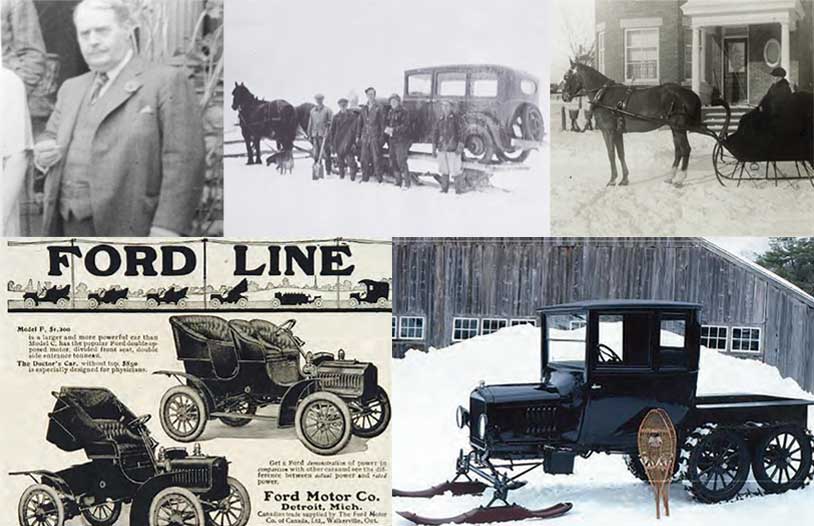

Clockwise: Dr. William Hayden; When all else fails, bring out the horses; a doctor making a house call in his horse and cutter; The Model T Snowmobile patented in 1922; An ad for Ford's specially designed Doctor's Car;

Whether it was by horse and sleigh, by Model T, or by a newfangled contraption called a Snowmobile, country doctors made their rounds.

Surely one of the most reassuring sounds on a wintry night is the rumble of the township snowplow passing down the concession road. With its blue light flashing and snow swirling in its wake, the snowplow offers hope that you’ll be able to get out and get on with the next day.

But a hundred years ago, conditions were a far cry from what you would expect today. Roads were often blocked for days and only made passable by the occasional plow. If you were a local doctor, the rural population whose lives depended on your skills, hoped, indeed prayed, that you would brave the winter conditions and come to their rescue.

In the still of the night, you might hear the whinny of a horse followed by a frantic pounding on the door: “Please, Doc, can you get out of bed and help me? The missus is about to have a baby.”

Oh, no. You’d finally fallen into bed after a 16- hour stretch delivering a baby – and it had been a hard birth. But now, another child was about to be born. Its life could depend on you.

And so, duty called. You’d pull on your long underwear, button up your shirt, grab your doctor’s bag, and head out into the dark in your trusty Ford, praying that the roads were clear. They all seemed to be Fords, these doctors’ cars. And coupes, too. Doctors’ coupes.

In the 1920s, a Model T Ford cost $350. For an additional $400 you could mount skis on the front in place of the wheels and rear-mounted tracks to replace the rear wheels.

FORD MODEL T COUPES were very popular vehicles among doctors in the 1920s. They were reliable on the rutted roads of the time, they would usually start, and they could be repaired almost anywhere fairly easily. “The doctor’s coupe,” as it became known, was a two-seater, with no back seat; but it carried a big trunk on the back – it even looked like a trunk – if the doctor needed extra accessories. Like a bedroll and extra clothing in case their outing turned into a sleepover.

Before the invention of automobiles, doctors got around in a horse-drawn carriage in summer, or a horse-drawn cutter, a small sleigh, in winter. Muddy, rutted roads were barely passable in spring and almost impossible in winter. Or doctors rode horseback, nodding hello on the trail to the various religious circuit riders they might encounter.

The selfless nature of doctors in the old days has been documented over and over again. Dr. George Goldstone came to Canada in 1835 and settled in Cobourg. Born in Bath, England, in 1806 and trained at the Edinburgh Medical School, he seemed undaunted by the wilderness of Upper Canada.

His training at Edinburgh to practise medicine in Canada was not unusual. You couldn’t practise medicine without a licence in Canada, and in the early 19th century, there were no medical schools in the country. The Edinburgh school, with its fine reputation, fit the bill. Even many Americans with a Scottish heritage studied at Edinburgh to practise in the United States. Canadians could gain access to the medical world by apprenticeship to an established doctor who had studied at Edinburgh, but they would have a better chance of success if they went directly to Scotland for their training. (The first medical school in Canada was the Montreal Medical Institution, which opened in 1824 and five years later became the Faculty of Medicine at McGill University.)

Goldstone practised medicine in Cobourg from 1835 to 1862, gaining a reputation as a pioneer doctor. He was one of those who spent many hours travelling through the vast and silent wilderness. In Cobourg Early Days and Modern Times, it was written, “He often times was called at midnight in winter to visit patients many miles away, whose homes lay in the midst of forests, far from neighbours or help of any kind, and far even from the beaten road. He frequently rode on horseback sixty miles a day, it being impossible to drive a carriage through the uncultivated country.” In the Rebellion of 1837, he served as medical officer with the Northumberland militia.

And yet, while spending much of his time on the trail, he kept up with modern trends in medicine. In the late 1840s, he was one of the first surgeons in the region to administer ether as a painkiller, even in “tooth drawing.” Goldstone retired to Quebec, where he died in 1872 and is buried in Cobourg.

Cobourg Early Days and Modern Times offers a similar view of Dr. William Hayden of Cobourg (1872-1950) who put in long hard hours running his rural practice. “He was never known to refuse a call in any weather or any hour.”

In later years, when combustion engines replaced horses, sometimes those cars just wouldn’t co-operate. A horse could always be coaxed to start. One blustery night, Dr. Roy Joliffe of Warkworth got a birthing call but his coupe wouldn’t start. So he walked to the township garage, persuaded the township road crew to fire up the road grader and take him to a farm where the farmer met him at the end of the lane with a team of horses and a stoneboat. He arrived in time to deliver the baby, then returned to Warkworth in the township snowplow. (Rolling Hills of Northumberland, 2000).

You have to appreciate that the country doctor’s hours in the last century in no way resemble the hours of medical practitioners today. Here was a typical day for Dr. Joliffe, as late as 1950: up at 5 a.m., meet patients for two hours, depart for his hours in Campbellford, seeing patients along the way. His afternoon office was open from 1 to 5 p.m., after which he would complete his charts for two hours. He then returned home to open his office for evening hours until 10 or 11 p.m. He recorded 800 births over 32 years, sometimes staying overnight in the hospital awaiting a series of births. His practice extended to Roseneath, Castleton, Colborne, Brighton and Rice Lake.

The reward? Maybe a dozen eggs, a bag of turnips, a freshly killed chicken.

A country doctor’s winter experiences could be quite extraordinary, even dangerous. But what could be more surrealistic than this experience: In the 1930s Dr. O. W. Anderson of Maynooth in north Hastings made his winter rounds in a horse and cutter. One day he had travelled from his home to Baptiste, about 20 miles away, where he delivered a baby before returning home – a very arduous journey. He was just sitting down to supper when he was interrupted by a knock on the door from two men who asked him to attend a sick woman in Sabine Township, about 15 miles further north. He protested that his horse was exhausted and so was he, and he couldn’t do it. However, they were burly railway men and they loaded him onto a railway handcar and pumped the jigger up into the hills. (A jigger is a track maintenance vehicle, in those days propelled by pumping by hand.) When he had attended to the woman, who direly needed his help, he said, “How do I get home?” The two men put him back on the handcar and gave it a push. The drop from Sabine to Maynooth over the 15 miles was about 200 feet, as steep as any railway incline in the Rockies. It was a bitterly cold night, but Dr. Anderson said the light of the full moon sparkling on the snow made it one of the most tranquil and interesting trips of his career. The only sound was the rumble of the steel wheels on the rails and, perhaps, the howling of wolves in the pine forests around him as he coasted home.

Not so lucky was Dr. Truman Beeman, a popular doctor in Bancroft in the 1920s. Driving his horse and cutter through a February blizzard on a house call in 1922, the cutter bogged down and got stuck. Dr. Beeman had no choice but to crawl through the snowdrifts to a farm near Paudash, west of Bancroft. Unfortunately, his noble effort cost him his life, for the poor fellow contracted pneumonia and died. He was described as a selfless, honourable man which he surely was. His funeral was the largest ever seen in Bancroft and funds raised as a memorial were used to purchase an operating table in the town’s first hospital. (These two stories are from the book North of 7 – and Proud of It!)

Before the advent of motor cars during the First World War years, road snow was packed down with huge heavy rollers, to give sleighs a smooth sliding surface. Through covered bridges, such as the one in Trenton, work crews might actually spread snow on the wooden road surface to keep the sleigh from coming to a crunching stop.

Doctors might often have two vehicles: a motor car for spring to fall, and a horse and cutter for the winter months. But keeping the winter horse in oats for the summer could be an expensive proposition.

Along came American entrepreneurs with a solution. “Can you afford to own and feed horses 12 months in the year simply for use during the winter season?” one ad asked. The obvious answer, was, of course not. Well, then… The Snowmobile Company offered to install a snowmobile attachment on Ford cars to make them as dependable in winter as in summer. The manufacturer claimed the machine could travel over two and a half feet of unbroken snow at an average speed of 18 miles per hour.

Virgil D. White, a Ford dealer in Ossipee, New Hampshire, received a patent designed to convert a Model T into a Snowmobile, a name he coined and trademarked. He put it on the market in 1922, selling the attachments exclusively through Ford dealers. Skis were mounted on the front in place of wheels, and rear-mounted tracks replaced the rear wheels.

They weren’t cheap, even by 1920s’ standards. An ordinary Ford coupe could be had for $350 (U.S.) but the ski attachments cost another $400. The company boasted that the Snowmobile was “an indispensable convenience for the person requiring rapid dependable transport in all kinds of weather.” Country doctors and rural mail carriers were the largest users of this type of vehicle. Fire departments, school bus and taxi drivers, grocers, milkmen and truckers also used them.

Needless to say, the conversion was not done quickly in the Doc’s driveway in October. It might be in Charley’s garage for a day or two. (While re- searching this article, I received a flyer from the Canadian Automobile Association offering to change my snow tires in my driveway. Wonder if they do these snowmobile contraptions?)

Time has moved on; most of the people who were born thanks to the help of an automotive snowmobile are gone, but some of those mechanical devices still live. Tom McCauley of Trenton found one abandoned in a farmer’s field near Frankford, with a tree growing right up through the tracks. The 1927 Model T Roadster was a genuine doctor’s car, owned and operated by Dr. Dave McMullen. Dr. McMullen, it turned out, was the McCauley family’s own doctor. McMullen was a popular local doctor, and his Snowmobile was often a welcome sight on snow-blocked back roads in the 1930s, 1940s, even 1950s. Tom has maintained the doctor’s personal touch in his restoration. There’s an inscription on the door: “Dave McMullen M.D. Frankford Ontario.”

Finally, let me introduce you to Ron Fitch of Coboconk. Fitch is a Model T fanatic. He owns seven of them, three of them the original machine. They’ve never been reconditioned. And they all run. Guess what he’s doing now? He’s building, part by part, a Model T Snowmobile – from scratch. They’re hard to find, these Snowmobiles, so he’s building his own, using photographs as a guide.

Today the automotive snowmobile lives strictly in the dreams of the hobbyist. While its descendant, the personal snowmobile, is still used in remote areas by trained medical professionals, women in labour are driven to hospitals over well-plowed streets and highways to deliver their babies in the safe and comfortable surroundings of a modern hospital.

It’s all routine now. Once in a while a baby will be delivered in a snowbank by a police officer or a paramedic, and then that’s a news story.

Story by:

Orland French