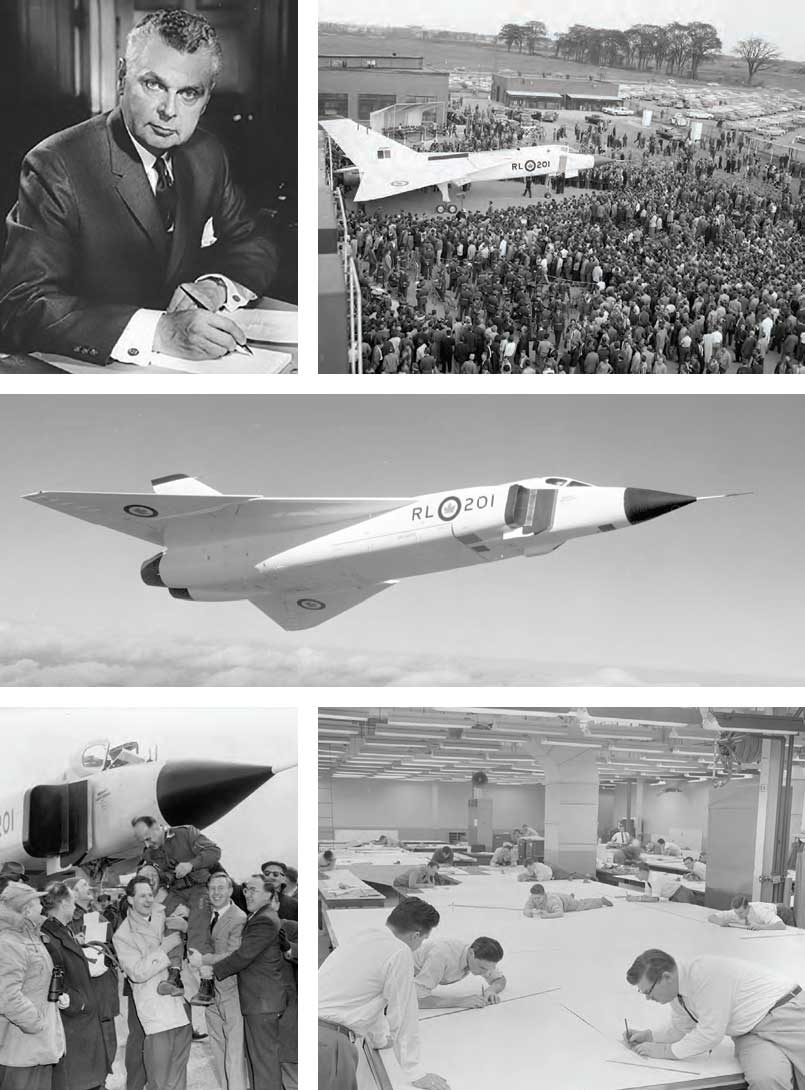

left to right and top to bottom: then Prime Minister John Diefenbaker; opening ceremony with a crowd milling around the Avro CF-105 Arrow RL201; welcoming Zurakowski after testing the Avro CF-105 Arrow RL201; transferring design instructions onto a master glass cloth for the reproduction of parts;

The Avro Arrow was a beautiful machine. It still would be, if there were any left. Orland French recalls the romance and mystique of the Canadian supersonic superstar that never was.

I was 13 when the first Avro Arrow was rolled out for public viewing in 1957. Sharp, clean lines. A magnificent delta-wing design. A dazzling white coat of paint. A futuristic twin-engine supersonic interceptor.

It was Canadian. It was acknowledged as the best of its kind in the world. Man, it made us swell with patriotic pride. I soon had a gleaming plastic model of an Arrow on my homework desk.

That was probably 40 years before I had my personal Arrow moment. I had travelled to Barry’s Bay to meet an author about the creation of a history book on the Polish community in the area. Her surname was Zurakowski, but I made no connection until she asked me if I knew her husband. “No, I don’t think so,” I said. “Yes, I think you do. Come with me.” She led me to another room where there was a balding, lean man I didn’t recognize immediately, except there was a huge portrait of an Arrow in flight on the wall behind him.

I realized with a shock I was in the presence of Janusz Zurakowski, the famous chief test pilot of the Avro Arrow. After the Arrow project was suddenly cancelled in 1959, he retired from flying and he and his wife Anna moved to Kamaniskeg Lake near Barry’s Bay in eastern Ontario, where they built and operated Kartuzy Lodge. Janusz told me he had picked out the site while he was on an Arrow test flight over the area. Janusz and Anna have both passed away.

If you are under the age of 50, you may not have a clue what I’m talking about. The CF-105 Avro Arrow was a state-of-the-art twin-engine all-weather interceptor fighter-bomber, designed, built and test-flown in Canada during the height of the Cold War in the 1950s. It was the best of its kind in the world at the time. It really was. It cruised at 1,100 kilometres per hour and topped out at 2,400 kph with full afterburners.

It was designed to knock down Soviet bombers as they flew over Canada on their way to attack the United States, a task it may have been quite good at, if it had gotten the chance.

CANADIAN PRIDE POWERS A LEGEND

The history of the Arrow project has its roots in the 1930s, when the Avro Aircraft Company manufactured the Hawker Hurricane and the Lancaster bomber for the Royal Air Force. C. D. Howe, one of the brilliant industrialists in Mackenzie King’s cabinet, obtained the licensing rights to produce the Lancaster in Canada. By the end of the Second World War, more than 120,000 Canadians were working in the aviation industry, 25,000 of them women. But when the war ended, so did the work.

Howe and others determined that Canada could build one of the finest aviation industries in the world. National pride was at a peak. We had established a reputation as a strong, reliable ally. We had fought our way up through Italy and up the beaches at Normandy, we had swept the Germans out of Holland and we had the fourth largest navy fleet in the world.

The Royal Canadian Air Force, which had barely existed at the beginning of the Second World War, had made a name for itself: approximately 10,000 Canadians would lose their lives in training accidents, in the skies over Europe or in prisoners of war camps. After the war, the RCAF was reduced in size to a peacetime role. But the Cold War between East and West was beginning to heat up. Although Canada did not enter any aircraft in the Korean War, Canadian fighter pilots flew F-86 Sabres on exchange duty missions with the US Air Force, shooting down a couple of the much-vaunted Soviet-built MiGs.

During the 1950s, the Soviet bomber threat grew. And if there was going to be a nuclear war between the US and the Soviet Union, the direct approach to America was going to be right over Canada. During those years, the RCAF had numerous aircraft that were suitable for low-level combat; but we had nothing capable of intercepting a bomber at high altitudes. To protect our turf, and the Americans to the south, Canada decided to build a high-flying supersonic interceptor to meet and knock down invading Soviet bombers. And so the Avro Arrow was born.

When we built the Arrow, early testing suggested it was going to be the best and fastest jet fighter in the world. Why then did it never really get off the ground? The trouble was that the Arrows were terribly expensive to design and build. Completion of the project and production of the aircraft was estimated to carry a price tag around $2 billion (an over-the-moon figure in the 1950s). In addition, the dawn of the space program and the possibility of threats from satellites and intercontinental missiles threatened the Arrow’s very usefulness.

Early on, some military officials were questioning the program.

When we built the Arrow, early testing suggested it was going to be the best and fastest jet fighter in the world. Why then, did it never really get off the ground?

DIEFENBAKER WIELDS THE AXE

Play a word-association game with older Canadians: Say “Avro Arrow.” If the person is over 60 years old, they are likely to reply, “John Diefenbaker.”

Prime Minister John Diefenbaker stopped the project abruptly in 1959. The government made the decision, but he was the designated villain for two reasons: killing the project and then, especially, ordering all the completed planes (five plus a nearly finished sixth) to be chopped up and destroyed, along with all plans and blueprints so that the plane could never fly again. Only one forward section of one aircraft, including the cockpit, was saved for display in a museum.

Politically, Dief got a raw deal. The Arrow project had been approved and initiated six years earlier under the Liberal government of Louis St. Laurent. From the beginning it was recognized as an ambitious undertaking. As it proceeded and costs began to roll up out of control, there was considerable nail- biting in the Liberal cabinet. By 1957, the Liberals were quietly conceding the project would likely be cancelled, but not right away. It was an election year, and the Liberals did not want the loss of 14,000 jobs in Toronto staining their record. They decided they would cancel the project after the election.

To their surprise, the Conservatives won a minority government on June 10. Suddenly Diefenbaker was holding the Arrow hot potato. But, like the Liberals, he was not likely to lay off thousands of workers when he held only a minority in the House. However, in the election of March 31, 1958, Diefenbaker won a whopping majority, and he could do whatever he wanted in Parliament. The Arrow was doomed.

In August 1958, Canada’s Chiefs of Staff concluded the Arrow was becoming a liability. Diefenbaker issued a writing-on-the-wall press release on Sept. 23, 1958: “…as the age of missiles appears certain to lead to a major reduction in the need for fighter aircraft, Canada cannot expect to support a large industry developing and producing aircraft solely for diminishing Canada defence requirements.”

The CF-105 Avro Arrow was the best of its kind in the world at the time. It cruised at 1,100 kilometres per hour and topped out at 2,400 kph with full afterburners.

THE SPACE AGE ARRIVES

Diefenbaker’s warning came almost a year after the first Arrow was rolled out into bright sunshine on October 4, 1957 to the admiring applause of thousands of workers and supporters. The irony of the day was that, far overhead, a 180-pound basket-ball size satellite, Russia’s Sputnik I, was spinning around the earth every 90 minutes. It had been launched that very morning. Although no one was ready to admit it, the age of interceptor aircraft was dead. The Arrow might as well have been called the Dodo. I can clearly remember that day. Not for the Arrow roll-out, but for Sputnik. I came down to breakfast in our sun-splashed kitchen, and my Dad was listening anxiously and sombrely to a radio news broadcast about the launching of the first Russian satellite. Although I was only 13, I had been indoctrinated with the propaganda of the day. I was well aware that the Russians were evil and this was not good. “Beep, beep, beep,” the satellite taunted, as it soared invisibly overhead.

Yet the Avro crew continued to build working Arrows: models RL-201 through RL-205. Chief test pilot Janusz Zurakowsky became the face, the heart and the soul of the mystical aircraft. The home base for the Arrows was the Avro plant in Malton, and only once did an Arrow rest its wheels on a tarmac away from home. It was on a test flight when an accident by another aircraft closed the Malton runway. The Arrow had to stay overnight at CFB Trenton.

As a nation we were so proud of our national accomplishment in a world of evolving aeronautical technology. And then, our optimism collapsed. On February 20, 1959, Diefenbaker ordered the immediate cessation of the Arrow program. Avro fired 14,000 workers right away. That was the first shoe to drop. The second, shortly after, was the order to destroy every aircraft and all blueprints and plans. The planes were cut up by acetylene torches on the spot.

THE ARROW MYSTIQUE

The Arrow mystique has a tremendous number of followers. More than 60 years after its brief lifespan, the Arrow continues to inspire books and magazine articles and films in North America and Europe. In June, 2020, the BBC published a lengthy article titled “The record-breaking jet which still haunts a country.” The article featured a dazzling photo of an Arrow in flight (even today it still looks futuristic). In 1997 the CBC produced an acclaimed four-part mini-series starring Dan Aykroyd. With some amendments, the series has been rebroadcast a number of times and inspired a Heritage Moment.

As for books, you could fill a library. And some people have. One of them was Peter Zuuring, who spent thousands of hours researching a series of books on the Arrow. He wrote in The Arrow Scrapbook, “It never ceases to amaze me that a project of this magnitude, started in 1953 and worked on so diligently by thousands of people for six years, could be so utterly destroyed by a handful of determined officials in a matter of days.”

As soon as the project was killed, the mystique of the Arrow was born. Could one of the aircraft have escaped destruction?

Writer June Callwood speculated that one did. She had already written about the Arrow and its Orenda engines. In a reflective article in Maclean’s Magazine in 1997, nearly 40 years later, she wrote of being startled out of bed on the morning after the project was cancelled: “Our house is in Toronto’s west end but distant enough from the airport that we rarely hear planes. The next morning, I was wakened before dawn by the loudest airplane engine sound I had ever heard. Its shattering roar filled the sky for a long moment and then suddenly was gone. ‘The Arrow!’ I thought in amazement. ‘Nothing else could make such a racket. Someone has flown an Arrow to safety.”’

“Maybe somewhere,” she mused, “perhaps packed in straw in a barn, one poignant Arrow remains.”

Derek Baldwin, a Belleville writer and reporter, has written dozens of Arrow-related stories, which have appeared all over North America. He is always astounded by the attention the topic receives. When he wrote a story last September about the discovery of an Arrow test model in Lake Ontario, the internet recorded a huge number of hits. This was sixty years after the Arrow project was killed.

He says, “The enduring legacy and myth following the cancellation of the Avro Arrow on that Black Friday is remarkable given the relative short memory usually demonstrated by the public regarding major national scandals. Decades on, we still seem to be unwilling to forget the day a so-called symbol of hope and a brighter tomorrow was taken from us. Canada’s self-imposed demise of the Arrow is a real-life fable of classic, unrequited love, forever destined to lie beyond our grasp. Purely and simply, the Arrow is a tale that invokes powerful human emotions of loss even to this day.”

And it’s not just we Canadians; the Arrow continues to attract international attention. In the BBC article published last June, Mark Piesing wrote, “The project was genuinely groundbreaking. Avro’s engineers had been allowed to build a record-breaker without compromise. But Canadians would soon discover that the supersonic age had made aviation projects so expensive that only a handful of countries could carry them out – and Canada, unfortunately, wasn’t one of them.”

SIXTY YEARS LATER, THE LEGACY THRIVES

In recent years the mystique has been kept alive by search and discovery missions looking for pieces of Arrow models that were test-fired over Lake Ontario. One-eighth scale, the models were boosted by rockets into free flight over Lake Ontario. The models – nine altogether – had been fired from a military property at Point Petre on the southwest corner of Prince Edward County. A project named Raise the Arrow! was organized and sponsored by Osisko Mining of Toronto. Osisko’s president and CEO John Burzynski lives in Prince Edward County not far from the underwater graves of the Arrow models. He says he caught the Arrow bug when he read about the discovery of the Franklin expedition ships which had been lost in the Arctic in 1845. Archaeologists found the ships nearly perfectly preserved in the cold water.

He began thinking about the Arrow models and wondering what condition they would be in – if they could be found. He determined to go looking. “We initiated this program with the idea of bringing back a piece of lost Canadian history to the Canadian public,” he says. “This project is a proud reminder of what we as Canadians have done, what we Canadians do, and what we Canadians can do.”

Raise the Arrow! recovered two of the models. Unfortunately, high-speed collisions with the water (at about 800 kph) had twisted and mangled the models, although the distinctive delta wing was still identifiable. They were also covered with mussels. Recognizing that the rest will probably be in the same condition, John Burzynski is uncertain whether the search will be renewed.

Was that dark day when the Arrow died the end of our national aeronautical pride? Not at all. Many Canadian engineers who were employed at Avro were snapped up within days for the American space development program. They helped put men on the moon, and Canada’s contribution to space exploration continues. There is Canadian physical content and brain power invested in the current NASA Perseverance rover exploration of Mars. In the next two years, we will place a Canadian aboard the four-person Artemis II mission to the moon. We didn’t waste our time on the Arrow. We were just getting started.

Story by:

Orland French

Illustration by:

Carl Wiens