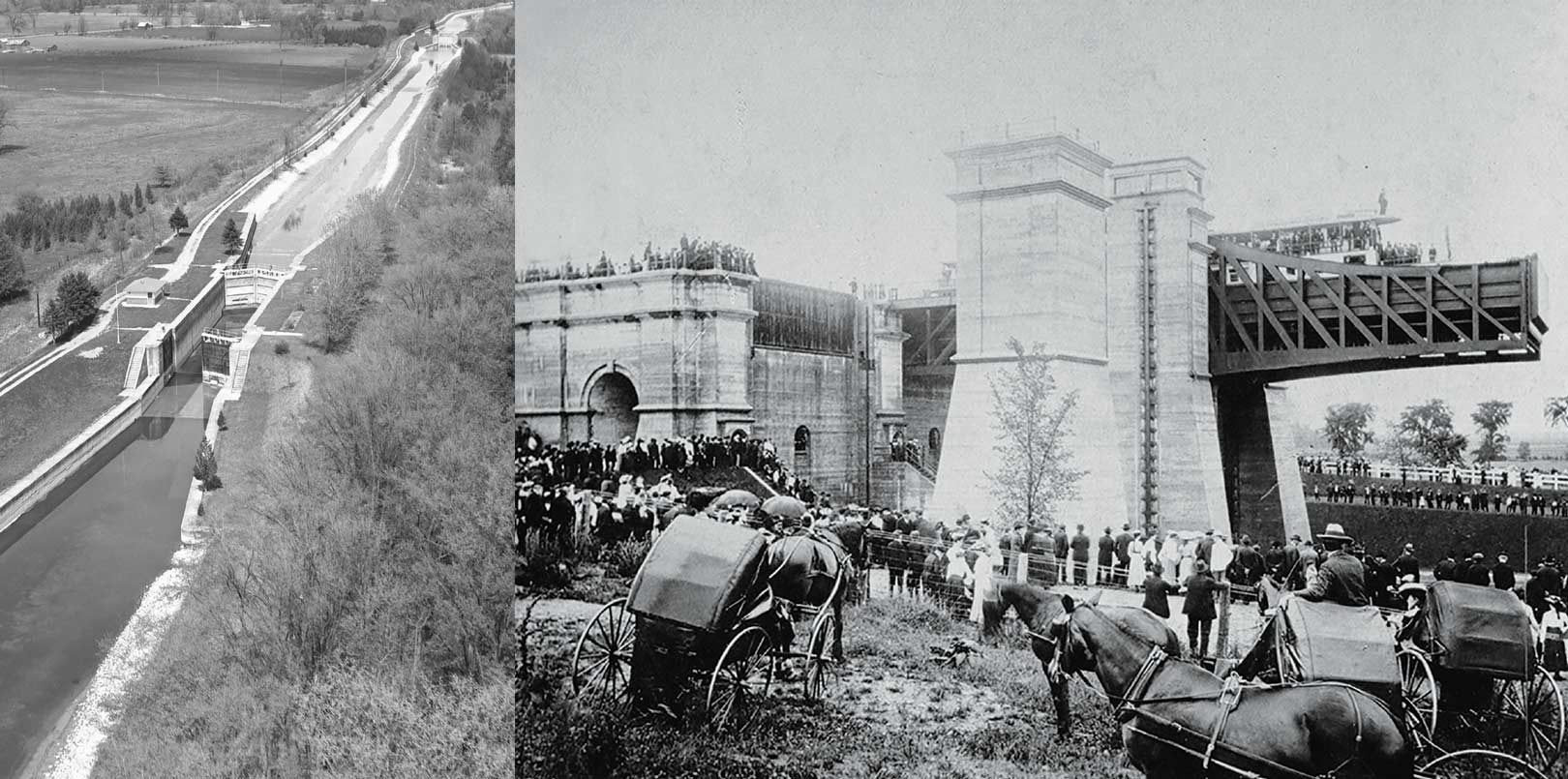

Top: Lock No. 40 (Thorah); Peterborough Lift Lock opening day, July 9, 1904; Bottom left to right: Dam and paper mill above Lock No. 3 (Glen Miller); constructing Peterborough Lift Lock, 1902; Flight Locks 16-17 (Healey Falls)

When the final section of the Trent-Severn Waterway was slated for construction, engineers and politicians were faced with two options: build the canal from Peterborough down to Trenton or through Rice Lake down to Port Hope.

Picture This: between Campbellcroft and Perrytown, somewhere in the rolling upper reaches of Hope Township (the old name for the rural part of Port Hope), a lift lock looms like a fortress over the countryside. It allows boat traffic to navigate a shortcut through the Oak Ridges Moraine from Rice Lake down to Lake Ontario. Only a mile or so downstream, a second lift lock takes boaters over another significant drop in elevation. Both are engineering marvels, the star components in the network of canals and locks that comprise the Trent-Severn Waterway. Unlike a conventional lock, in which sluices are opened or closed to adjust the water level, a lift lock could be likened to two giant boat-carrying bathtubs, one at the lower level and one at the upper. Using the principles of gravity and counterweight, it’s the “bathtubs” that rise and fall, not the water level.

There are only a handful of lift locks in the world, and as you probably know, two of them are on the Trent Canal. However, they are not in Hope Township: one is at Kirkfield and a second more famous lock stands at Peterborough. The latter, in particular – accommodating a 20-metre descent – is a prized local landmark that attracts thousands of visitors, who watch its operation in awe each summer.

It was argued that the Port Hope route was cheaper, despite the necessity of digging through the moraine.

And you probably also know that the Trent Canal goes nowhere near Hope Township. But there was a time when the idea of connecting Rice Lake to Port Hope with a canal, complete with two lift locks, was a real possibility and much touted by town fathers eager to enhance local fortunes. Farther east, however, businessmen and other boosters in Trenton made a similar plea that their town was the logical choice for the eastern terminus of the Trent Canal. The debate quickly escalated into a war of words between the two towns, and wasn’t resolved until much later. And as we all know, Trenton won.

Stretching from the southeast corner of Georgian Bay, through Lake Simcoe to the northwest corner of the Bay of Quinte, the Trent Canal (now officially named the Trent-Severn Waterway) follows a diagonal 386-kilometre course through a seemingly random network of inland rivers and lakes. To avoid rapids and waterfalls, each link is connected by canals and dozens of locks. The canal shortens the water journey by 650 kilometres, bypassing most of Lake Huron, all of Lake Erie and the western half of Lake Ontario.

At the time of its conception in the 1830s, the intent of the proposed canal was not so much to save navigation time, but to provide an all-Canadian military route between the upper Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River, safe from American interference during a period when US expansionism was a real fear.

But the Trent Canal proved to be a tough sell, partly because the newly completed Rideau had stunned politicians with its staggering price tag of $4 million. Nonetheless the first lock, connecting Sturgeon and Pigeon Lakes at Bobcaygeon, was opened in 1833 and work began on an additional four more. By then, the canal’s purpose had shifted from military to commercial uses.

PORT HOPE PUTS IN ITS OAR

Numerous private/public partnerships were forged to promote construction on the canal. One of these proposals came from businessmen and politicians in Port Hope, who organized the Port Hope Canal Co. to assess the feasibility of building a waterway from Rice Lake through the Ganaraska valley to Lake Ontario. In 1833, an engineer named Robert Maigny was hired to survey the most logical route.

You don’t have to be an engineer to know that Maigny faced a major barrier right off the bat. “A very formidable difficulty presents itself within a few yards of Rice Lake,” he reported, “in the form of a ridge of land stretching in an east and west direction [all the way to] the state of Ohio.” The reference to Ohio is wholly inaccurate, but Maigny is of course talking about the Oak Ridges Moraine. Wherever he drew his map, his canal would require lots of locks in order to shuttle boats from Rice Lake to the moraine’s summit and then down the other side toward Lake Ontario.

Maigny’s report is still kept in the archives at Trent University, but the map documenting his proposed route is missing. Even so, his written description contains enough landmarks – “Howe’s Creek,” “Mr. Riddle’s land,” “Lot 9 Concession 6,” “Boen & Coy’s millpond” – that if you know historical Hope Town – ship, you can trace the way with some accuracy. From Bewdley at the southwest corner of Rice Lake, Maigny proposed a ditch be dug due west, which would then take a turn along a canalized creek to climb the moraine. At the summit, locks would connect with a brook on the other side for the long downhill ride to the main branch of the Ganaraska River, which would be dredged all the way through downtown Port Hope to Lake Ontario.

Maigny’s route was significantly shorter than the more circuitous path farther east to Trenton. It was also argued that the Port Hope route was cheaper, despite the necessity of digging through the moraine. However, the report, like many before and since, was shelved and nothing was done for the next seven decades. From then on – and for almost a century – there would be any number of excuses and obstacles thwarting the idea of an open route between lakes Ontario and Huron.

LANDLOCKED

By the 1880s, there was some progress on the Trent. Now under the jurisdiction of the federal government, the canal connected most of the inland Kawartha lakes. But with neither an eastern nor a western outlet to the Great Lakes, the Trent was, in effect, landlocked with limited commercial potential. In the 1896 federal election, it found a new champion in none other than Liberal leader Wilfrid Laurier, who saw the completion of the canal as a great incentive for local industry. A savvy politician, he also knew the canal could sway votes toward the Liberals in an area that was traditionally Tory. He won the election handily and all of a sudden the Trent Canal was an urgent priority.

The great irony was that by then, the canal was largely obsolete, whether or not it was a through route. Its military function was a distant memory, but even its commercial viability was questionable. Many of the locks would soon be too narrow to accommodate ever-larger cargo ships; but most of all, the canal was hopelessly cumbersome compared to the new network of streamlined railways that had boomed since the 1850s and cut shipping times from days to hours.

Determined to show voters their tax dollars at work, Laurier persevered, but the canal itself was actually secondary in his plans. Far more important than boat traffic was the great opportunity to slake the new public thirst for hydro power. The hydroelectricity generated by the dams along the canal system proved to be even more of a political plum than navigation. Suddenly, the engineers had a new reason to take a second look at Maigny’s dusty old report.

BACK TO PORT HOPE

In 1900, canal superintendent Richard Rogers reexamined Maigny’s route between Port Hope and Rice Lake and reduced the number of locks to 13, including two lift locks. Even so, the hump over the Oak Ridges Moraine would still require a lock every quarter mile or so, and it didn’t help that much of the original course down the Ganaraska valley had since been occupied by the town’s northbound railway.

Ultimately, the awkward topography is not what doomed the Port Hope bid. The problem, Rogers reported, was simple and insurmountable: the open water on Lake Ontario between Port Hope and Kingston was rough enough to scuttle any small canal barge. All cargo would have to be transferred onto larger lake-going vessels in Port Hope harbour, Rogers reported, and then loaded again onto ocean-bound ships at Montreal. This extra laborious step was the deal-breaker. “The usefulness of the whole canal [via Port Hope] as a commercial factor for a through route would be done away with,” he wrote, noting that the route between Trenton and the St. Lawrence River didn’t have this problem. It was perfectly sheltered by the Bay of Quinte all the way to the head of the St. Lawrence.

Likewise, the Trenton route presented far more opportunities for hydroelectric dams.

And that’s why, to this day, there are no lift locks along the Ganaraska, no summer crowds gathering with dripping ice cream cones watching boaters waiting patiently in their sluices as the lockmaster opens and closes the massive chutes that control the water levels along the Trent Canal.

Story by:

Tom Cruickshank