The past year offered hope of a resettled life for Rosalia and Ivan. Now, sheltering in a country far removed from the Russian invasion of their homeland, the farming town of Calumet Falls offered refuge.

The couple had met as members of a symphony orchestra in Eastern Europe. Rosalia was a pianist, Ivan a second violinist. When war displaced the pair from their homeland, Ivan’s violin was saved, Rosalia’s piano was lost.

The ancient city where they had lived stood in stark contrast to Calumet Falls. Buildings of red and brown stone adorned the central square from where streets ran in separate directions; each had clothing shops, bakeries, and a butcher, shoemaker, hat maker or a tailor’s shop.

Within the centre was also a park where elders met and families with young children gathered daily. A great fountain rose in the air as songbirds collected on the branches of the old and towering oaks that touched the sky. Sounds from the skating rink in the winter spoke of joy, and on Sundays and moonlit nights, laughter and song mixed with the music.

The three-storey conservatory building with its inner courtyard and gardens nestled against the banks of the nearby river; in warmer months, the notes of cellos and French horns spilled through open windows onto the waterway below. The conservatory and orchestra were central to the world of Ivan and Rosalia until the peace was shattered and they had to flee.

Rosalia knit all day and into the evening; the clacking of the needles, the rhythm of the rocker, and the sounds of song from the upstairs flat seldom paused.

When they first arrived in Calumet Falls, Rosalia and Ivan were met by Catherine, the owner of John’s Barbershop, a landmark that had stood for generations on the main street, a business whose name never changed over decades of ownership. Catherine was also the driving force behind the local Ukrainian support group and offered the flat above her shop to the couple. Cleave, owner of the hardware store, Marge from the grocery store and neighbours like the Anderson family had pitched in to paint and set up the accommodation. Catherine donated her grandmother’s blue wooden rocking chair.

The tiny flat was made grand by its expanse of window overlooking the slow-moving Calumet River. Sadly, all that was left of their old world – where the earth, buildings and monuments of antiquity had been torn apart – was preserved in six salvaged photos that greeted Ivan and Rosalia each day from the wall at the top of the stairs.

The couple were now in a country, a region, a village where unfamiliar customs and languages created distances. It meant reimagining lives, relearning what was once familiar; everything that is, but the music. They understood how music bridged cultures. Although for now, Rosalia and Ivan knew they were a duet without a piano, their determination told them that somewhere, a piano sat waiting.

To fill the void of daily music practice, Rosalia took to knitting, something her grandmother had taught her. This kept her fingers nimble; the lanolin from wool soothed her skin. In the evenings, Ivan practised violin while Rosalia kept time from the rocking chair, singing the songs of old. With yarn over needle, she stitched one and purled two. Ivan found a job at the Riverside Dairy. The daily route to work took him by bike over the town bridges. Each time he crossed a bridge he moved farther from the world he’d left behind and closer to his future.

While Ivan was at work, Rosalia would take her bike and explore the countryside. One day she headed over the bridge and followed the Calumet River until she came to a woollen mill. Inside the grey limestone walls, she discovered a cacophony of colours, skeins upon skeins of wool – some heavy and some finely spun – piled high in wooden bins. The colours in the bins were finished with natural dyes, tints that enveloped her present world; scarlet from the high bush cranberry; sepia browns from the walnut trees; greens and blues and yellows from wildflowers.

While sifting through the skeins she met Sarah, a worker at the mill and the owner of a friendly face, who helped her sort through the textures and colours. Through glances, smiles and hand gestures, Rosalia learned that Sarah lived on a farm and kept horses. Sarah learned that Rosalia yearned for a piano so she could once again play duets with her beloved Ivan. On subsequent visits to the mill, their quiet friendship blossomed, and within a few weeks Rosalia returned with a pair of hand-knit mittens for Sarah as a gesture of thanks.

At the Riverside Dairy, Ivan began to study the wording of the packaging as the containers came down the line. This, he thought, was a practical way to improve his vocabulary. At the grocery store one day he enlisted Marge to help him pronounce a number of words; words like: old/fort cheese/fromage; milk/lait; butter/beurre and ice cream/crème glacée. With a smile, Marge pointed out how even locals found bilingual labels confusing sometimes.

When Ivan recounted his language adventure to Rosalia, it reminded them of how music knew no borders. The couple understood that when people couldn’t find a way to say how they felt, music would say it for them. Maybe not with words like butter/beurre, but with harmonies of happy or sad, playful or heavy. Music spoke in every language, whether it was a child’s song, an operetta, country ballad or anthem.

That week, Rosalia went downstairs to John’s Barber Shop for a hair trim. As she sat waiting, Catherine complimented the scarf and toque Rosalia was wearing. Rosalia said she had finished knitting them that morning. Customers joined in, praising the needlework and bright colours. Catherine suddenly had the idea that Rosalia could display her mittens and scarves in the shop window and sell them.

Word spread quickly throughout Calumet Falls, and soon the woollens began to sell. Rosalia knit all day and into the evening; the clacking of the needles, the rhythm of the rocker, and the sounds of song from the upstairs flat seldom paused.

Socks, mittens and scarves began to light up the barbershop window as Rosalia’s knitting attracted more attention and sales. Temperatures dropped and Rosalia could be seen riding over the bridge and along the Calumet as she biked to the mill again and again. Her dreams of music, she told Sarah, could come true. She might be able to afford a piano. Maybe even by Christmas.

In the evenings she knitted and sang while Ivan bowed his fiddle. As the season deepened and the air grew cold, garlands suspended in the barbershop window held rainbows of mittens that brightened the dark skies. The view from Rosalia’s window was now a scene from old, as hockey nets appeared on the Calumet and the clap of sticks and the thump of pucks echoed through the frigid air. Rosalia found a songbook in a thrift store; one song caught her fancy – a new tune with a familiar word: the khokey pisnya, the hockey song, with lyrics she made up as she went along – khokey night was khokey night wherever the game was played.

More sales at the barbershop meant long days and late nights for Rosalia and Ivan. They imagined how their former students at the conservatory would laugh at the concert pianist playing her knitting needles while her husband accompanied her on the violin.

It was a Saturday morning when Rosalia went to the hardware store and saw Cleave pinning a photo of a piano to the notice board. Cleave told her that it was for sale and belonged to some folks who lived just outside of town. Rosalia’s heart jumped. Cleave agreed to call about the piano that very same day.

Rosalia headed home in anticipation: would her knitting money be enough for the piano? An hour later, Cleave confirmed the price, and they counted their money. They were so close! Rosalia set to work again with renewed vigour. Downstairs in the barbershop Catherine heard the pace of the rocking chair and tempo of the violin music intensify. Rosalia’s hands grew stiff and her arms were sore; one by one the mittens, socks and scarves were delivered to the barbershop to be sold. At the end of the week, they counted the money again. Their eyes met and they realized that in spite of all the long hours and healthy sales, their dream was still out of reach. With a heavy heart, Rosalia told Cleave that they simply couldn’t afford the piano.

That evening, Rosalia swept the snow from her balcony. She then gathered a string of lights, and one by one, she tied each to the railing with a strand of bright wool, perhaps to ease the heartache over the lost piano or perhaps to soothe her longing for home. The lights of the barbershop joined the lights of Rosalia’s balcony, and together they lit up the night.

By the time she came inside; her spirits were low. That night the couple fell asleep holding one another, with dreams more dark than light.

Snow covered the hills; it drifted through the park and stuck to the arches of the bridge. Main Street was quiet. Christmas shoppers had gone home, and along the roads, families were asleep under rooftops and smoke climbed from chimneys. Winds from the north slipped through the pines and crested every hill.

The next morning, as snow fell harder, Catherine climbed the stairs to the flat to check on the couple. The silence of the rocker and the absence of song was a sign that all was not right. It wasn’t long before she heard the sad news.

Straightaway Catherine headed to the hardware store, where together she and Cleave put out the call: Marge, Sarah and the Anderson family all said they could help. That day word spread among the workers at the dairy and the woollen mill; by evening, money from the whole town was flowing across the bridges into the piano fund. A day later and just as shops were about to close for the holiday, Catherine held her breath and tallied the funds. Things were a go – if only the snow would let up!

Sarah called Catherine to say that while delivery by truck was impossible because of the snow, she owned two horses that could pull an old work sleigh they had at the farm. With the help of her dad, they would hitch the team and sleigh and pick up the men who would deliver the piano.

A horse-drawn sleigh was a sight seldom seen in Calumet Falls. Nevertheless, in the late afternoon, two heavy horses appeared, one light, and one dark, digging deep in the snow, pulling a sleigh and precious cargo wrapped in blankets and an old quilt.

As evening set in, Rosalia went outside to her balcony. She gazed at the church spires that grew from the hills, the barren trees that scratched the sky and the snow that entombed the streets. Another time the vista would be magical, but not today.

Then, out of the silence, she heard muffled cheering and sleigh bells from far away. “Come listen,” she called to Ivan. Through the snowy haze a sleigh and a crowd appeared over the crest of the bridge. The couple dashed down to the street in time to see Sarah at the reins of a team of horses. “Whoa!” she cried. They watched in wonder as she guided the sleigh to a stop in front of the barbershop. The horses stood steaming and snorting in the cold air. “Rosalia!” she cried. “We’ve brought you a present!”

Events unfolded quickly in front of them. The movers jumped down from the sleigh and pulled the coverings from the piano. Rosalia gasped and the townspeople shifted their gaze from the sleigh to her. “Ivanku, look! Tse moye pianino! It’s my piano!”

Without hesitation, the movers headed inside to measure the doors and stairway. After a few moments of tension, Jim the boss conferred with Cleave, and the two men announced with resignation that there was no way the piano would ever fit up the stairs.

The crowd was suddenly hushed until Catherine called out, “If the piano can’t go up the stairs, how about over the balcony instead?” Jim cast a skeptical glance at Catherine, but before he could say any more, the town sprang into action. Marge suggested removing the railing. The Andersons came up with the idea of tying a rope and pulley to the chimney. Cleave went for a block and tackle; a carpenter went for his tools; ladders appeared out of nowhere.

Sarah unhitched the team from the sleigh; the railing was removed; rigging was fixed to the chimney; ropes were secured to the piano and then lashed to the horses’ draw bar.

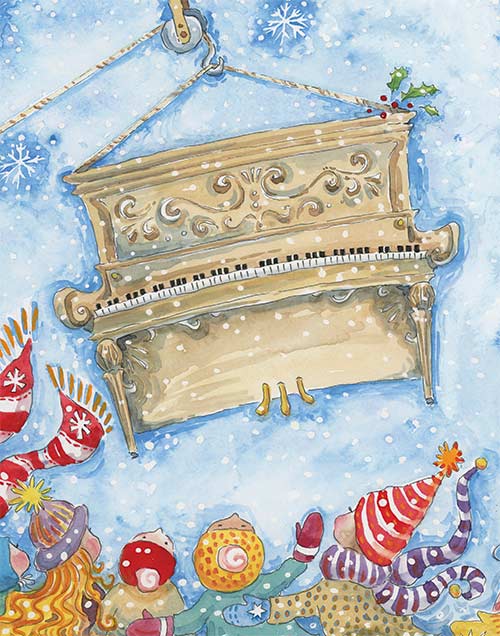

A quiet word from Sarah and the horses moved ahead; the team leaned into their harness; ropes tightened and pulleys yanked; the chimney held firm and in one graceful motion, the piano slowly climbed into the night. All eyes followed as it inched higher and higher. But all of a sudden everything came to a halt. Heads turned to see what the problem was, as the piano swayed like a pendulum in the sky, slowly coming to rest amid the gently falling snowflakes.

Then all by itself, the piano began to play.

To some townspeople it was a familiar tune. To others it was a brand new one. Ivan thought it was Bach. Some of the children thought it was the angels playing. Rosalia looked out at the townspeople who surrounded her, wearing her scarves, mittens and even the socks that she had knit. Perhaps, she said, the piano was offering a song of thanks, of love, and of peace. And maybe, as the children had said, a gift from the angels.

Story by:

Conrad Beaubien

Illustration by:

Katie Flindall