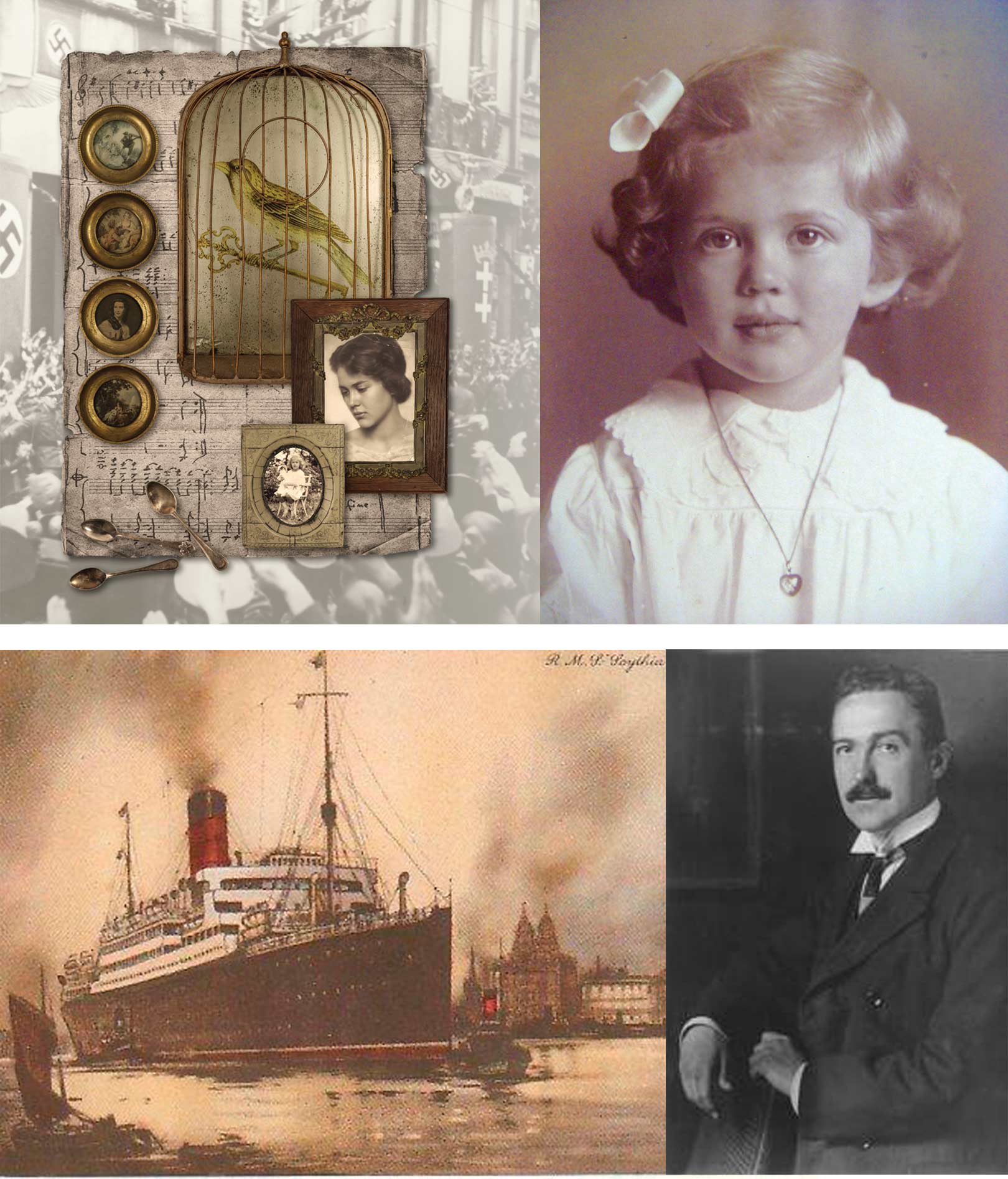

left to right: RMS Scythia carried Vera Teleki’s family to Canada; Professor Hans Przibram, Vera’s father; Vera as a child

Saromberke Castle: Charles Teleki's “country home in Transylvania” was a lavish 90-room castle in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains.

When Vera Teleki died in Cramahe at the age of 101, few of her neighbours knew that they had been enjoying their morning coffee with a European aristocrat whose life was defined by romance and tragedy, wealth and poverty, drama and determination.

There was never anything ordinary about Vera Teleki. She lived well into her 101st year, more than half of it spent in the back hollows of Cramahe Township. When her husband died, she chose to live out the last 34 years of her life alone, with poetry and nature in their rustic farmhouse. You might say she earned it. Her lifetime spanned some of history’s most cataclysmic events – two world wars, the Great Depression, the Holocaust, the mass exodus of displaced Europeans to the New World – and hardly anyone knew that she’d experienced it all first-hand.

Old-timers in Cramahe remember Vera and Charles Teleki as the mysterious couple who moved into the old Dawson house with three of their children in 1953. The remote farmhouse had no indoor plumbing or electricity and there was a gaping hole in the roof. The Telekis knew little about farming. They spoke foreign languages and sent their youngest children to Castleton Public School to learn English. They somehow made it work. Vera and Charles often “shopped” at demolition sites for bits of furniture, which she’d adapt and install as bookshelves and painted cabinets in their new home. Charles travelled door to door selling his eggs, looking aristocratic and out of place, always in a suit and tie with his black hair swept back and curled up at his collar in the European manner. To their new friends, they were just “Vera and Charles.”

Over the next decades they socialized with the county’s more illustrious residents, including the Masseys and Blaffers, drawn in mainly by Charles’s passion for bridge and the couple’s knowledge of world events. A privileged few, all women more than a generation younger, remember the weekly gatherings that Vera hosted in her parlour, everyone captivated by her stories and the old-world paintings and etchings that seemed to cover every wall. It wasn’t until she died, and her son placed an obituary in The Globe and Mail, that most of us learned she had also been someone else – the Countess Vera Phyllis Teleki (née Przibram), born June 28, 1910, in Vienna, Austria, daughter of Professor Hans and Countess Anna Wanda Przibram (née Komorovska).

And therein lies a great story.

The pictures on the walls were of the couple’s ancestors, who included a former prime minister of Hungary and various counts and countesses, living in grand castles. But war and communism forced Vera Teleki and her family to leave behind the world depicted on those walls – a world of almost unimaginable wealth and privilege.

In the early 1900s, Vienna was the centre of European culture and accomplishment, but it was also squarely in the crosshairs of both world wars. Vera would tell her son how her fourth birthday party was ruined by news of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria. His death that day led to the outbreak of the First World War and the downfall of the Habsburg Empire.

As a child in Vienna, she occasionally entertained her father’s academic colleagues at afternoon teas. Guests included Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud, and young Vera captivated them by talking in rhymes, a natural talent that she discovered early and later developed into a treasure trove of her own carefully composed poems and haiku verses. “Freud,” she once reported, “had a smelly beard.”

PARADISE LOST

Her life and that world were torn apart forever when the Nazis annexed Austria in 1938 in the notorious action known as the Anschluss.

Her son, Geza Teleki, an international environmental consultant, is emotional when he talks about the meaning of his mother’s life. The family’s survival, he says, “is all due to Mother. She’s the one, with amazing will and strength, who got her children out of harm’s way”.

For the rest of us, Vera Teleki’s story is about someone who found quiet refuge in Northumberland County, mastering her family’s survival against great odds, helping to raise eight accomplished children. But for Vera’s optimism and indomitable will, things would have turned out so much differently for them all.

In her long life, it was always about the children, and when six of them from three continents spoke at her memorial, it was clear they cherished her with a fierce, grateful and never-ending love.

The Anschluss was one of the first steps in Adolf Hitler’s creation of an empire of German-speaking lands that he felt had been taken away after the First World War, and he unleashed the Gestapo to sow terror among his new Austrian subjects. Adolf Eichmann, like Hitler a native of Austria, used that country to develop his model for solving “the Jewish problem.” This involved evicting the Jews or sending them to death camps and keeping as much of their wealth as possible.

Vera was living in Vienna with her first husband, a wealthy textile merchant named Paul Dukes whom she’d married when she was 19. The Gestapo knew that Dukes had many Jewish friends in high places in Vienna and they wanted the names, so they went after him.

As a child in Vienna, Vera occasionally entertained her father’s academic colleagues at afternoon teas. Guests included Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud, and she captivated them by talking in rhymes. “Freud,” she once reported, “had a smelly beard.”

“As the story goes,” says Geza, “the interrogation became increasingly intense, and after about the fifth time, he came home and didn’t want to show my mother what they’d done to him – how they’d mutilated his body. He told her that he couldn’t bear it another time. It was too much, he was going to crack, and they’d come after her and the children.” They made a fateful decision together.

“It’s the details that make this so …” Geza says haltingly. “They lived on one of the main streets of Vienna and he had built for my mother a veranda on the third floor, so she could sit out and view the passing scene. That’s the veranda that he jumped from.”

After her husband’s defiant suicide, the Gestapo interrogated Vera. On one pivotal occasion, when the threats became too much, she said to her interrogators, “Stop it. Just do it.” Either the Nazis were shaken by her courage or they needed new orders, so they allowed her to go home. A sympathetic German officer warned her that she had to get out, or she and her family would be killed.

For those lucky enough to escape, the price was heavy: special taxes of all sorts, for visas, passports, health certificates. Vera traded her jewelry for the necessary documents and fled to Budapest with three young children under 10. She left everything else behind for the Nazis.

The rest of her family was not so lucky. Her father, who was a distinguished professor at the University of Vienna, tried to flee too, but the Nazis caught up to him in Holland. Hans Przibram was the founder of experimental biology, and his laboratory, or “Vivarium,” was known to every natural scientist who came to Vienna. But he was Jewish, and after the Anschluss, Nazi students distributed blacklists of Jewish and socialist professors, demanding restrictions and dismissals. The university banned his work and his lab was destroyed. The Germans came up with a scheme to flush Jewish intellectuals out by offering to house them in a “utopian city” called Theresienstadt (Terezin) in Czechoslovakia. Professor Przibram accepted the invitation and was gassed with all the others in 1945. Vera’s older sister Margaret perished in another camp.

The loss of her family and husband in the Holocaust haunted Vera Teleki until her dying day.

A NEW START

She arrived in Hungary in 1940 not knowing a soul and supported herself and her children by working as a medical illustrator, drawing images of organs for hospital textbooks. As luck would have it, she was introduced to Charles Teleki, from Transylvania with three children of his own to raise. He fell head over heels for the beautiful, elegant Vera. She was initially unimpressed, but that changed when she got to know him better and he invited her to visit him at his country home in Transylvania. Charles Teleki was actually a Hungarian aristocrat. His “country home in Transylvania” turned out to be a lavish 90-room castle, with a small army of servants on an estate that covered 30,000 hectares in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains.

Vera once explained to Geza: “He was alive and fun, at a time when most everyone was not.” She’d never seen anything like Saromberke Castle, which had been the Teleki ancestral home since 1485. “My mother had wonderful stories. She told us of the opulence there,” Geza says. “She’d go from room to room and there’d be Louis XIV furniture stacked to the ceiling in one and damask linens in another, in such quantities that they were often only used once. They were even used to clean their shoes.” European aristocrats gathered regularly at Count Teleki’s invitation for polo matches and hunts.

Charles and Vera married in 1944 and merged their families. But that same year, German forces occupied the country and it became a battleground. The key to their survival was the Teleki name, which all through Hungry was synonymous with honesty and patriotism.

Says Geza: “That saved my father’s life during one incident he recalled to me, when partisans arrived at their estate in southern Hungary, were about to take most of the livestock and set him up against a wall to execute him and asked what his name was. My father considered lying, not knowing what would happen, but decided to tell the truth. When they heard Teleki, they apologized profusely, returned all items and left him alone.”

The invading Russians, however, were another story. Vera managed to survive many run-ins with them. One day in 1945, a battalion of loutish soldiers arrived and gave them 20 minutes to leave. Vera stood her ground. She apparently just said “We’re staying.” Later that year, pregnant with Geza and with her husband in a labour camp, Vera was arrested on a train travelling to Saromberke, where she wanted their son to be born. Transylvania had been annexed to Romania in 1945 and she had no authorization to be there. She was thrown in prison in Bucharest for six weeks until an amazing thing happened. The former king of Romania, whom the Russians had forced to abdicate, intervened on her behalf because she was a Teleki. Geza was born soon after her return to southern Hungary.

“I would always ask how she managed it all,” Geza says. “And she’d just say, ‘There was no choice, Geza. It was either do it or die, and I had the will to live.’” It is a miracle Vera and Charles escaped before the Iron Curtain fell shut. The full story of her seven-hour walk through dark forests back to Austria carrying her two-year-old daughter lies in a three-foot-high stack of transcripts taken from reminiscences of her life that her children encouraged her to tape record. Her daughter once joked that the tapes were so dramatic they would make a great script for a Steven Spielberg movie.

A NEW WORLD

Her survival skills acute, Vera persuaded Charles, who was stubbornly convinced that communism wouldn’t last long, to leave first Hungary and then Austria. They had to leave behind the incredible wealth his family had accumulated over hundreds of years. All they could salvage were some pictures and one set of silver coffee spoons. In the spring of 1953, with seven of their eight children, they sailed for Canada on RMS Scythia. “I believe that she had just enough to pay for the ship crossing, the short stays in various cities, our 1948 Buick and the down payment for the farm,” Geza says. “In other words, we were virtually penniless in 1953 when we arrived in Cramahe.”

The Telekis were ill-suited for the hard life of farming the 36 acres of marginal land in what was then the backwoods of Ontario. Vera had never cooked. Charles had few skills other than his energy and charm. Most of his life he’d awakened to a valet inquiring about which outfit Count Teleki wished to wear that day. But the rundown place in Cramahe was all they could afford, and the countryside reminded Vera of southern Austria. When they arrived after an all-day drive from Toronto, Vera announced: “Well, I’m afraid this is it.”

Making a success of their new life depended on Vera’s determination, optimism and resourcefulness. The first winter, everyone slept together to keep warm. Come spring, their road turned into a quagmire. They’d have to leave for town before 6 a.m., before the frost melted, and couldn’t come home until after 6 p.m., when the ground was hard again. A friendly neighbour, curious about the exotic foreigners, educated them about farm life, saying the snakes under the porch had their uses, and to watch out for poison ivy.

The older brothers, who a decade later would become high level professionals, worked as tobacco pickers and bus dispatchers elsewhere in Ontario and sent what they could to help. Charles planted a vegetable garden that soon became the envy of the region. They also raised chickens – 30,000 of them at one point, along with 600 laying hens – so Charles would go to Cobourg and sell slightly cracked eggs at a discount door-to-door. “My father was very flamboyant, a raconteur, the life of the party,” Geza says. “He looked like a man from some faraway land, and people would gravitate to him.”

His salesmanship gave them their only piece of fine furniture – an upright Steinway piano. Geza was with him one day when a woman who was buying eggs invited them in for tea. Charles complimented her on her fine piano. “Well, do you play?” the woman asked. And he responded, “Oh yeah, sure, I play.” Charles played Liszt for her with such classical flourish that Geza remembers, “the lady couldn’t believe what she was seeing. As we were walking out she said, ‘You know, I don’t play very much. Would you like it?’”

The piano graced their farmhouse for 10 years until its massive weight caused the floor to list ominously, and it was moved to the woodshed. There it languished, but was played regularly until the great ice storm of 1971 when the roof collapsed and crushed it.

The Telekis had to leave behind the incredible wealth the family had accumulated over hundreds of years. All they could salvage were some pictures and one set of silver coffee spoons. In the spring of 1953, with seven of their eight children, they sailed for Canada on RMS Scythia.

Vera pulled the plug on the chicken business in 1962 when everything was repossessed – even the barn. “We still had a mortgage; we still had to pay bills,” Geza says. Vera and Charles took part-time lodgings in Toronto and did odd jobs. “My father tried everything, from being a bouncer in the red light district on Jarvis Street to selling those little Japanese cameras … I think he sold three.” Once again, it was going to be up to Vera. “At the age of 55, she had to reinvent herself,” her son says. She landed a job in the rare books library at the University of Toronto and stayed there for 10 years. “She transformed the way that rare books are displayed,” says Geza. “She designed and launched amazing exhibits, to the point where she became quite well known.”

After her mandatory retirement in 1975, the couple returned full-time to the farm, where Charles died in 1977. He’d always missed the life they’d had to leave behind, but said that his greatest joy was that he had his family around him and that they were safe. Vera devoted herself to running the farm, keeping the family connected, and writing poetry and stories, which she also illustrated and read to her grandchildren.

In her long life, it was always about the children, and when six of them spoke at her memorial, it was clear they cherished her with a fierce, grateful and never-ending love.

“The themes were always birds talking with plants, always something to do with the nature around here,” says her son. “She never had them published. She tried. I have one of the letters written in 1978 by a publisher saying that birds talking to plants is not appropriate for young children.” Geza still laughs about that today.

COFFEE WITH ARISTOCRACY

When Susan Johnston and her husband moved in around the corner in 1993, “I heard that this elderly Hungarian woman was living alone. You can imagine what I thought. Moving to the country, you expect to meet salt of the earth types. I had no idea I was going to meet anyone like Vera.” Even though Susan was 40 years younger, she became fast friends with the elegant, cultured, beautiful and feisty Vera, and the Tuesday morning coffee klatches began.

“We were the privileged few,” Susan said of the women who gathered to share Vera’s love of nature and hear her exotic stories. Although locals knew from the arriving mail that Count Charles Teleki had once lived there, “I don’t think people really understood what that meant,” she said. “They had no idea about Vera’s past and what she had gone through.” Hearing Vera tell about her childhood in Vienna and her escapes with her children, “you’d wonder sometimes if it was exaggerated. But when I heard the stories at the celebration of her life, I realized how understated she’d made them.”

“Tuesday mornings became sacrosanct,” Susan said. “We were sworn to two rules. First was: what’s said at coffee klatch stays at coffee klatch. The second was: no underpinnings required. She’d just host us in her pyjamas.”

Susan’s sister-in-law Irene was also part of the group. She’d been born in Austria and sometimes chatted with Vera in German. “We’d walk the streets of Vienna together as kindred spirits,” Irene said. “I don’t think I ever heard her say she was unhappy. She was always up, and curious about everything. You’d walk in and she’d say ‘Do you have a story for me? And then I’ll tell you one.’ That’s how it began.” Vera died in Florida in 2011 and her ashes were flown back to Cramahe and scattered on her favourite spots at Millcrest Lodge, her name for the farm.

All her children were at the celebration of her life as were the many friends she had drawn into her magnetic orbit over the years, like David Warburton. He’d been adopted by a man who had fallen in love with Vera when they were teenagers in Vienna, but their families disapproved. Long after the war, he managed to find her in Canada and their new families became friends, Vera becoming a mentor to David. “Nobody I have encountered in my heart and universe,” David wrote in his emotional eulogy, “could hold a candle to Vera Teleki.”

A simple, unmarked heart-shaped stone cairn now stands for Vera in her farmyard, next to the linden tree that had been planted to mark the 100th anniversary of Count Teleki’s birth. And so, after half a lifetime of being on the run from history, Vera and Charles were at peace together, their monuments lying side by side, forevermore, in their beloved hills of Northumberland.

Story by:

John Miller

Photography by:

Alana Lee