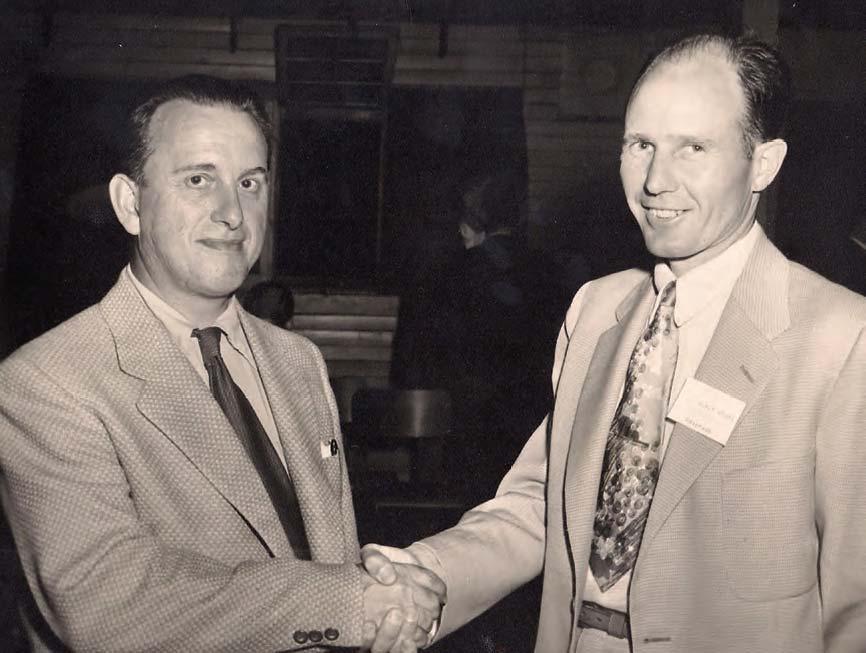

Foster M. Russell (left) welcomes a publishing colleague from Colorado to Cobourg in June 1954.

“Every story has three sides to it: yours, mine, and the facts.”

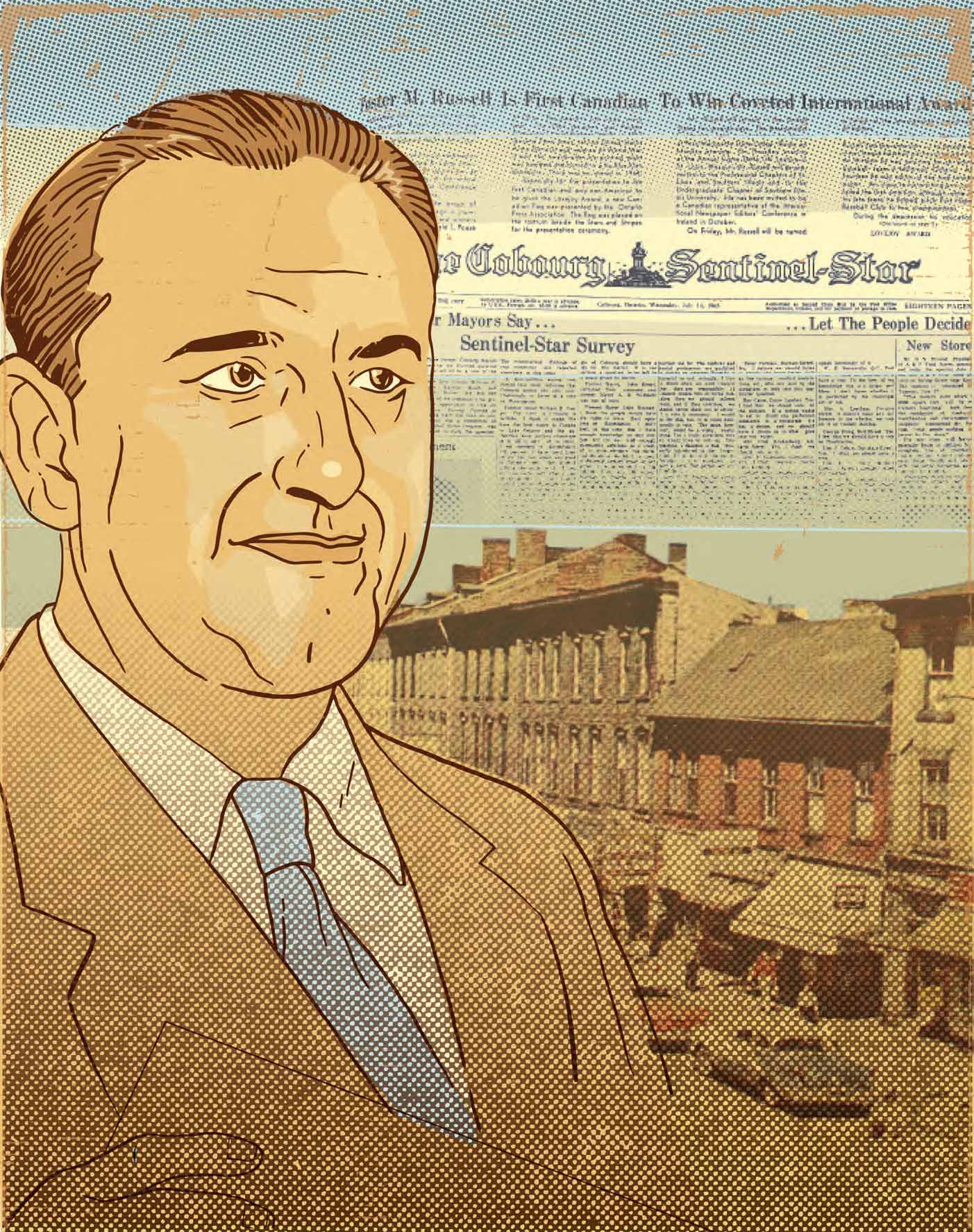

FOSTER M. RUSSELL

When they hanged Foster Russell in effigy in Port Hope on September 26, 1964, he did what any self-respecting journalist would do: he went back to his office and wrote an editorial. As owner and publisher of the Cobourg Sentinel-Star, Russell had come down on the wrong side of some union bosses who were attempting to organize the workers at a Port Hope factory. The fact was, he never minded coming down on the wrong side of anyone if it meant staying true to his convictions.

Fast forward to the journalism of today, which is pure gospel to its adherents and fake news to its opponents. There are no absolutes except bias. We search hard for newspaper people like Foster Russell.

“Every story has three sides to it,” Russell famously said. “Yours, mine, and the facts.” He made it his aim as a community journalist to publish the factual side, even if he usually added his own side in an editorial.

Russell bought the Cobourg Sentinel-Star on September 1, 1946. He put his editorial stamp on the newspaper right out of the starting gate. It would not be a weekly newspaper featuring weddings, funerals and ribbon-cutting ceremonies. It would be Cobourg’s news, good or bad, comforting or disturbing.

PRINTER’S DEVIL TO DEVIL’S ADVOCATE

You could say that Foster Meharry Russell was born with printer’s ink in his veins. His father Levi was the printer of the Millbrook Reporter in the early days of the twentieth century, and as a young boy Russell hand-turned the printing press. Years later, Levi worked the linotype at the Cobourg Sentinel- Star until Russell sold the paper in 1969.

Readers of Russell’s hard-hitting editorials in the 1950s and 60s might have been surprised to know that he was actually published as a poet in Toronto papers in the mid-1930s, sometimes using only his middle name, Meharry. One poem that appeared in the Mail and Empire (a few months before it became The Globe and Mail) began:

I can see beauty singing in the night, Her young sweet lyrics lifting to the skies, Her vernal gown bedecked in garlands bright, And youthful laughter leaping from her eyes.

After eight years as editor and publisher of the Coldwater News, Russell bought the Cobourg Sentinel- Star on September 1, 1946. He would remain at the helm through two lively decades, and he put his editorial stamp on the newspaper right out of the starting gate. One of his first big stories involved the prosecution of a local judge in an impaired driving case in which a woman had been injured. Russell was not concerned that the judge was a prominent local figure. This was news, and news was to be reported, even editorialized.

The tone was set for the Sentinel-Star. It would not be a weekly newspaper featuring weddings, funerals and ribbon-cutting ceremonies. It would be Cobourg’s news, good or bad, comforting or disturbing.

MOVING INTO THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

Foster Russell stood stolidly with one foot in Northumberland’s past and one in its future. He was an individualist and a conservative who believed in social justice and political truth; a traditionalist who sought to understand the crazy lifestyles and frazzled hairstyles of the hippie movement; a nononsense editorialist who also wrote poetry. To appreciate his story, we should take a moment to paint a faint backdrop of Cobourg in the mid-twentieth century.

Picture a small town with just a single stop light at Division and King, when the big news might have been the arrival of a new McDonald’s or the opening of Zellers. The church was the centre and moral compass of the community and every Sunday men wore suits and ties and women wore dresses and white gloves to attend.

Down at the lake, coal piles and oil drums around the deep-water harbour created a playground for young boys who rode their bikes to the top of the hills and slid down, blackening themselves and their clothes. The beach was not the pristine gathering place it later became. Winds often blew the coal dust over the sand, turning it sooty and grey. Before the St. Lawrence Seaway was opened and the water receded, the beach itself was smaller and the waves of the lake lapped at cement breakwater walls that are now on dry land.

In the harbour massive ships came and went, delivering and collecting cargo for Canada Wire and Cable or the oil companies. It would be many years before recreational boating took over the marina.

On misty evenings, people listened for the reassuring calls of the harbour’s fog horn. There was always Saturday night dancing to live music at the Pavilion in Victoria Park. And you could be kicked out of school for having long hair.

Life was good and the town was happy to be small and quiet. With typical irreverence, some teenagers referred to Cobourg as No-Burg.

One of those teenagers who had been invited to leave high school because of his long hair was Cobourg native and poet Wally Keeler. Russell hired Keeler right out of school to be the Sentinel- Star’s court reporter. The most important thing: make sure you spell their names right. Keeler remembers Russell as a mentor who was keenly interested in the youth of the 1960s. The two of them had many frank conversations about drugs, hippies, and hair length.

Although Russell could never bring himself to approve of recreational drug use – he saw it as similar to alcohol abuse – he didn’t believe anything was served by making criminals out of young people. He once visited some so-called hippies who had camped out on the Cobourg beach (somewhat to the concern of local residents). Later he wrote a positive account of his visit, pointing out how well they had cleaned up after their stay.

Wally Keeler recalls Russell as a journalist who would clamp onto an issue like a pit bull and who demanded focus and dedication from his employees. “When you say you’re going to do a job, you do the job,” he was known for declaring. He had little patience for employees who didn’t get this. Some didn’t last in the job.

CRUSADING AND CAMPAIGNING

Foster Russell’s long tenure as publisher and owner of the Cobourg Sentinel-Star would be marked by incisive editorials and strong, sometimes unpopular, political positions. Few readers were indifferent: they either loved or hated him. Right from the start, Russell made no secret of his distaste for socialism and his mistrust of labour unions. COMMUNISM ARRIVES IN COBOURG blared a 1948 headline when a union for electrical workers came to town:

“Wake up Cobourg and get rid of this communistic sown seed which has at long last come to your noble, quiet and peace-loving town… People look with envy upon Cobourg. Are we going to keep it this way, or allow a subversive element to destroy its priceless heritage and its honoured name?”

The leader of that union was literally run out of town by the workers.

In 1950, Russell was instrumental in a campaign to oust Cobourg’s mayor over a racist comment the mayor had made concerning a lease dispute for the dance pavilion. “Personally,” the mayor was reported to have said, “I would rather see a white man running the pavilion than a Greek… I want to see things in this country kept up to a white man’s standard.”

The paper’s reporting of these words – words that remain chilling 70 years later – plus Russell’s scathing editorials, led to the mayor’s resignation.

Russell was an old-school journalist, holding onto independence safeguarding the freedom to write what he thought. To show he even reported on his own trial for careless driving.

STRIKING A NERVE

The defining moment in Russell’s career came in 1964, during a strike at the Nicholson File Company in Port Hope. He took a stand against the United Steelworkers of America, which he felt was using bullying tactics to pressure employees who didn’t want to join the union.

The dispute became so hot that a crude dummy with a misspelled, hand-lettered sign identifying the effigy as Russell was strung up from the back of a truck outside the plant during a demonstration. This time it was Russell’s turn to be run out of town as he fled back to Cobourg after snapping a few pictures of the event. He said later that he felt lucky his wife Jean was sitting in their car with the engine running as a jeering mob came toward them. The whole thing reminded him of “a television cowboy show.” In a heartfelt, timeless editorial, he wrote “To be hanged for truth is to murder freedom. To deny opinion is to put in jail every Canadian’s outward expression of thought.”

The union more or less prevailed in the dispute, but the world took notice of Foster Russell. Newspapers, public figures and ordinary citizens wrote to support his dedication to reporting what he saw as the truth regardless of the consequences. In June 1965 he was awarded the Elijah Parish Lovejoy Award for courage in journalism by the International Conference of Weekly Newspaper Editors. It was one of the proudest moments of his life.

“NO ONE IS POOR WHO HAS EYES TO SEE”

Away from the newspaper, Russell immersed himself in many aspects of Northumberland life: He was a politician and school trustee, took active roles in the historical societies of Northumberland, and founded CHUC, the area’s first dawn-to-dusk 1000- watt radio station. He was even publicity director of an international plowing match.

Russell was an old-school journalist, holding onto independence like a pit bull and safeguarding the freedom to write what he thought. “Throughout an editorial career I have thrived on opinion,” he wrote. Often his views were unpopular and some seem hopelessly archaic today, but the notion that all views should have the chance to be expressed is universal and timeless. To show he held no favourites he once even reported on his own trial for careless driving.

He did not court advertisers with news they always wanted to read, and it’s possible the paper’s revenue suffered from this. Russell didn’t care. A rugged individualist, he believed that the only true poverty existed in the mind: “No one is poor who has eyes to see and ears to hear.”

Despite his disregard for popularity, the paper’s style attracted readers. He used the weekly format to create cliffhanger story endings each week so that readers would have to buy the next issue to learn what happened next. And buy they did. By 1968 the paper had a print run of 6,400 copies.

After Russell sold the Sentinel-Star in 1969, an editorial in the Campbellford Herald summed up his career:

“He has made a gigantic contribution to the field of journalism in Northumberland County and beyond in the cause of justice rights.”

He never retired, but shifted his talents to writing columns and pursuing his passions. He was instrumental in the project that restored Barnum House museum in Grafton, and in 1978 he was appointed to the panel of the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal.

In what must have been a scarce amount of spare time, he authored seven books. The most notable of these was a 1981 biography of Joseph Scriven, the nineteenth-century Port Hope resident who wrote the hymn What a Friend We Have in Jesus. In the book he maintains that Scriven could be considered the most famous man ever to live in Port Hope, even though few people had ever heard of him.

A word that keeps coming up in descriptions of Foster Russell is independence. This is reflected in his unwavering dedication to honesty in journalism, regardless of who it affected. He saw the news as a “mirror to the community,” and believed that it should all be told – good and bad.

There’s no question journalism today is guilty of the opposite. Many news outlets pander to loyal readers who support their editorial party line, and in turn those readers love having their biases confirmed. They are fed the online stories they want to read and attack not only opposing ideas but even the opposition’s right to hold them. Scruples such as Russell’s seem as old-fashioned as hot lead typesetting on a linotype machine.

The stories of Foster Russell’s life would fill a book – and have. In the last four years of his life he began to assemble an autobiography, which was published by his widow Jean and son Robin (a provincial politician) after he died in 1984.

“Perhaps my greatest desire in life has been to leave words behind me which will have something to say to human beings,” he wrote in the year before he died.

He may have been born with printer’s ink in his veins, but as the title of one of his books affirmed, Foster Russell lived his life with ink in his soul and indestructible conviction in his heart.

For more information: Foster Meharry Russell: The Life and Times of the Community Publisher

Thanks to Katie Kennedy, Northumberland County Archives; Lynn C. Bilton, Wally Keeler, Linda Hutsell-Manning, Maureen Mullally

Story by:

Chris Cameron

Illustration by:

Carl Wiens