Alexis Burnett and his team of trackers;

Tracking 101

Field mouse, deer tracks, family of white-tailed deer

from left to right: the elusive fisher and its paw prints ; traces of a fox attack on a mouse; fox sniffing out rodents

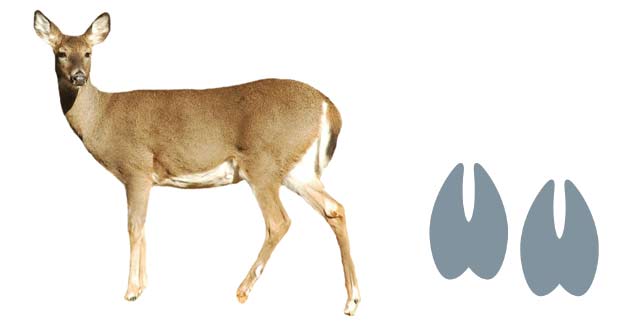

White-tailed deer

Mink

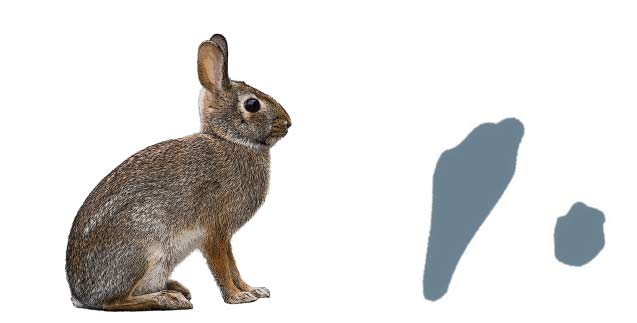

Cottontail rabbits

There’s more to tracking than just following tracks. An animal’s footprints can tell the story of how their day is going

Dusted by occasional snow flurries, our small group of eager adventurers huddled together in a winter forest. The forecast was for a temperature of -12°C, but we knew our wildlife tracking activities would soon warm us up.

Our leader was Alexis Burnett, who operates Earth Tracks, an outdoor school and canoe tripping company. He teaches the art of tracking in Algonquin Park and in natural areas near his home in rural Ontario. Alexis had invited me to join his group and I jumped at the opportunity. I wanted to learn about tracking from an expert.

On this quiet Sunday morning, we gathered around him as he outlined our objectives. Identifying the makers of those tracks would be one goal, but equally important would be going beyond mere identification to glean clues about the behaviour of the birds and animals that made them.

Sound is subdued in the winter woods. Birds call occasionally – the shrill cries of jays, the yankyank notes of foraging nuthatches, the cawing of crows and the chatter of chickadee troops bustling through the trees – but the overwhelming impression is quietude. This scarcity of sound may lead some to conclude that the winter forest is largely bereft of life, but an observant tracker can find its signature everywhere.

The woodland is a secret city, populated by creatures adept at concealment and active mainly after the sun sets. There is drama in this city, with animals and birds engaged in life and death struggles. The hunted among them slink and scurry, driven by the imperative to eat, while the hunters look and listen, alert to the sound of teeth gnawing on bark or a glimpse of furtive movement in the moonlight.

On this day, with the occasional cronk of ravens overhead, we found plenty of evidence of hidden life. We saw no deer, but their tracks were commonplace, and we found where some of them had bedded down in copses of cedar trees. There, encouraged by my smiling companions, I knelt down to smell deer pee. A revelation! As they had promised, the scent was pleasantly spicy, the distilled essence of cedar and balsam fir.

In a healthy ecosystem where deer abound, their predators do too, so we saw plenty of coyote tracks. Turkeys, ruffed grouse, weasels, squirrels and cottontails left their marks in the snow as well. The widely separated tracks of a bounding snowshoe hare spoke of fear. Spooked by something, it had darted towards the safety of a thicket.

We trekked up to the base of a cliff face where we found evidence that a heavy low-slung animal had plowed through the snow – a porcupine. These plodding rodents, protected by their passive weaponry of quills, are common forest dwellers in southern Ontario. For decades they enjoyed a kind of porcupine Shangri-La, gnawing tree bark to their hearts’ content and bothered only infrequently by the occasional hungry coyote.

But to the north, a porcupine nemesis was stirring. Large weasels called fishers, possessed of quicksilver movements and a unique porcupinekilling skillset, are on the move. Following their bristling quarry, fishers are now turning up in many locations south of their original Canadian Shield stronghold. In the Watershed area for example, fishers are seen near Port Hope and along the south shore of Prince Edward County. The porcupine’s brief tenure of peace has ended.

So on our hike it was no great surprise to find the tracks of this resurgent predator. Although we found no evidence of a porcupine kill, we did find the remains of a red squirrel near the fisher tracks. Perhaps the squirrel had satisfied the fisher’s hunger on this day.

“Learning to track has been a beautiful part of my growth as a human being,” Alexis says. “It’s not just about tracks, but about the behaviour, habits and the movements of the animals that made them. It’s about how animals interact not only with their own species, but with other species and with the plants, trees and the landscape itself.”

Alexis taught our group not only to be on the lookout for tracks but also to be keenly observant of anything else that may help flesh out ecological connections. These include scat, feathers, and bark stripped by teeth or antlers. On a second outing we followed the trail of a deer and discovered where it had shimmied under a fallen tree. Demonstrating the attention to detail that is a hallmark of good tracking, Alexis reached down and recovered a strand of hair snagged by the tree’s bark. He showed us how it kinked when bent, an identifying characteristic of the hollow hair of deer.

Listening to birds offers clues to the unfolding dramas of the woodland. This demands expertise – knowing what species is calling, and more challenging, interpreting their messages.

Ravens will advertise the location of a dead animal with a tumult of discordant calls, something to tune into when out in the field. If the animal is recently dead, the raven calls may serve to summon help. Wolves, coyotes and other predators will open up a carcass, allowing the ravens to feast.

Birds make alarm calls that radiate out like ripples from the position of a predator – a fox or a weasel perhaps – telling the wildlife community, and the savvy tracker, of the predator’s location. Trackers able to interpret this language can use it to guess what the predator is.

For instance, alarm calls that shout “weasel!” are scattered around, because weasels often move in an unpredictable manner over the landscape.

Foxes and coyotes on the other hand tend to travel in relatively straight paths, causing a “popcorn” alarm sequence according to Jon Young in What the Robin Knows. As a fox moves along a hedgerow for example, birds will “pop up” and voice alarms along its route.

Tracking then is more than simply following the footprints of animals. It is careful examination of other visual evidence and an awareness of the meaning of bird and animal vocalizations. With attention to such detail, predictions are made, scenarios are imagined, speculation is proffered, and credible stories are constructed. Story-making, the building of meaning, is one of the goals of tracking.

Alexis has plenty of stories to tell about his tracking adventures. One involved a ruffed grouse, a marten (another weasel family member, a little smaller than a fisher) and a wolf. They had followed a grouse through a forested area and all of a sudden came upon the bounding two-by-two tracks of a marten that had intercepted the grouse. Marks in the snow indicated that the marten was dragging the grouse. They then followed those marks to a sheltered alcove under the boughs of a balsam fir.

Alexis picks up the tale:

“There we encountered more tracks. Wolf tracks leading to the shelter. We hypothesized that the wolf took the grouse from the marten. Backtracking supported our guess. We found where the wolf had abruptly stopped and turned 90 degrees and then headed directly to the balsam fir to the marten and the grouse. The next day, about a mile away, we came across a fresh pile of wolf scat. We poked around and a grouse foot emerged. It may not have been from the same wolf, but very likely it was.”

The guesswork and hypothesizing involved in tracking have generated a fascinating proposition that the scientific method might owe its origins to tracking. Louis Liebenberg, author of The Art of Tracking, maintains that “to interpret tracks and signs trackers must project themselves into the position of the animal in order to create a hypothetical explanation of what the animal was doing.” With the hypothesis formulated, the trackers would gather evidence to support or disprove it, just like modern scientists do. Acting on a good hypothesis might allow a tracker to find an animal even in the absence of well-defined tracks.

Those who fail to think “scientifically” could go hungry.

Paul Rezendes in Tracking and the Art of Seeing supports Liebenberg’s idea: “At one time being able to read tracks and sign was a matter of life and death. Knowing where the food was and what the predators were doing could mean the difference between survival and extinction.”

After two days of tracking with the group, I headed into the forest on a solo venture. The trees sparkled in crystalline splendour from an ice storm earlier in the week. I would test my rudimentary tracking skills, attempt to think scientifically about my finds, and perhaps build a story or two of my own.

The trails of rabbits and mice, squirrels and shrews, and mink were etched in the snow. Signs of deer abounded. I found impressions of deer where they had rested under hemlock trees. Scat littered the snow. They had been feeding well.

Following one deer track, I measured a series of bounds approximately four metres apart. Like the snowshoe hare I’d come across before, I hypothesized that those great strides were powered by fear. And evidence of the probable source of that fear was easy to find.

Coyote tracks were abundant. I imagine a highstakes chess match plays out between deer and coyote in winter – move and counter move. With luck, healthy, fit deer avoid checkmate. A bad decision or ill health brought on by disease or old age tilts the board in the coyote’s favour.

The life and death struggle between deer and coyote shouldn’t be lamented. Paul Rezendes looks to moose and wolves to illustrate the benefits that accrue to both prey and predator: “… wolves continuously test the healthy and remove the weak, they shape the physical characteristics of their prey, leaving the healthier and stronger animals to breed. In turn, the moose challenge the wolves to become efficient and successful predators.” Both depend ultimately on the other for their well-being. Rezendes sees an “essential unity” between predator and prey.

This essential unity extends beyond the immediate predator and its prey, however, to include many other creatures. In southern Ontario, coyotes, foxes, weasels, fishers, ravens and a host of smaller creatures like shrews, mice and even chickadees feed on a deer carcass. Death begets life. Alexis refers to the sites where animals die as “wheels.” The spokes of these wheels, radiating outwards from the dead animal, are the tracks of the many animals that owe their lives to the deceased.

When exploring sites like these – in fact whenever he does any tracking at all – Alexis is conscious of how his presence may be affecting the animals he seeks to understand. While he loves to get close to animals, he draws a line when his actions might cause them undue anxiety and agitation. “When animals are aware of your presence,” he says, “you can see it in their behaviour, in their tracks. That’s when I say to myself, ‘enough’ and back off. The goal is not always to see the animal. It’s a special gift when you do, especially when they are engaging in their natural patterns, but for me it’s about the journey of learning on the trail.”

This observation articulates a dilemma all thinking naturalists struggle with. We want to connect with nature, with the animals, birds and plants, but we don’t want to hurt what we love. Respect, a key to healthy human interaction, must also prevail in our relationship with animals. The most treasured moments with animals are when they aren’t aware of us, when we are able to watch them interact naturally with their environment. Such encounters are deeply satisfying.

And in the final analysis, if encountering animals through outdoor pursuits like tracking is good for us, the animals can benefit as well. Understanding the “other,” whether among our fellow human beings, or fellow animals, helps build bridges and leads us to value other lives. Paul Rezendes says that “Ultimately, tracking an animal makes us sensitive to it – a bond is formed, and intimacy develops.”

For Alexis Burnett, tracking is a way to help connect people in a deep and powerful way to nature. “With tracking, you develop a real empathy for the land and for all the creatures that are out there.”

Tracking reveals this wealth of unseen animal life around us. And when we realize we share the environ – ment with so many other lives and we tell the stories of those lives, empathy follows. Tracking connects us physically and emotionally to the wild.

Tracking 101

Gear: Warm clothing, measuring tape and a small ruler for determining track size and stride length. A tracking resource is, of course, essential. The Lone Pine book, Animal Tracks of Ontario by Ian Sheldon is comprehensive, and it fits in a pocket. Google “tracking books” to find other excellent in-depth guides. Tracking apps such as MyNature Animal Tracks are available now as well.

When to Look: Any time there is snow on the ground. Morning after a light snowfall the day before is a great time to get out. Animals will have had a night to travel their territories and the tracks will be fresh. This will make them easier to identify. Fresh tracks also heighten the drama of tracking. You know the animal is near. Where to Look: To learn the tracks of common birds and mammals, your yard is a good place to start. Driveways, with their smooth surfaces, record precise imprints of tracks especially after a light dusting of snow. For a wider range of tracks however, and to immerse yourself into tracking Alexis-Burnett style, larger natural areas are required. In and near the Watershed region, forest tracts ideal for tracking include Ganaraska Forest, Northumberland Forest, Murray Marsh and Peter’s Woods Provincial Park, H.R. Frink Conservation Area and the MapleCross Coastline Reserve. Several of our larger Conservation Areas are also good tracking destinations. Pay attention to water features including marshes, lakes and streams. Mammals such as mink, beaver and muskrat are seldom found far from water.

Animals often use human trails for ease of movement and such trails can be good for basic track identification, if the trails are not heavily used by dogs and their walkers. However, if you want to learn the stories that tracks can reveal, bushwhacking is necessary.

Courses: For those of you inspired to take a deep dive into the world of tracking, Earth Tracks founder Alexis Burnett offers a wildlife tracking apprenticeship program. One weekend a month is devoted to intensive nature study and tracking. Earth Tracks also offers a variety of other outdoor experiences and workshops. Find out more at earthtracks.ca

THREE COMMON ANIMALS TO FOLLOW

White-tailed Deer

Deer are big and plentiful, making them excellent choices for a novice tracking adventure. When you find a deer track, first determine the direction of travel. The splayed hooves of deer taper to points at the front and are rounded to the rear. The pointed ends indicate the direction.

As you follow the tracks be on the lookout for deer signs. You’ll certainly find their scat or pellets – in winter little rounded cylinders usually less than an inch long. You may find where they have peed. If brave enough have a sniff. My guess is that, like me, you’ll find the scent pleasant!

Like us, deer need to rest, and following a trail long enough will likely lead you to a deer bed. Look for deer browse (leaves, twigs or buds) as well. Since deer have only bottom incisors, they leave rough cuts on twigs. They also scrape bark off young trees with their teeth, and in the fall, bucks will rub their antlers on saplings and trees, shredding bark.

Mink

Mink are seldom seen but live in almost every wetland in Watershed country. They are active through the winter and leave their tracks along riverbanks and the margins of ponds and lakes. They’ll also frequently venture onto ice. A trail that ends abruptly at a hole in the ice is likely that of a mink. Their tracks are often in twos, the front feet touching the ground together with the rear feet doing the same. Know though, that mink tracks can make other patterns as well.

Mink trails are a treat to follow. Sometimes a mink will dive into the snow, leaving an almost circular tunnel about 8 cm in diameter. On streambanks look for mink slides. Like otters, mink will slide on their bellies when slopes allow them to – undoubtedly an energy saver, but likely good fun as well! Mink scat is narrow and rope-like and even in winter reveals their aquatic foraging habits, often including fish scales and crayfish claws.

Cottontail rabbits

The distinctive tracks of cottontails, forming a roughly triangular pattern are familiar to just about everyone.

Cottontail scat is small and spherical, similar in appearance to Cocoa Puffs cereal. In winter, cottontails feed primarily on the twigs of small shrubs and trees (making them the bane of gardeners!) They snip those twigs at clean 45-degree angles in contrast to the ragged cuts deer make.

A popular misconception is that our rabbits dig holes for shelter and denning. European rabbits do, but not ours. Instead, cottontails shelter in dense tangles above ground and their tracks will usually lead to such protected retreats.

Story by:

Don Scallen