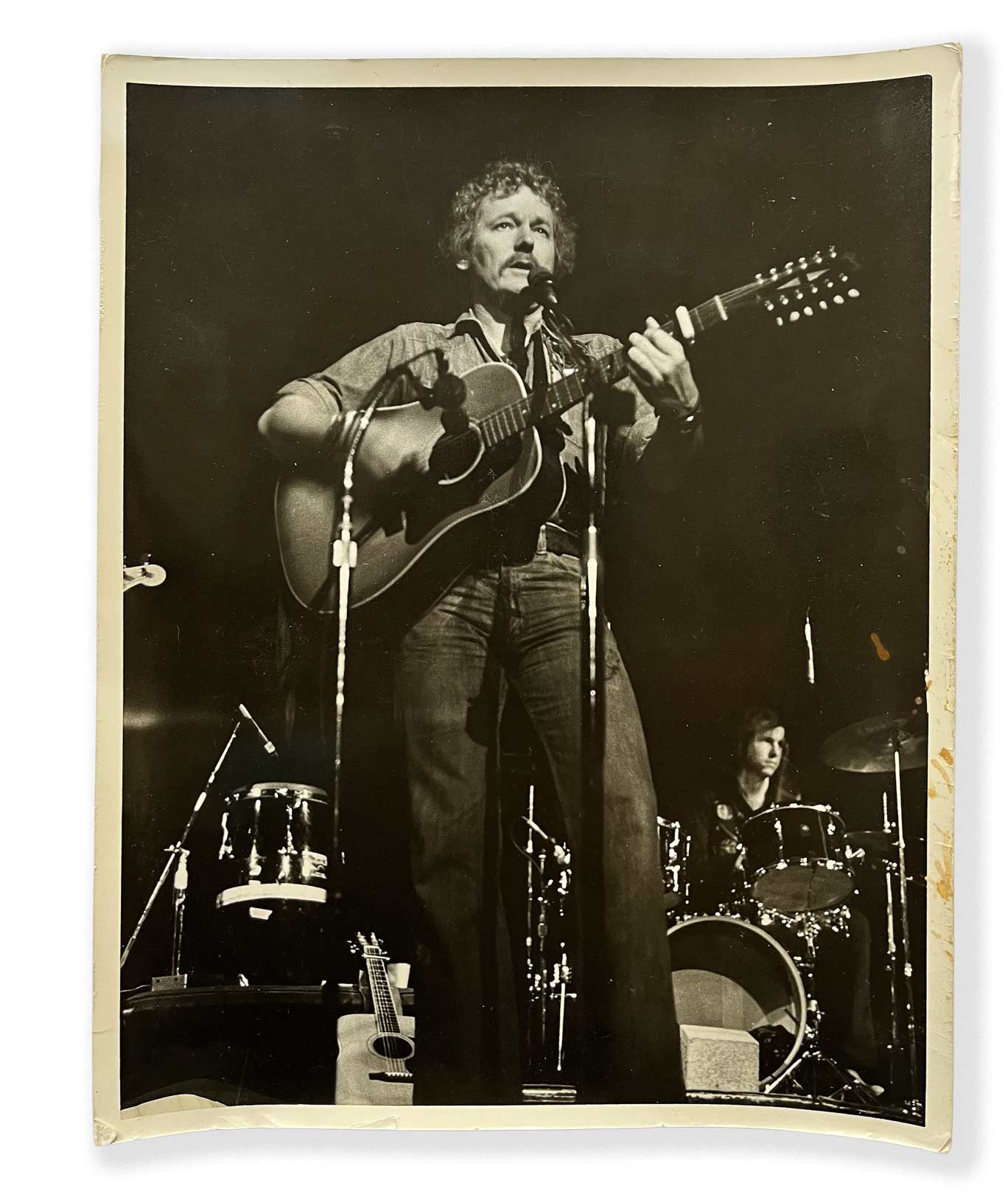

Opportunity knocked when I learned The Ryersonian (the student newspaper I occasionally worked for) was doing a feature on Lightfoot at Massey Hall. A friend who knew an usher there made arrangements for me to attend and photograph Lightfoot and possibly meet him backstage later. During Lightfoot’s second set, I got the nod from the usher and made my way to the front of the stage. My Nikon light meter indicated the exposure at F2, 1/30 of a second. Hand-held photos at a slow speed like a thirtieth of a second are iffy at best, and no flashes were allowed during performances. Four quick shots and I was back in my seat. I began trembling, praying that at least one of the photos would be satisfactory. Later, backstage for a few brief moments, I found Lightfoot casual and relaxed and he wished me well with my studies. Too overwhelmed and nervous to say anything sensible, I thanked him and stumbled out.

Some describe Lightfoot as a great storyteller, but he was much more than that to me and my contemporaries. His artistry and careful devotion to detail captured the underpinnings and stories of Canadian life. His verses are timeless rhyming poems, set flawlessly to music that creates a vivid tapestry of images unmatched by any other artist. His songs span everything in life from natural disasters to lost love – all intertwined with his personal experiences.

Lightfoot’s song “Home From the Forest” was particularly poignant to me. Three years of living in Cabbagetown often took me through Allan Gardens and Moss Park, where the park benches were strewn with “old forgotten soldiers.” I knew those old forgotten soldiers. I encountered them sleeping on the streets and slumped in the alleyways every day. The rooming houses and the haunted faces of their residents were perfectly depicted in the song. He brought our attention to our war veterans and to post traumatic stress disorder long before it was understood or acknowledged. With the magic only Lightfoot possessed, he honoured them.

The “dawn will come no more” for this truly magnificent Canadian icon, but he is by no means an old forgotten soldier. Gordon Lightfoot will live on forever through his music and will be revered as one of Canada’s greatest songwriters.

Story by:

Roger Thomas

Photography by:

Roger Thomas