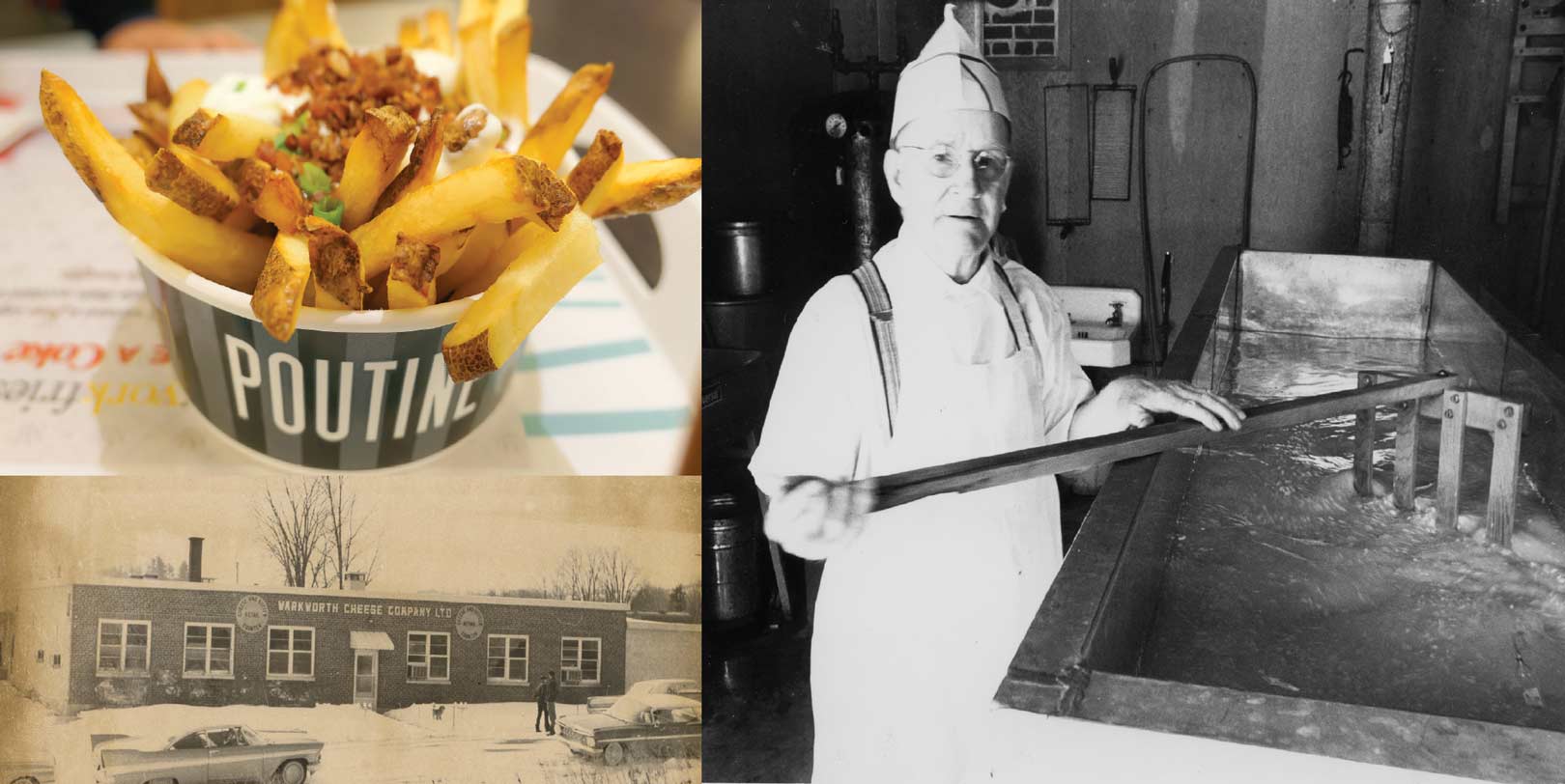

Award-winning poutine with curds; Warkworth Cheese Company c.1967, photo courtesy Northumberland County Archives and Museum

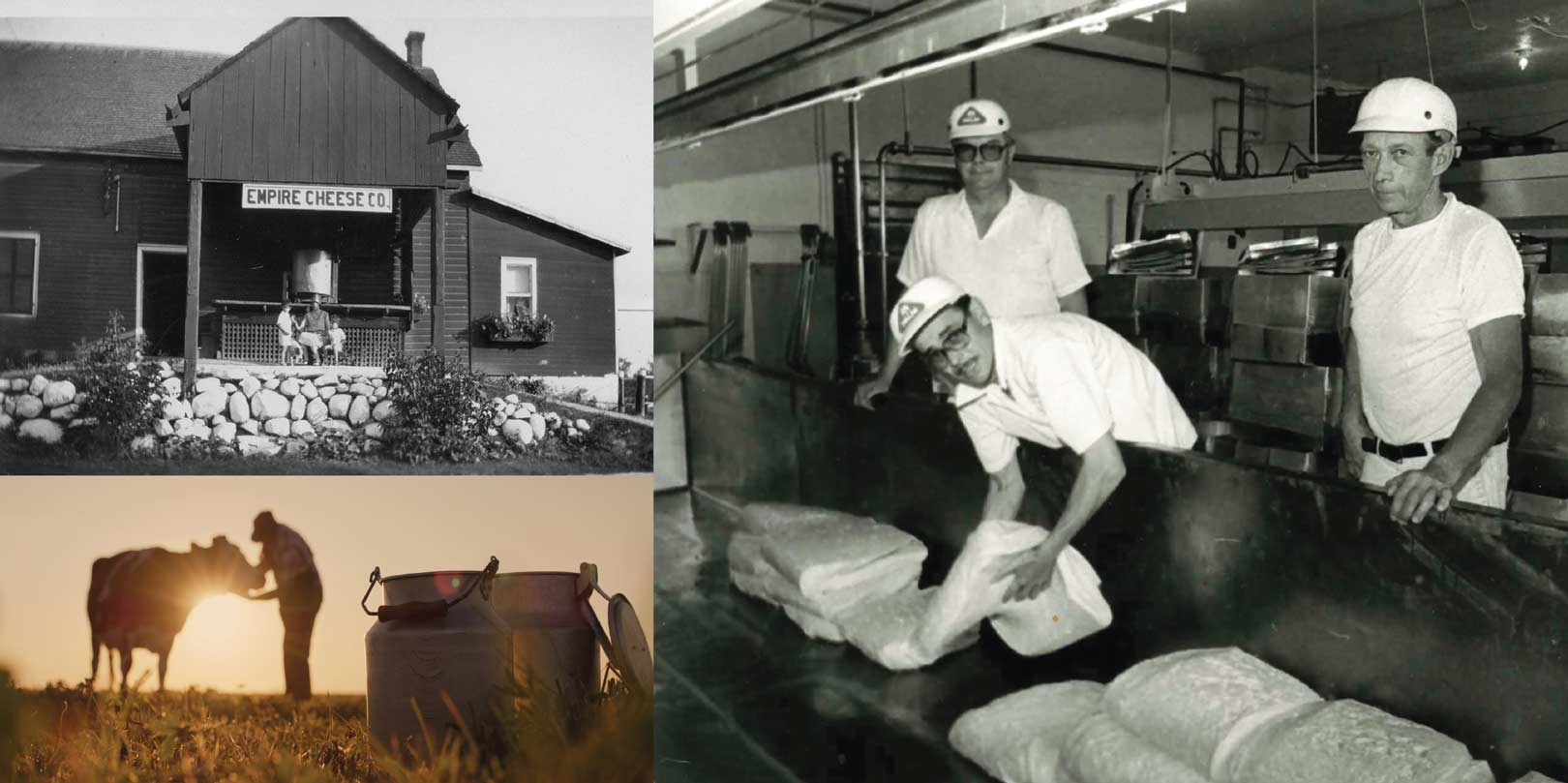

Left to right: Reg Barton demonstrating cheesemaking by hand at Warkworth Cheese Factory; Empire Cheese Factory 1933 – Bertha Haig Shillinglaw (Mother) with Maclean and Alexander (Children), photo courtesy Campbellford Seymour Heritage Society; Farmer with his dairy cattle; Empire Cheese Factory, Ken Mumby, Fernando Andre, Glen Anderson, photo courtesy Campbellford Seymour Heritage Society

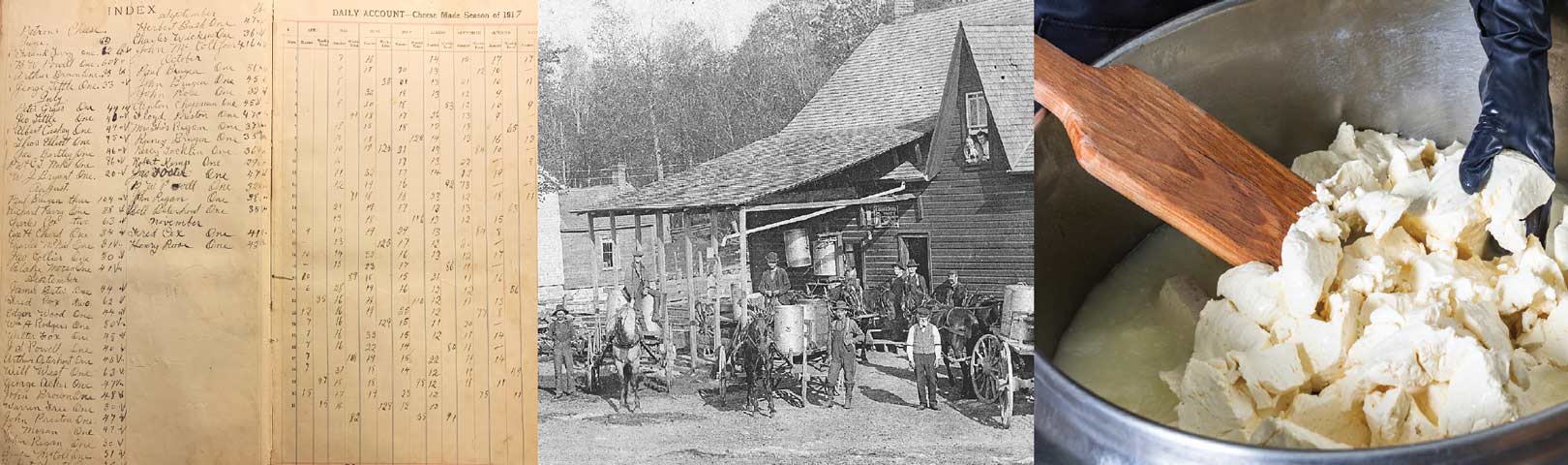

Left to right: Roger’s Cheese and Butter Co., photo courtesy Northumberland County Archives and Museum; Stanwood Cheese Factory c.1900, photo courtesy Campbellford Seymour Heritage Society; making of cheese curd

You may not know this, but our corner of the countryside was once a major player in the Canadian cheese industry.

At your next cocktail party, try impressing your friends with this interesting tidbit of trivia: Did you know that curds, the bits of curdled milk formed in the cheesemaking process, are the unexpected winners in the marketplace these days? “Curds account for 75 percent of our sales,” confides Kevin Larcombe, president of Empire Cheese in Campbellford.

Are you scratching your head over this one?

Kevin clears it all up with one word: poutine. In less than a generation, poutine has risen to exalted status in Canada, and as anyone worth their maple leaf knows, it is a hearty, delightfully satisfying, artery-clogging mélange of French fries, gravy and yes, cheese curds. Single-handedly, our national dish has injected new life into the Ontario cheese industry.

Long before poutine was on the radar, Empire Cheese had been in operation for over a hundred years. Founded in the 1870s, it remains an anomaly in today’s world of agri-food conglomerates. It survives as a small cheese factory that serves a regional market – say, from Toronto to Kingston, but concentrated in and around a loyal following in Campbellford – and functions with a handful of employees, including a master cheese-maker and two assistants. It produces just over 1,000 kilos of cheese in a five-day week – all cheddar – using traditional open-vat methods with no additives to boost yield.

“Our technique relies on the skills of the cheesemaker. It’s a real art,” Kevin explains, adding, “He has to monitor things like humidity and temperature to make a good, consistent product.” This is the traditional way to make cheese and holds great appeal to foodies, but hardly seems like the ideal business model for huge profits. Consider that the largest corporate factories can crank out 100 tonnes of cheese a day.

“We do it because we always have,” says Kevin, whose family dairy farm has been part of the Empire cooperative for three generations. “For us, cheesemaking isn’t driven by profits. It’s about supporting our families, doing a job that’s in our blood.”

Empire is the direct descendant of the type of cheese factory that once flourished in rural Ontario, particularly in our region, until relatively recently.

Eight dairy farmers hold all the shares in the Empire Cheese cooperative – they provide the milk, make the cheese and run the company.

By 1871 there were 325 cheese factories operating in Ontario, and about one-third of them were in Hastings, Prince Edward and Northumberland counties.

“You have to be a milker to be a maker,” quips Kevin. There used to be scores of cooperatives like Empire – at one time, there were over 100 cheese factories in Hastings County alone – but only a handful of independent cheese companies survive in our neck of the woods today: Maple Dale near Belleville and Wilton Cheese near Kingston come to mind. Several others, including Black Diamond and Ivanhoe, survive as brands, but have been absorbed by larger corporate dairies. Another cooperative, namely the Black River Cheese Co. in the southern reaches of Prince Edward County, recovered from a devastating fire in 2001, but was purchased by GayLea in 2016.

Everyone of the local cheese factories produced cheddar, which was a hard cheese that kept well, and more importantly, travelled well. The latter was crucial in establishing Canada’s world-wide reputation for fine cheddar, especially during two World Wars in which cheese production in mother England was virtually at a standstill. By then, cheese was our second largest export, after timber. We owe it all to some entrepreneurial dairymen from Oxford County in southwestern Ontario, who back in 1866 made a splash at the world expo in Britain with a giant wheel of cheese. At 7,300 pounds, it was one enormous chunk of cheddar and the whole world took notice.

At the time, the dairy industry was just gaining ground in Ontario, and it soon took over from wheat as the main occupation on the family farm. In those days before refrigeration, the focus was entirely on cheese because it is the least perishable of all dairy products. In 1867, there were already two cheese factories operating in Prince Edward County: one in Cherry Valley and a second in Bloomfield, both co-ops. Less than a decade later, they were joined by no fewer than 24 more in various rural County neighbourhoods.

The story was much the same in Quinte and Northumberland.

On his farm on Highway 2, just east of Port Hope, an enterprising and progressive farmer named John Wade opened a cheese factory about 1865. In the 1871 census, he reported that his operation carried on seven months a year and produced 28,000 pounds of cheese from 280,000 pounds of milk. Wade died a few years later, but there were plenty of other Northumberland and Quinte dairymen to follow his lead. In fact, the growth of the cheese industry was nothing short of meteoric. By 1871 there were 325 cheese factories operating in Ontario, and about one-third of them were in Hastings, Prince Edward and Northumberland counties. By 1906 – a peak year – there were even more: 94 in Hastings, 23 in Prince Edward and 44 in Northumberland. The region was second only to the southwestern Ontario dairy heartland in total cheese production.

Until the First World War, cattle had yet to be bred to give the barrels of milk year-round as they do today. Their milk supply was available for only a few months after the cows would “freshen” in the spring, finally giving milk after a lean, dry winter. But the problem of supply was nothing compared to the issue of spoilage, which dogged the cheese trade during its early years. In the heat of summer, milk would routinely go sour as it stood in tin cans awaiting pickup at the foot of the farmer’s driveway.

It was because of this very issue that factories were small rural operations, built close to the source of milk and remote from the urban markets in which the cheese would be sold. After all, farm milk could not be transported very far in the era before refrigeration, so for years, the economies of scale eluded the cheese industry. Indeed, the refrigerated tanker truck was the one innovation that changed the industry forever, for at last milk could be shipped in vast quantities, fresh from the farm to processing plants in the cities. Even so, cheese sales levelled off, thanks to increased demand for fluid milk and butter. Suddenly obsolete, the old rural cheese factories closed shop, one by one. Some saw the writing on the wall and sold out to larger dairies, while the Depression finished off others. By 1932, only 61 factories remained in operation in Hastings, 23 in Prince Edward County and 17 in Northumberland, and by the 1970s, only a handful of small producers remained. Today, virtually all Canadian supermarket cheese production is concentrated in the hands of four corporate foodstuffs companies; most of them are international conglomerates.

Currently, cheese production in Canada is on a roll. In a reversal of years past, butter and milk are declining while cheese consumption is trending upward: Statista.com estimated that we ate about 13.3 kg of cheese per person in 2021, compared to only 10.7 in 2005. Significantly, we routinely eat half again as much as Americans do – a reflection of the popularity of poutine, perhaps? Cheddar is still our cheese of choice, but specialty cheeses, as the industry calls them, such as mozzarella and Monterey Jack are fast rising in popularity. In all, Canada produced 523 million tonnes of cheese in 2019.

Along with our growing appetite for domestic cheddar and mozzarella, sales of imported gourmet cheese are also soaring. No surprise there, considering the current fervour for fine dining and homemade cookery that has inspired our newfound interest in locally produced food and artisanal fare. But there’s something missing here: You’d think the time would be right for an old-fashioned, craftsman-style revival of cheese-making here on home turf; but oddly enough, Canadian artisanal cheese hasn’t kept pace with other renaissance foods such as estate wine, organic vegetables or brew-pub beer.

Today, there are about 200 artisanal producers in the country, the vast majority in Quebec. There are only a dozen or so small factories in Ontario, although one pundit says the market could support up to 100. Despite lots of eager cheesemongers anxious to join the fray, the little guy is thwarted on several fronts: by the enormous overhead of setting up a spotless, state-of-the-art, regulations-ready factory; by the lack of college-level instruction in the art of cheese-making; and by the inflexible structure of the dairy industry, particularly the supply-management quota system. Designed in the 1960s to stabilize farmers’ incomes, the regulations make it difficult to buy milk directly from farms because all the quotas are either spoken for or prohibitively expensive. That’s why artisans often overlook cow’s milk altogether in favour of making cheese from sheep’s or goat’s milk, which are not subject to quota.

None of this seemed to matter to one entrepreneurial couple, who back in 2012, had a pivotal conversation over a bottle of wine at the Norman Hardie winery in the County. With no experience in cheese-making, Kelly Neals and his wife, Patricia Bertozzi, decided to put an offer on Fifth Town Cheese, the lone artisanal cheese company in Prince Edward County. Established in 2009, it was a valiant attempt to make its mark as a specialty cheesemaker, but had slid into receivership.

Kelly recalls, “With 30-odd years in her family’s food-importing business, it was a pretty good fit for Patricia. Besides, her grandfather back in Italy had been a cheesemaker. There was something romantic about carrying on an old family tradition.” So the deal was done.

Located near the eastern tip of what was once called Fifth Town (later North Marysburgh), Fifth Town Cheese is even smaller than Empire. They also make cheese in small batches, but their market is much more specialized and goes beyond typical cheddar. Indeed, these are exotic cheeses, some say an acquired taste: a triple-cream brie, an unpasteurized goat cheddar, a brush-rind farmhouse gouda, a truffle-infused tomme. “We make about 20 or 30 varieties, using cow’s milk, goat’s milk, sheep’s milk and water-buffalo’s milk,” Kelly explains. Most of it goes to gourmet food shops and upscale restaurants. A discerning clientele is taking notice.

Kelly recalls the early days of setting up their business. “Patricia’s background in the food business gave her a pretty good handle on marketing and distribution,” he says, “and for her, the best part has been creative experiments with new types of cheese and different flavour infusions.”

Sourcing the milk proved a challenge – who knew there was a water buffalo herd as close as Stirling? – but the one issue that continues to worry him is the lack of up-and-coming cheesemakers. Ben Holmes, Fifth Town’s current cheesemaker, who cut his teeth at the Black River cheese factory, gets high praise for his genuine devotion to his craft. He’s been at it for more than ten years now. Watching him work, surrounded by racks of ripening blocks of cheese, it’s not a stretch to think back to another era, when the rural cheesemaker was a more common sight. It’s a reminder of how important cheese has been to our local economy, and it makes us wonder if it just might be again.

The Origins of Cheese

Cheese may well have been discovered by accident. The story goes that 4,000 years ago, wandering nomads in the Middle East stumbled upon it when fresh milk was stored a little too long in a calf-gut bag. As the caravan jostled along its way, the milk was warmed by the sun, and thanks to an enzyme in the calf gut, it separated into two components: a liquid called whey (which is usually discarded) and a solid called curd, which is the basis of the cheese.

Cheese-making is a largely automated science today, but the ages-old principle remains valid. Instead of jostling on the back of a camel, the milk is constantly stirred and in lieu of the sun, it relies on being heated to a specific temperature. And the process still requires the calf gut – better known today by the more genteel moniker rennet – to coagulate the milk into curds and whey.

The vast difference in the taste and texture of various cheeses arises from adaptations in the cheesemaking process. Differences in water, fat and salt content result in an extraordinary range of firmness and taste, as does the length of time the cheese is aged and the conditions under which it is stored. But the single most important factor is the amount and type of bacteria used in its manufacture. It is the bacteria already present in the milk as well as those introduced during the process that make cheese such a memorable taste sensation. Never forget that fine cheese, like fine wine.

Story by:

Tom Cruickshank