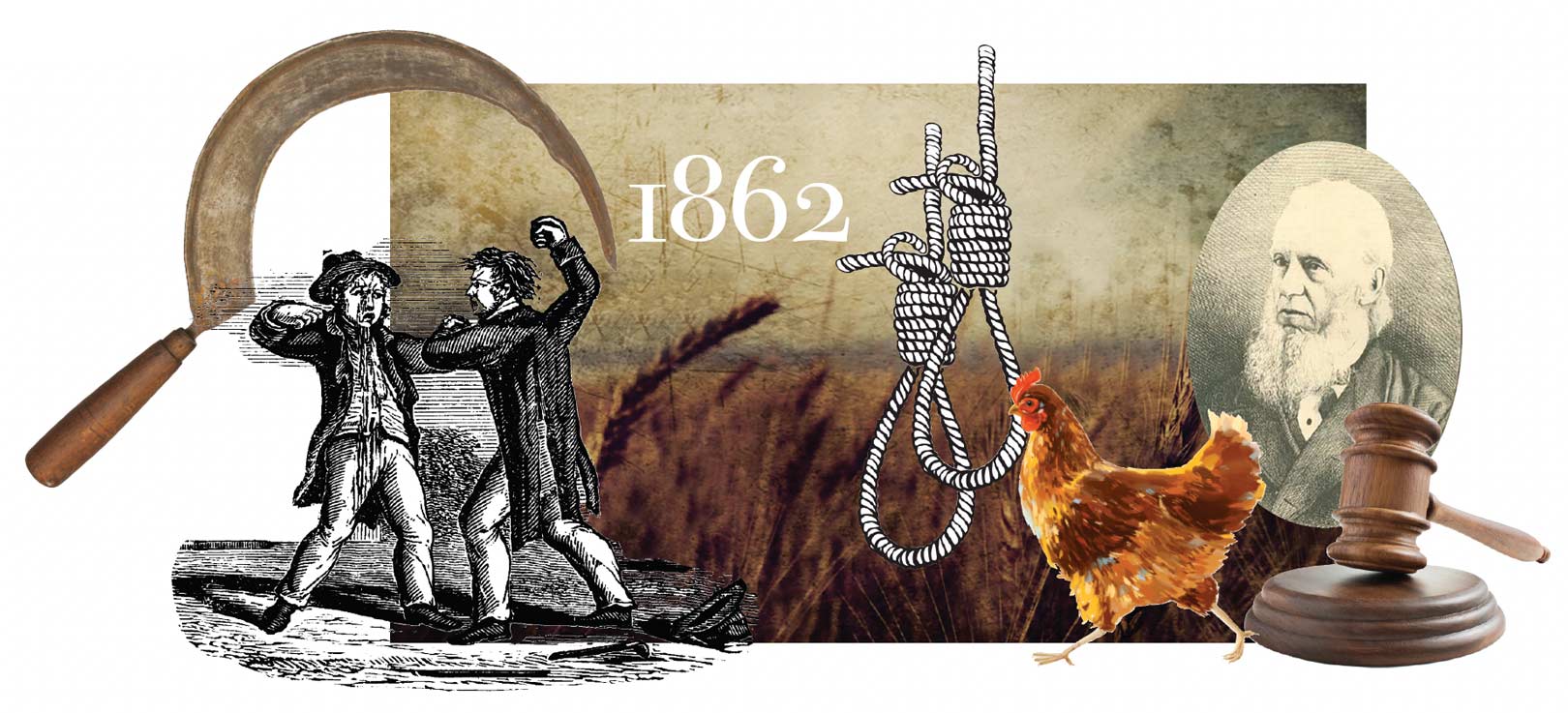

In 1862, a squabble over a missing chicken led to the first and only double hanging in Hastings County history.

From the start, Mary and Richard Aylward didn’t get along with their neighbour, William Munro. It was a hardscrabble existence for homesteaders in northern Hastings County, but life was that much harder because of petty squabbles and ill feelings between neighbours. Court records don’t reveal the origin of the across-the-road animosity, but after about a year of threats and verbal abuse, things spun out of control when the Aylwards accused Munro of dumping a dead dog down their well and asking how the “soup” tasted. It all ended in tragedy with William Munro nearly dead from slash wounds to the head after a violent confrontation in the Aylwards’ wheat field; his son, Alexander, was shot and bleeding. When the elder Munro succumbed and died, both Mary and Richard were arrested for murder and thrown into jail in Belleville.

This would prove to be no ordinary murder case, because there was an added element to the story that triggered public debate. You see, the Aylwards were Irish Catholics and the Munros were Anglo- Protestants. Today, this distinction seems less relevant but in 19th century Ontario, religious factionalism was rampant, and anti-Catholic sentiment was widespread among the Protestant majority. In 1853, someone tried to burn down the Catholic church in Port Hope. A year later, vigilantes did their best to drive Catholic settlers from Cavan Township near Millbrook. So it was nothing out of the ordinary for William Munro to hurl insults at his Catholic neighbours. And when the Aylwards went to trial for his murder, the facts made little difference in public opinion. Indeed, the popular verdict was based more upon whose side you were on.

On that fateful day, Munro and his son had stormed over to the Aylward farm, eager to pick a fight over a missing chicken. Already exasperated that Munro’s flock routinely strayed into their newly planted wheat field, Mary and Richard admonished their neighbours to keep the birds on their side of the road and ordered them to go home. Munro refused to leave without his hen. As he and his son searched the Aylward farm in vain, Richard followed, shotgun in hand.

You can guess what happened next. Tempers boiling, Munro knocked the gun out of Richard’s hand, but Richard was also carrying a pistol. When Munro lunged at him, Richard turned toward Munro’s son and fired. Bleeding horribly from a gunshot wound to his back, Alexander scrambled to his feet and ran home. A battle of fists continued, but the melee wasn’t settled until Mrs. Aylward stepped in, a newly sharpened scythe – a hand-held sickle-like implement designed to cut hay – at the ready. With deliberate, urgent swipes, she slashed at Munro, causing a serious gash to the head and another to the arm. Like his son before him, Munro staggered home, bleeding profusely. Alexander survived; William died 12 days later.

The Aylwards’ trial lasted all of one day. By any standard, it was a botched job: evidence, namely Mary’s scythe and Richard’s shotgun, went missing; some witnesses failed to show up; others contradicted their own testimony. Worst of all, Mary repeatedly incriminated herself, bragging to other neighbours, “I did not mean to hit him on the head. I meant to hit him on the neck and cut his head off.” This alone was enough to seal her fate, but she felt confident that the sentence would be lenient, for after all, she was merely defending her husband from an unprovoked attack on her own property. Her lawyer suggested Mary had been driven to temporary insanity. Even so, it only took the jury, some of whom were Catholic, a mere two hours of deliberation to conclude that Mary and Richard were guilty. However, they recommended mercy.

The judge – Sir William Henry Draper, a former co-premier of the united provinces of Upper and Lower Canada – didn’t buy the insanity plea. “Taking this woman’s whole conduct through the whole case,” he informed the courtroom, “we find nothing but the most cold-blooded barbarity and not an act committed in the heat of passion.” He said he had no choice but to sentence Mary to death by hanging. He sentenced Richard to the same fate as well, even though he had not wielded the weapon that killed Munro.

The trial was reported across Upper and Lower Canada, and immediately the Catholic faction cried foul. Newspapers in Quebec railed against Draper, claiming he was unwilling to show mercy simply because of the Aylwards’ religion. Belleville’s parish priest circulated a petition pleading for mercy, but the judge didn’t budge. The verdict proved to be a conundrum for newly elected premier John Sandfield Macdonald, a rare Catholic leader in a majority Protestant caucus. Indeed, the Aylward case proved to be yet another irritant in the growing sectarian chasm that would dog Ontario politics for generations. (Consider this: Macdonald was Ontario’s only Catholic premier until Dalton McGuinty was elected in 2003.)

Richard Aylward, age 26, and Mary Aylward, age 23, were the first married couple to be hanged in Canada. Their execution was public and attracted a crowd of 5,000 spectators to the Belleville jail. They left three orphaned children, one a babe in arms.

Story by:

Tom Cruickshank