We have no choice about leaving this life, but there are choices we can make as to how we leave it.

Life is about choices, about making the best of a range of options. Then one day we realize we can’t do everything we used to do: our mobility becomes shaky; our internal systems rebel; reality strikes us in the face when a doctor gives us news we would rather not hear. As we grow older, our worlds diminish in scope, and possibilities diminish along with them. Gradually we lose our freedom to choose.

But having fewer choices doesn’t mean we have none.

Let’s not fool ourselves: Getting old is rarely easy, and dying is even worse; they are never optional. But retaining some control through the choices we make can help prepare the path. The average age profile in the Watershed region shows that we are older here, with higher percentages of people over 65. Now is the time to talk about choices.

EVELYN’S STORY

At the age of 96, Evelyn Morgan had her life turned upside down. She’d been living contentedly and independently in the village of Haliburton, when she suddenly had to get out of her apartment after the building became uninhabitable due to a bedbug infestation. Her daughter Lorelyn and husband Barrie Wood stepped in, and Evelyn joined them in their house in Lakeport.

There was never a formal plan to provide permanent accommodation for her mother, but Lorelyn says the family had always agreed that “if it ever came to the point where Mom needed to be somewhere, it would be with us.” Their house became Evelyn’s home. “When Covid hit, we were glad she was here. If she had stayed in her apartment she would have been totally locked down.” Fortunately, their own family doctor agreed to take Evelyn on as a patient, but noted, “She is going to live with you until she dies.” “It was the first time we’d thought of it that way,” says Lorelyn.

Sure enough, Evelyn lived the rest of her life with them in their 200-year-old house, surrounded by growing things and buzzing bees. And it worked out well, although “Partly because we live in a rural environment in an old house, there were times when we all could have used a little more space,” Lorelyn says, smiling. As Evelyn’s health declined in the last months of her life, things became more challenging. “But I honestly have no regrets. I never thought, ‘I wish I hadn’t done this.’”

Their coordinator at Home and Community Care Support Services (now Ontario Health atHome) proved to be an invaluable help, and the services went beyond expectations, Lorelyn says. “We always had very caring people come to the house to help her and hang out with her.” There was even some continuity in the care Evelyn received: “The first person who ever came to care for her was also the last person in her final days.”

In the winter of her 101st year, Evelyn started losing her appetite and energy, and it was plain her time was near. The weekend before she died, the whole family gathered together with her – there was laughter and music and singing. And of course, there were tears. Lots of tears. In the end, it was about nothing more than Evelyn and her loved ones, and the peaceful beauty of her passing. “Who could ask for a better death?” Lorelyn recalls thinking. There is a lament heard these days among some caregivers of older relatives: I don’t want to end up like my parents. If you ask Lorelyn Morgan: “I’d be pretty damn glad.”

THE ULTIMATE CHOICE

On a summer morning in 2021, John Stubbs confided to Heather, his wife of 34 years, that he was experiencing some severe digestive issues. It felt serious enough that they decided to go to the Emergency Department. Within 24 hours, John was handed a diagnosis of aggressive stomach cancer. There was no chance of a cure or even treatment – except for a possibility of some radical and life affecting surgery. “Who wants that?” asks Heather bluntly. Both of them had always been adamant: “Don’t ever keep us alive on machines.” The couple did not hesitate, but began looking into MAiD – Medical Assistance in Dying.

“The day after the diagnosis I broached the subject,” says Heather Stubbs. “We had no idea how long John would have.” Had he ever considered ending his life on his own? “Let’s do it,” he said. The two of them had always abhorred the prospect of finishing out their earthly existence attached to tubes and wires. Both were spiritual people, and neither of them felt that the end of the body was the end of everything. For them there was only one acceptable choice.

Their palliative care doctor was Francesco Mulé, from Northumberland Hills Hospital (NHH). John and Heather adored him. “He came every Friday to see John and always told us the facts as they were.” They discussed MAiD from the start, but Dr. Mulé advised keeping that option on the back burner for the time being. “You will know when you’re ready,” he told them. In the meantime, John’s family could come and visit him.

John Stubbs knew precisely when he was ready. By September, even though he was lucid and ambulatory – still taking daily walks with the dog – he was eventually unable to keep down even a sip of water. One morning he said to Heather, “I think we should get this over with.” Two days later MAiD was provided to him at home in his own bed, with just his wife and the doctor by his side. “He was upbeat right to the end,” says Heather. “John’s personal dignity was very important to him, and he never had to go through the loss of that dignity. I have no regrets. None whatsoever.”

“A GOOD PLACE TO LIVE”

How are we to make sense of the world inhabited by the dying? Where they are going, we can’t follow – at least not right away. This uncertainty can be addressed by a hospice, a portal between this life and whatever is next. A hospice serves both the dying and the living at once, providing care and solace to both. In their last weeks, residents are helped to feel that the hospice is not just a waiting room, but a temporary home.

ED’S HOUSE

Sherry Gibson’s enthusiasm for her work is contagious. As Director of Hospice Services at Ed’s House in Cobourg, she shows off the strikingly beautiful modern building with pride. “When people arrive here, we want this to become their home away from home,” she says. She has worked for Community Care Northumberland since the 1990s and became project leader when the hospice was first planned and built.

Ed’s House is named after Ed Lorenz, one of the early community donors to help get the project underway. Originally there were six patient rooms, and four more were added this spring.

“You never get a second chance to support a person at the end of their life. We need to make sure they have the best we can give them.” SUSAN WALSH

Becca Orban is a Registered Nurse who is the Clinical Manager for Ed’s House and looks after admissions. Typically, a resident can stay anywhere from hours to weeks, she says, with the average stay being around 14 days. During the time they are there the hospice tries to provide a peaceful homelike atmosphere with everything they can offer. And that amounts to a lot: Cozy rooms for residents and families to gather and chat; a spa room, a café, a gourmet kitchen to prepare familiar food, and a large deck overlooking the gardens. There is original artwork and stained glass all around. Everything about the decor is life affirming.

When residents pass away, they leave through the front door, where the staff can say their goodbyes. The exception is the west-facing door in the multi-faith Spiritual Room, which has a special role: The sun sets in the west, marking the end of the day and symbolizing the end of life to many of the Indigenous residents at Ed’s House.

Providing community outreach is a vital part of Sharon Sbrocchi’s role. As Community Manager, she helps look after families in the area, often recommending clinical navigators to help people at home cope with the confusing channels of healthcare. “The system can be daunting if you’ve not encountered it,” she says. She works closely with hospitals as well as Ontario Health atHome to stay in touch with the community.

The staff at Ed’s House are especially proud of their volunteers. “They are often people who have gone through the experience,” says Sherry Gibson. She smiles when she mentions the hard-earned accreditation Ed’s House received from Hospice Palliative Care Ontario. And it’s well-deserved, she says: “We’ve got a great team of staff and volunteers and community support!”

THE BRIDGE

Nestled among the hills of Northumberland, The Bridge Hospice in Warkworth was founded to “take the sting out of death,” according to Pauline Faull, one of the visionaries who shepherded The Bridge into existence more than 15 years ago. In essence, it’s more about living than dying.

Although people come here to spend their last days, “It’s not a place where you give up,” says Kim Good, Executive Director of The Bridge Hospice Foundation. “The hospice is about reimagining palliative care.”

Everyone entering or leaving this place crosses the bridge that leads to the front door. When a resident dies, a special quilt is laid over them, a candle is lit and the staff and volunteers assemble to pay respects as the bridge is crossed one last time.

“Our name is a reference to all the bridges in our area, plus the metaphorical bridge between life and death,” says Alison Lane, who handles communications and donor stewardship. She has been with The Bridge since its early days, and she remembers the gap that existed in rural areas before hospice care was available. In those days there were fewer choices as people faced death: Nurses in the community could see the anguish of people dying alone on the farm or the stress of being sent far away from their families to a hospital, she says.

The concept of The Bridge was initially viewed with skepticism by some people in the community who had never heard of hospice care. “There was definitely pushback, partly based on people not understanding,” says Alison. But it wasn’t long before the welcoming, homelike facility – built entirely by volunteers – took its place as a main feature of Warkworth’s community. Fast forward since those early days, and “some of those original objectors have brought their family members to stay with us.”

When the first resident was admitted in June 2013, “It was all volunteer; we were complete novices,” she recalls. Finally in 2016, professional staff were hired.

Residents arrive from all over the region, and the average stay is 11 to 14 days, although this sometimes stretches to 30 days, says Becky Marskell, Executive Director of The Bridge. Do they ever have to turn anyone away? “Our goal is to make sure that everyone has the best care possible, so if we don’t have a bed, we reach out to other hospices. All the hospices support one another. We’re not in competition.”

“People think that it’s gloomy in here,” she adds, “but it’s really not. There’s also laughter.” The layout and decor of the building affirm her words and emphasize the upbeat atmosphere. It’s bright, homey and warm here: a good place to live.

PALLIATIVE CARE

Palliative and end-of-life care occupies a special place in the healthcare world. It is a holistic approach that deals with physical, emotional and spiritual needs and embraces not only the patient but their family – and even their community. It is for those diagnosed with a life-limiting situation and is aimed at providing patients with as much comfort, dignity and quality of life as is possible.

Although the choice of palliative care might be a difficult one, it is still a choice – made every day by patients, families and medical caregivers.

For every hospice resident, there can be up to five other people – family, friends or other loved ones – who are beneficiaries of the care.

“WE FOCUS ON LIVING”

“Requiring care at the end stage of life is not a failure of care,” says Dr. Francesco Mulé, who is head of the newly formed Division of Palliative and Supportive Care at NHH. Rather, he says, it is a redefinition of success, focusing on comfort and respect. “The dying process is scary; you live your whole life trying to avoid it. When I meet a patient who’s scared, we focus on living, not dying.” (Dr. Mulé was the palliative care physician for Heather and John Stubbs.)

Since opening its doors, NHH has had a dedicated Palliative Care Unit; it’s a service that is core to the hospital’s DNA. And now the model is expanding: NHH’s vision is that palliative and supportive care should also be available farther “upstream” in a patient’s journey, wherever they are being looked after in the hospital. This means every level of staff – from custodian to practitioner – could be involved on some level.

“We found that people were at the end of life in many different areas around the hospital,” says Susan Walsh, the hospital’s CEO, “so we needed to expand our expertise within the environment, while also increasing connectivity to other units in the hospital and the services and supports offered by our community partners. Palliative medicine will always be offered to any bed in this institution, and the care will be accessible to every patient.” When the new division was being designed, a team came together to propose broader education for all staff, she says.

Dr. Mulé points out that there is still some stigma in the community about end-of-life care, and part of his job is to help clarify the concept. “Society doesn’t embrace dying, even though it’s all around us,” he says. “We have to do a better job in talking about death as a component of life. I usually have to explain that no one is throwing in the towel.”

There has been an increasing awareness of the need for palliative care and hospitals like NHH are meeting that need. Of over 100,000 people who died in Ontario in 2017/18, about 63,000 received palliative care in their final year, a gain of 15 percent over six years.

As Susan Walsh says, “You never get a second chance to support a person at the end of their life. We need to make sure they have the best we can give them.”

“ATTENTION MUST BE PAID”

Dr. Graham Burke was in the trenches in the early days of palliative care, tending to patients in the 1980s who were suffering from AIDS – a terminal disease at the time. In 1996 he brought his wisdom and expertise to the County, taking on a pioneering role in the formation of palliative care programs – a novel idea, back when few were involved in the field. He helped establish the Prince Edward Palliative Care Association, which eventually became Hospice Prince Edward – today a three-bed facility that offers support and comfort for patients nearing the end of their life.

This spring, Dr. Burke was awarded the Dorothy Ley Award of Excellence by Hospice Palliative Care Ontario. The award recognizes outstanding achievement as well as efforts to advance and improve quality of hospice palliative care. “I am very honoured to receive this award,” Dr. Burke says simply. “We are a medical organization. Our work starts with a life-limiting diagnosis, and the components of our care include symptom and pain management. But the main focus is always helping people.”

Dr. Burke’s colleague, Registered Nurse Heather Campbell, who has a background in public health as well as palliative care, adds that one goal of this type of care is to manage what she calls the “emotional pain” that can present itself alongside physical symptoms; this pain too is real.

There is no denying the positive impact that a small but nurturing facility like Hospice Prince Edward can have, she points out, and not just for the patient. For every hospice resident, there can be up to five other people – family, friends or other loved ones – who are beneficiaries of the care. “The end of life,” Dr. Burke observes, “is as important as any other part. And attention must be paid.”

INTO THAT GOOD NIGHT

In the midst of life we are in death, as the prayer books remind us. Not one of us gets out alive. In many cases this inevitability involves losing our faculties or autonomy as we age, becoming shadows of the people we once were. And yet we are people, with lives that remain just as precious as anyone’s, deserving of attention and care and the best chances for a dignified and peaceful departure.

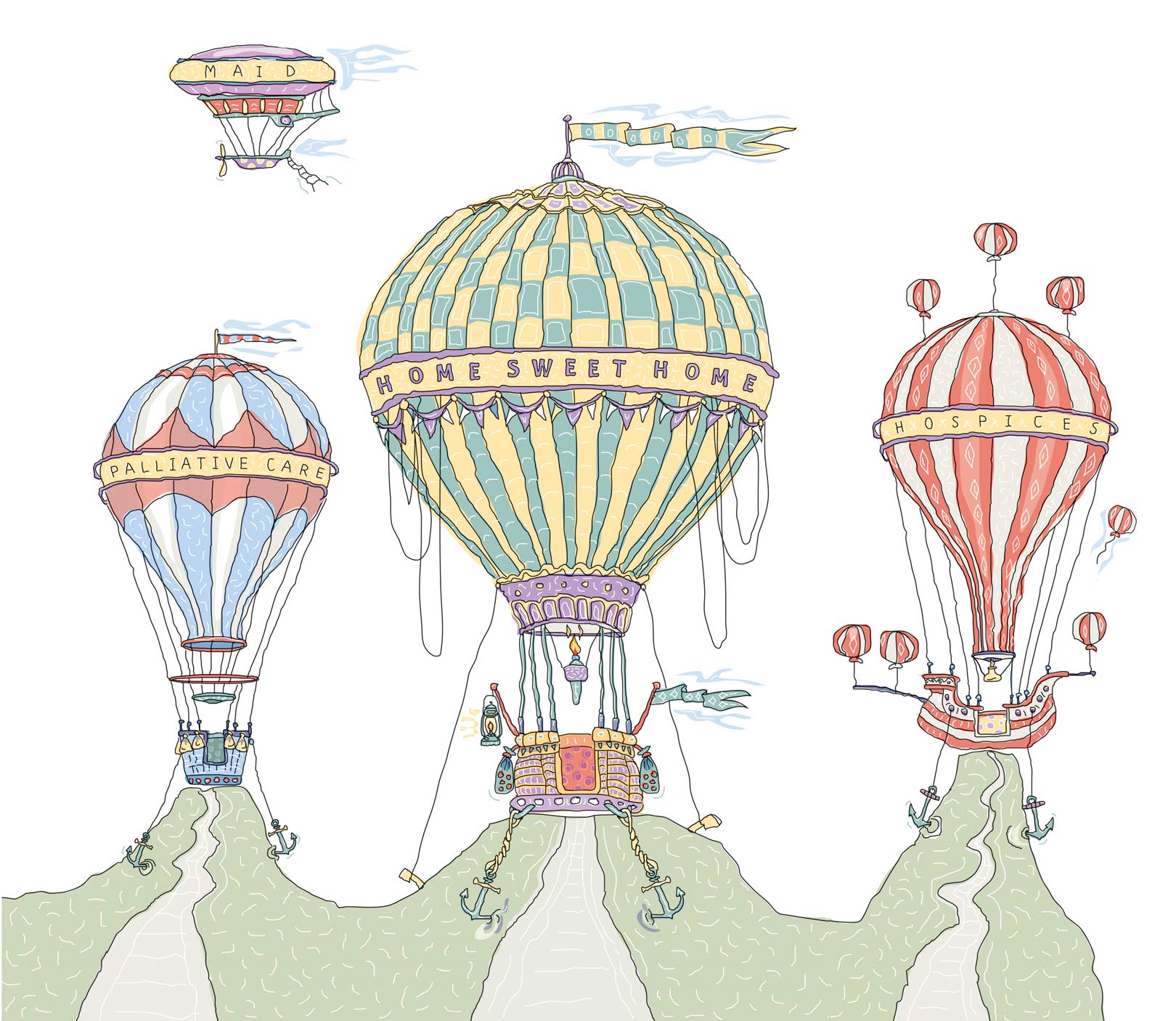

That departure can be made easier for some by palliative care or hospices; for others it will be a chance to stay at home; and for still others it will be a final exit under their own terms. In a situation where the end of the road is a certainty, it can be reassuring to know that there are choices along the way.

MAiD

If I cannot give consent to my own death, whose body is this? Who owns my life? SUE RODRIGUEZ

It’s important to note that if an MD had provided John Stubbs with MAiD ten years ago, that doctor might have been criminally charged with assisting a suicide. Since Sue Rodriguez’s groundbreaking, heartbreaking case in 1994, the right to die on one’s own terms has grown in scope and urgency as we all age and survive longer. Ms. Rodriguez, who suffered from one of the most devastating diseases there is – amyotrophic lateral sclerosis – took her request to die all the way to the Supreme Court. She lost the case, but in the end she was assisted by an anonymous doctor. Medical Assistance in Dying became a serious cause.

Since then, society has wrestled with the concept, both legally and ethically. Choosing the time and place to die offers an empowerment that might otherwise be taken away when illness has stolen control. But how and when a patient is competent to consent to the procedure has kept courts and hospitals busy.

The case that relaxed the legal reins on MAiD was Carter v Canada in 2015; the Supreme Court of Canada found that the criminal prohibition on physician-assisted death violated the Charter. Parliament passed a revised law the following year, giving Canadians the option to choose MAiD under specific circumstances.

One paradox that caused confusion was the fear some patients had that they would be too ill to grant final consent, which was mandatory immediately before MAiD was provided. Halifax resident Audrey Parker requested assisted dying earlier than she wanted to. Why? She couldn’t be sure she would have the ability to give final consent, and she called on federal lawmakers to amend the law. The “advance consent” amendment in Bill C-7 in 2021 was influenced by her advocacy (“Audrey’s Amendment” provides that if natural death is reasonably foreseeable, the requirement of consent immediately before the administration of MAiD can be waived).

All told, nearly 45,000 Canadians have chosen medical assistance in dying since it became legal in 2016. In 2022, there were 13,241 MAiD provisions reported in Canada.

POSTSCRIPT

A Journey Through Healthcare

Departures is the last article of our healthcare series, written by Christopher Cameron. We chatted about his observations and impressions when all was said and done.

Christopher spent the last six months visiting hospitals and hospices, meeting medical practitioners and family members, learning more about medicine than he ever expected, even though his father was a doctor (and Christopher thought he understood the medical world). He began with a deep dive into the critical nursing shortage that affects us all.

A FIERCE FLAME, Spring 2024

The nursing shortage in Ontario has reached the crisis point. Many nurses are at the end of their rope.

FACT: Ontario’s patient-to-nurse ratios are the worst in Canada.

Christopher: The article wasn’t intended to come up with solutions to the nursing shortages. I was interested in investigating what our local institutions were doing to alleviate the problem – here and now. I learned they are doing their absolute best to deal with the realities of the situations they face.

I was also astonished at how many young nursing grads are just thrown into the action without much orientation or practical training. It’s no wonder so many of them quit after just two years.

QUOTE: “It can be stressful when you don’t have all hands on deck; you go home feeling you didn’t do a good job that day.” Heather Campbell, Campbellford Memorial Hospital

PRESCRIPTION FOR CHANGE, Summer 2024

Finding a family doctor in our region is a frustrating and growing problem.

FACT: In Northumberland, Hastings and Prince Edward County there are up to 6,000 people without family physicians.

Christopher: While I was writing the article, I discovered that only 30% of last year’s Ontario medical school graduates went into family practice. Why? It seems that the paperwork and workload that come with the job are overwhelming and don’t match the payscale. I was told by several people that trained physicians should be working in areas of medicine where they can do the most good. I was amazed to learn more about the role that nurse practitioners play and their potential to shoulder much more of the burden of the family practitioners, who are sinking under their patient loads.

QUOTE: “We don’t need physicians caring for healthy people.” Nurse Practitioner Kathleen Foss

DEPARTURES, Fall 2024

None of us will get out of this life alive. It is crucial to learn what our choices are before we leave it.

FACT: The average age profile in the Watershed region shows that we are older here, with a higher percentage of people over 65.

Christopher: This article was an eye opener (a paradoxical thing to say about a topic on dying). As awkward as the topic is, people need to imagine how they want the end of their lives to unfold. I was also humbled by the respect and life-affirming attitude that the folks who worked at the hospices and the hospitals had for the people they cared for.

QUOTE: “The dying process is scary; you live your whole life trying to avoid it. When I meet a patient who’s scared, we focus on living, not dying.” Dr. Francesco Mulé, Northumberland Hills Hospital

FINAL THOUGHTS

Christopher: As I was leaving his clinic, palliative care specialist Dr. Graham Burke, who’s been practising medicine for 50 years, turned to me and said, “The end of life is as important as any other part. And attention must be paid.” Driving home from Picton that day, Dr. Burke’s words kept running through my head. That last sentence in particular. Ironically, it echoes a line spoken by Linda Loman in Death of a Salesman: “He’s a human being, and a terrible thing is happening to him. So attention must be paid.”

It came to me that Dr. Burke’s words could apply to all the healthcare articles that I had worked on over the last six months – and the countless conundrums they had tackled. Attention must be paid.

Story by:

Christopher Cameron

Illustration by:

Charles Bongers