The first big snowfall of the year began on the morning of the annual Christmas pageant at St. Ninian’s Church. At first just a few flakes fluttered wetly down from the sky, but it wasn’t long before the flurries thickened, and soon it seemed the air was more snow than not.

The snow collected until it covered everything: the hills, the trees, the sidewalks and lawns, and the nativity scene outside the church doors. Around noon, just as people were beginning to worry that it might turn into a real blizzard and force the cancellation of the pageant, it all tapered off, leaving the town muffled under a deep but manageable duvet of white. There was a collective sigh of relief; things were rattled enough with the historic New Year just a few weeks off. They didn’t need a crippling snowstorm too. By early evening most of the roads were plowed and sanded, and instead of silent snowflakes, the air was full of the sound of snow blowers in driveways and people calling to one another that it was beginning to look a lot like Christmas.

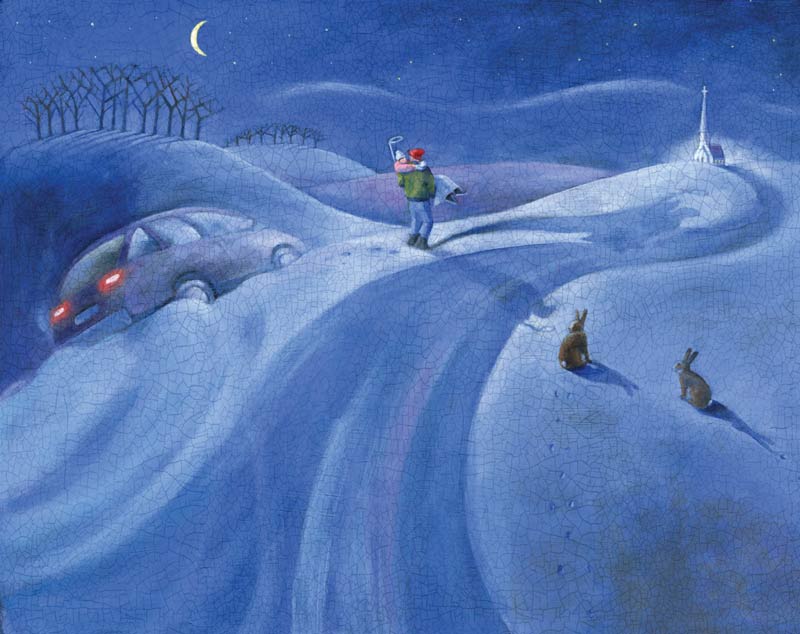

Just outside of town, in the deepening blue dusk, a pair of headlights lit the way for a smallish SUV moving slowly along a still-unplowed road. A father and his daughter were on their way to the church; she had to be there early because she was an angel in the St. Ninian’s pageant. The main angel, she’d been explaining to everyone. In a few hours the church would be full of seraphim, shepherds, wise men and of course Mary and Joseph with the Baby Jesus. The choir would be singing, and parents in the congregation – although asked not to – would be holding up their heavy video cameras to preserve the moment.

“Butch Vogan told me,” the girl was saying, “that the Angel Gabriel was a boy. That I couldn’t be it.” Her halo in its plastic headband wiggled back and forth as she talked. She had insisted on wearing it in the car. Her wings were prudently stored in the backseat.

“And what did you say back to Butch Vogan?”

“That angels aren’t boys or girls,” she replied. “They’re angels.”

He was turning to say “Good answer” to her when something on the road grabbed the steering wheel out of his hands and threw them sideways. He instinctively put a hand across to protect her.

“Daddy!” she screamed. There was a flash of road spinning past them, then a white wall of snow vaulted over the front of the car.

They sat for a quick moment, unable to imagine what had just happened.

“Are you all right?” he asked.

“We’re on the wrong side of the road,” she said.

The first reactions through ten-year-old eyes.

“Yes. It looks like we spun across. There must have been some ice.”

After a few tries to rock the car free, it became obvious that the rear tires were hopelessly stuck in the ditch. The car was going nowhere without a tow truck.

“You better call Mom,” she said.

Even without patting the pockets of his jacket, he knew that his phone was not there: it was on his desk at home. The plan had been to drop his daughter quickly at the church – normally a ten minute drive – and then head back to fetch his wife and son for the pageant at seven. He just couldn’t get used to carrying a portable cell phone with him, even though he’d had one for over a year. The convenience was almost too much: just flip the top and talk to anyone you wanted.

“Are we still going to get there in time?” she asked. He could hear her voice rising, as it did when she was trying not to cry.

“We sure are,” he said. “Not to worry.”

He came to a quick decision. They couldn’t stay there. It was too far to walk back home, but he could see the glow of the town lights just over the dark trees. It wasn’t more than a kilometre to the church, maybe less. In fact, it was probably the church’s floodlights that were causing most of the glow.

“I think the best thing to do is to hoof it.”

“What does that mean?”

“Go on foot. It’s not that far.”

“But what about me?” she asked. “The snow’s too deep…”

They both turned around to look behind them. Her wheelchair lay folded up on the back seat, with her Gabriel wings neatly beside it.

“Well how often do I get to carry my very own angel with me? We can send someone back for it when we get to the church. And maybe somebody will pick us up as we walk along.”

This would be a miracle in itself. The town’s streets, normally quiet after 7:00 p.m., were positively deserted on a Sunday evening in December. The only hope would be someone else heading for the church who might pass them.

“If we sit here we’ll get very cold.” Freeze, he meant, but did not say.

The accident had been two years ago but the images would play repeatedly in his mind forever: a toboggan careening down a hill; children all squealing with terrified fun; his daughter flying spreadeagled through the air as they went over a bump. The sound of her body colliding with the tree, instantly leaving no doubt as to which of them would come out the worse. In his dreams, time slowed almost to a standstill as he ran down to try to catch her in mid-air, never quite reaching her.

“And what about your bad back?” She liked to think she was taking care of him.

“Hasn’t bothered me in months,” he lied. Without thinking about what they had to do, he turned off the ignition and flipped on the four-way flashers. He wasn’t sure how long the headlights would keep shining, but they’d help as he and his daughter got themselves going. He climbed out his side of the car, and waded around to the passenger door. “All bundled up?” She zipped her parka over her white angel costume and put on her mitts. And straightened her halo.

As he picked her up, the lower back pain he lived with every day made its presence known like a hot knife. Not tonight, he willed. Please. Carrying her as a groom carries his new bride, as he had carried her so many times, he started walking down the road, leaving deep dark footprints. She wrapped her arms around his neck as he stepped through the drifts. The car’s headlights illuminated them from behind, creating a horror-movie shadow in front of them on the snow. Then suddenly they blinked off.

I can’t do this. The thought came to him in the cold darkness and filled him with a desire to just sit down at the side of the road. But his daughter must be cold already – she couldn’t move her legs to keep warm. He clutched her tighter and started talking to distract them both.

“Just think. In a little while you’ll be wheeling into the chancel to lead the other angels to the manger.”

There had blessedly been no reaction at all to a girl in a wheelchair playing the Angel Gabriel, announcing the upcoming birth to Mary, placating a puzzled Joseph, and presiding over the singing choir of angels. The appropriate ramps and approaches had been built and installed without a word.

“What’s a manger anyway?” She wanted to distract them too. This apple had not fallen far.

“A place in a stable where they put the hay for the animals to eat. From the French, manger.” He wasn’t actually sure of that, but she didn’t challenge him.

As they turned onto the wider county road, he hoped for a moment that someone might come along and save them. But hope was something that had taken a beating in past years; it wasn’t to be counted on. He did risk the tiny prayer that he wouldn’t trip and fall. Who’s the patron saint of people who can’t see their feet? he wondered.

This was the longest part of the walk, along the salty, slushy road. The wind was blowing wisps of snow off the tops of the plowed piles, sculpting drifts like little waves across the pavement’s edge. They were both quiet now. He thought about the new millennium that would be along in just a few days. Such a clean-looking number: 2000. He wondered if the new century would be neater than the shredded mess of the one they were just leaving. Will we be ruled by technology or will it save us? Will we fly to Mars? Will things like Christmas pageants survive, or will everyone discard even this outdated and irrelevant reminder of ancient mystery and hope?

About the time his shoes were caked with slush and his arms began to ache in unison with his back, they reached a sidewalk. He supposed he could go and ask for help in one of the dark houses behind the snow-blanketed lawns, if he could find one where it looked like anyone was home. That would likely take more energy than just continuing at this point. It wasn’t far to the church now, but he needed to rest or his back would fail them both. He stopped suddenly in front of the snow-covered front lawn that sloped upward toward the local art gallery.

“I need to rest a moment. You can sit on my knee.”

“No, just put me down on the ground for a minute.”

He placed her in the soft snow, arranging her legs in what knew was a comfortable position, and then lowered himself down beside her. The cold felt soothing on his fiery back. He knew if he stayed here too long he wouldn’t want to get up again.

Looking over at her, he had a sudden memory of her pale face looking up at him from the snow after the accident. She’d been in shock, unable or unwilling to tell him that she couldn’t move her legs. As they strapped her to the backboard her stoicism shattered him.

Of all of them, she had taken everything most in stride, learning what she had to do to deal with things, refusing an electric wheelchair, wanting to propel herself around. They’d moved to the new house last year after having converted it for accessibility. Ramps or not, it was a beautiful home, surrounded by forest, the perfect place to be a kid. Soon after they’d moved in, she and her little brother had convinced him to string Christmas lights in the giant old pine tree in the front yard. This year the acrobatic climb through the twisted limbs had nearly done him in, and he wasn’t sure how many more years he’d be able to keep it up.

Above them, the clouds had blown away and he could see stars. “I am an angel in the pageant,” he sang to the sky. “So get me to the church on time!”

“Daddy!”

“We can make angels,” he said swishing his arms and legs out sideways in the snow

“But I can’t make the bottom part.”

“Angels don’t need legs. They have wings.”

She swished her arms. “If I really had wings I wouldn’t need legs. I could just fly everywhere.” They were quiet a moment. Maybe someday you will, he thought.

“Do you think I’ll ever be able to walk again?” She had not asked him this for a very long time.

Some spinal injuries don’t reveal themselves all at once. Hers, involving two crushed vertebrae – one thoracic and one lumbar – hadn’t told their whole story at the start, so there was always some question as to the extent and possible duration of the paralysis. They’d had to wait and see what would regenerate on its own, or if anything would. Or if she might be in the wheelchair forever. They had agreed as a family never to say that word – forever.

“I’ll just say this,” he began, a hoarseness in his voice. “If you ever had to have an injury like this, you are living in the very best time in all of history to have it looked after.”

“Except in the miracle times,” she said.

He sat up, scooping her into his aching arms as he stood. They began walking again.

“How do you mean?”

“This other angel, Carly van Fleet? She was telling me about how Jesus helped a crippled man walk again. They had miracles back in those days.”

“And have you been thinking about that?”

“A little. Well, not really. I think they are nice stories.”

“People tend to pick and choose the parts they want to believe.”

“Like Santa Claus?”

“Yes, like that.”

Through the bare trees the very top of the church steeple was visible ahead of them, brilliantly lit. “It’s a bit like the Christmas star,” she said.

“Are you making a wish?”

“Maybe,” she said simply. Her capacity for wishing was pretty used up, he imagined.

Her legs swung as they walked. He leaned backwards, trying to brace his failing back. The verdict was in: She was officially too big now to be carried by him like this. He started to sing again.

“Where the snow lay round about! Deep and crisp and even…”

“I used to think it was Good King ‘Wences’ last looked out,” she said, tightening her clasp around his neck. Her arms had gotten very strong in the past two years, but she must be stiff and sore too by now.

“Lots of people still think that.”

“What’s the Feast of Stephen?”

“It happens on Boxing Day.”

“Why do they call it Boxing Day?”

“Because that’s when we clean up all the boxes.”

“Daddy!”

He knew the day was coming when she would no longer believe he had the answer to everything. It’s what children do; and what parents do too. We pull apart, our paths diverge, and we remain joined by something less tangible, but maybe more durable. One last time he hoisted her up against his chest and willed his leaden legs and his burning arms to hold the two of them up just a little longer.

The floodlit tower and steeple of the church came into sight above them like a snow-white beacon as they rounded the last corner. As they trudged up the steep sidewalk and the last of his strength was ebbing away, he could have sworn he felt her becoming lighter in his arms; it was almost as though she was carrying him.

He sank onto the bench next to the snow-crested nativity on the church lawn, putting her beside him. Amazingly, her halo was still in place.

“Take the night off, guys,” he gasped at the floodlit figures in the stable. “I’ve brought the real thing.”

Now I can stop. It’s done.

“Thanks for the lift,” his daughter said brightly. Then more quietly, “Dad.” It sounded as if she was trying the word out.

One last time he gathered her in his arms and they headed together up the stone steps to the church door.

Story by:

Chris Cameron

Illustration by:

Shelagh Armstrong