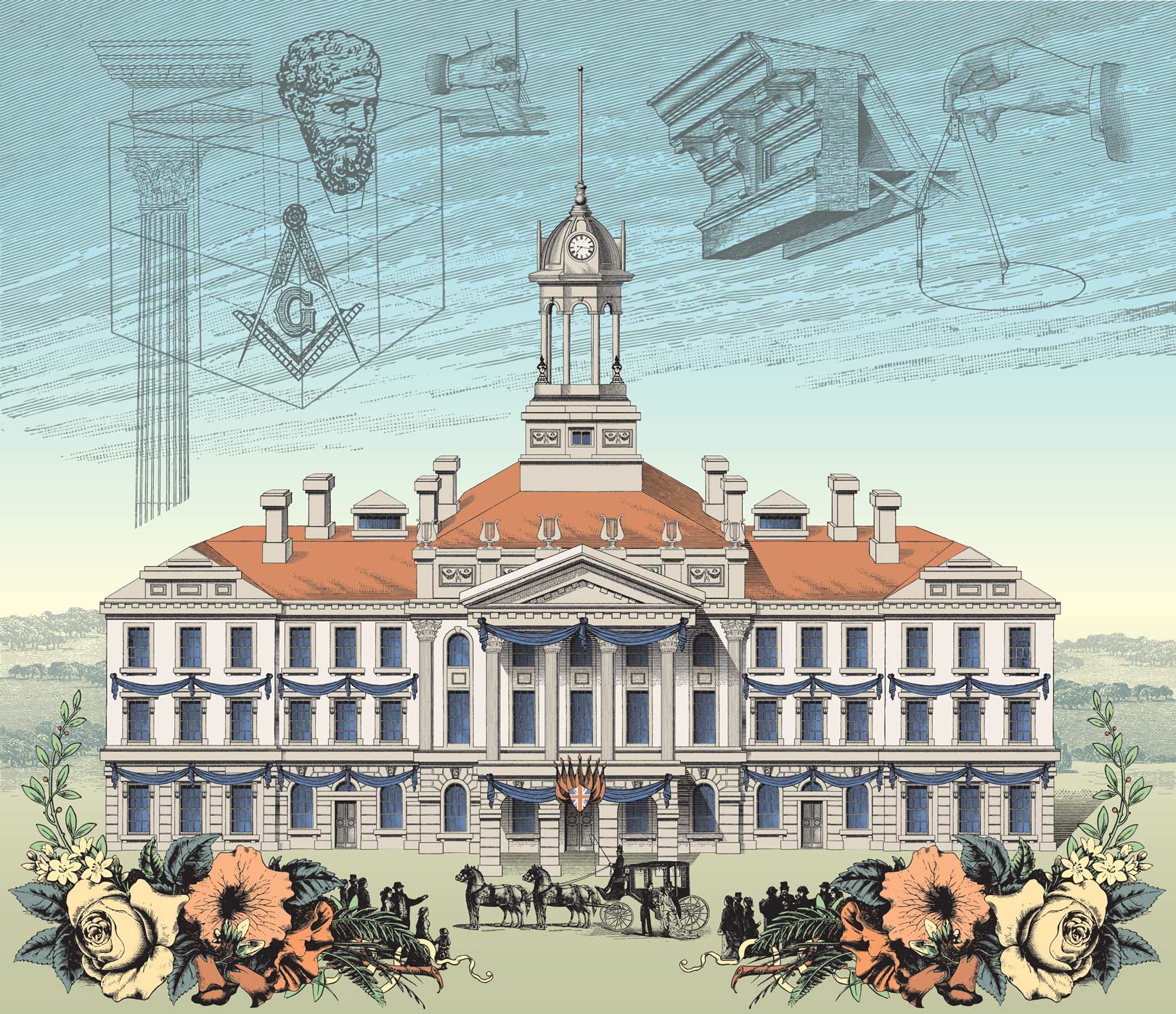

Left to right: Pythagoras looks down from his perch; a early rendering of Victoria Hall; John Taylor inspects a Corinthian capital during Victoria Hall’s restoration

Left to right: The trompe de l’oeil ceiling of the concert hall; visit of Duke and Duchess of Connaught, 1913; Architect Kivas Tully

The town fathers had gambled on Cobourg’s future, but whether their daring dreams of success were in the cards or not, Victoria Hall with all its stately grandeur has steadfastly stood as the town’s cornerstone for over a century and a half.

What is it about Victoria Hall? Cobourg’s town hall is unquestionably a handsome, historic structure – but so is Toronto’s St. Lawrence Hall, to which it is often compared. And Kingston’s city hall is an even more imposing neo-classical building from the same era. Yet neither of those historic halls can please the eye and lift the heart quite like Victoria Hall. So how did the building that has been Cobourg’s most prominent landmark for over 160 years come to be designed with such presence and harmony? In his documentary film, The Grand Gamble, John Taylor recalls the evening in 1970 when, as a young curator applying for a job at the Cobourg Art Gallery, he first “met” Victoria Hall. “She was a sombre, dark, brooding presence in the twilight, yet very fascinating. I had no idea that a building this grand and this stately existed in Ontario.” As he walked around the hall, Taylor wondered, as have many others, “why and how did she get there?” His fascination with Victoria Hall would lead him to become a key figure in the battle to preserve the building after it was threatened with demolition in 1971. And in The Grand Gamble, Taylor recounts how the ambitions of Cobourg’s town fathers in the 1850s led them to invest in a building they thought would help position Cobourg as a civic centre to rival Kingston and even Toronto.

It was a time of dynamic growth for this bustling town on the lake. The economy was booming and Great Lakes schooners filled the harbour and lined the wharves. The aspirations of the local politicians had been given a further boost in 1850 with the news that the Grand Trunk Railway linking Toronto with Montreal would go right through Cobourg. The town then decided to invest in a daring scheme: a railway link from Cobourg to Peterborough that would allow grain, lumber and other goods to be transported south to the waiting ships in Cobourg’s harbour. Track-laying for the railroad started early in 1853 and by May it had reached the shore of Rice Lake. Work then began on a three-mile wooden trestle bridge across the lake, which would be the world’s longest.

Confidence in Cobourg’s future was increasing on all fronts. In 1852 the town sponsored an architectural competition that solicited designs for a new town hall. The competition produced plans for a modest structure, in keeping with the budget of five thousand pounds; however after some consideration, Cobourg’s mayor and town council realized that they should set their sights higher, envisioning a grander undertaking that would produce a building “not just for present but for future purposes.” Toronto had recently opened the St. Lawrence Hall. Why shouldn’t Cobourg have a civic building that was similar – but even better? And so they approached Kivas Tully, giving the young architect the opportunity to outdo his rival, William Thomas, who had previously beaten him in bids for both the St. Lawrence Hall and St. Michael’s Cathedral. To date Tully’s most notable architectural commission had been the Trinity College buildings on King Street in Toronto, which he had designed in Elizabethan Gothic style.

Kivas Tully emigrated from Ireland in 1844 at age twenty-four. After his first wife died in 1847, he married Maria Strickland, the daughter of Lakefield pioneer Sam Strickland, and niece of writers Susannah Moodie and Catharine Parr Traill. His father-in- law asked him to create plans for Christ Church in Lakefield, and this led to a commission to redesign the chancel for St. Peter’s Anglican Church in Cobourg. These two ecclesiastical endeavours in turn facilitated his bid to become the architect for the new town hall.

FREEMASONRY

Kivas Tully was a Freemason, a member of a fraternal society that had its roots in the medieval guilds of stonemasons. The Masons had evolved over time into a worldwide organization with millions of members meeting in Masonic lodges, which were particularly ubiquitous in English-speaking Canada. It has been estimated that in the nineteenth century, one in every twenty-five adult men in North America was a Freemason.

The Freemasons revered the work of Andrea Palladio, a sixteenth-century Italian architect best known for creating beautiful villas near the towns of Padua and Vicenza. His work harkens back to the style of the ancient temple of Solomon. Palladio’s treatise, The Four Books on Architecture, which describes the Roman buildings that inspired him, was required reading for all apprentice Masons.

Freemasons like Inigo Jones and Christopher Wren brought Palladian architecture to England in the seventeenth century, and St. Paul’s Cathedral is thought to be Wren’s incarnation of Solomon’s temple. George Washington was also a Freemason and this is believed to have influenced the neoclassical style of the US Capitol Building. And when Kivas Tully designed Victoria Hall, he followed Palladian principles, using geometric proportions, elegant porticos and rounded windows.

As a Freemason, Tully was in good company: US Founding Fathers Benjamin Franklin, Samuel Adams, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton and John Hancock were all Masons, as were 11 out of the 37 Canadian Fathers of Confederation, including our first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald. The roster of famous Freemasons extends from Mozart and Haydn to Robbie Burns and Mark Twain to Clark Gable and Peter Sellers.

However its gallery of famous adherents has not prevented Freemasonry from being linked to countless conspiracy theories.

MYSTICISM, THE MAGIC FLUTE AND VICTORIA HALL

Secret rituals and esoteric beliefs that members of Freemasonry are forbidden to divulge to outsiders have led to accusations of everything from Satanic worship to plots of world domination. (For conspiracy-meister Dan Brown, author of The Da Vinci Code, Freemasonry provided irresistible fodder for his 2009 novel The Lost Symbol.) Though sinister theories about the Masons are questionable, there is no doubt that the mysticism of Masonic beliefs and practices has profound meaning for its members. In his opera, The Magic Flute, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s enthusiasm for Masonic mysticism can be found in the libretto and score. The young prince Tamino must undergo a series of trials that were part of Masonic ritual at the time. The opera opens with three portentous chords – three being a number of profound importance to Freemasonry. Three candles are lit before Masonic lodge altars and three knocks on the door occur before ceremonies; there are three Masonic degrees (Entered Apprentice, Fellowcraft and Master Mason); three principal officers, three stages of life – and the list goes on and on. The number three reappears in The Magic Flute with the three ladies of the Queen of the Night who present Tamino with the magic flute, and the three boys who guide him to the mysterious temple with three doors.

The number three was similarly employed by Kivas Tully in his design for Victoria Hall. The windows are arranged in threes in the two wings that flank the central portico. And three arched doorways mark the entrance to the building, echoing the three chords at the opening of Mozart’s opera. Victoria Hall reflects the geometric proportions of Palladio so prized by Freemasonry. The “G” at the centre of the Masonic compass-and-square emblem stands for Geometry, which Masons believe measures the harmony in the universe. Atop and above Victoria Hall’s handsome portico stand seven ancient lyres, symbolizing that harmony. The portico is supported by fluted pillars with beautifully carved Corinthian capitals – Corinthian being the classical order that symbolizes beauty in the Masonic canon.

Kivas Tully knew that the hall would house a Masonic lodge, and that the cornerstone would be laid by Sir Allan MacNab, the Masonic Grand Master – and also Premier – of the United Province of Canada. Sir Allan had gained his knighthood after leading a militia that had rousted William Lyon Mackenzie’s rebels during the 1837 Upper Canada uprising. With profits from land speculation, he had built a 40-room Italianate mansion for himself in Hamilton, known as Dundurn Castle. He left home by train on the morning of December 30, 1856 and arrived in Cobourg in time for a grand procession along King Street and a welcoming speech by Mayor D’Arcy Boulton. (As a scion of an elite Toronto family, Boulton was well acquainted with MacNab.) Sir Allan then tied his Masonic apron around his ample middle for the cornerstone-laying ceremony. Masonic aprons were meant to evoke the aprons worn by ancient stonemasons, though MacNab’s apron was undoubtedly tasselled and embroidered with symbols indicating his high Masonic status.

One puzzle that has eluded historians is the identity of the “fine bearded face” on the keystone above the main doorway. It surely must have some symbolic or allegorical meaning, yet there is no record of who it is meant to be.

COMMUNITY CORNERSTONE

In the cavity of the building’s lower cornerstone, a bottle filled with coins, copies of the two local newspapers and other artifacts were placed and sealed with cement. The town band then played “God Save The Queen” as the upper stone was lowered into position and the Masonic ritual began. Sir Allan received the plans from Kivas Tully and anointed the cornerstone with corn, wine, and oil – Masonic symbols of prosperity, health and peace – and offered the dedication: “Bless this work here begun that it may arise in order, harmony and beauty.”

By early 1857 the outline of the walls was clearly visible, constructed of white brick by the local firm of William and David Burnet. Barges of buff Cleveland sandstone, with which the building would be faced on three sides, began arriving in Cobourg harbour later that year. On July 7, 1858, the Cobourg Star noted that: “a vast amount of stone cutting has been accomplished… These carvings, together with the fine bearded face which forms the keystone of the arch are the work of Mr Thomas, contractor for the stone cutting, and certainly do him great credit.” This reference to a “Mr Thomas” led the hall’s restoration architect Peter John Stokes to conclude in an essay in the 1976 book Victorian Cobourg: A Nineteenth Century Profile that “the stone cutting contractor was no less than the firm of William Thomas, which executed the elaborate Corinthian capitals … bearded heads … lyre ornaments…” But why would Kivas Tully want to collaborate with his great rival, architect William Thomas? This question was answered in 1986 by James Leonard who found that it was his great-great-great-uncle Charles Thomas, a Welsh-born stonemason, and not the rival architect, who was responsible for the stone cutting at Victoria Hall. It is believed that Charles Thomas later went on to create stone carvings at the House of Commons on Parliament Hill.

One puzzle that has eluded historians is the identity of the “fine bearded face” on the keystone above the main doorway. It surely must have some symbolic or allegorical meaning, yet there is no record of who it is meant to be. Masonic secrecy at work, perhaps? It’s possible that the bearded face above the main doorway is a representation of the ancient Greek mathematician, Pythagoras, and is based on a classical bust in the Capitoline Museum. Even those who were indifferent geometry students in school can rattle off the famous Pythagorean theorem: for a right triangle, the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides. In Freemasonry, this theorem is also known as the 47th problem of Euclid, and a diagram of it is an important Masonic symbol that Sir Allan MacNab likely wore on his Grand Master’s apron.

Another clue to the identity of the “fine bearded face” is the fact that it is flanked by two carved lyres. Pythagoras was a skilled lyre player and it is believed that this helped him develop his theory of divine harmony, which holds that the universe moves according to mathematical principles, making a kind of celestial “music of the spheres.” Who better to crown the capstone of Tully’s harmonious building? Stonecutter Charles Thomas, a fellow Freemason, no doubt understood the significance of the “fine bearded face” and the symbols he was carving.

THEY DANCED ALL NIGHT

As work continued on Victoria Hall, another remarkable construction was nearing completion in Montreal: a bridge across the St. Lawrence River that was being hailed as the eighth wonder of the world. The Parliament of the United Canadas extended an invitation to Queen Victoria to attend the opening of this bridge, which would be named in her honour. The Queen was unable to attend but it was decided that the teenaged Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, should come in her stead. The news that the heir to the British throne would make the first-ever royal visit to North America caused huge excitement all across the Queen’s dominions. When the town fathers of Cobourg received word that the Prince of Wales would open their new town hall in early September of 1860, the pace of construction quickened.

Finishing touches to the ceiling frescoes in the upstairs music room were still being made when the royal entourage arrived in Cobourg harbour on the evening of September 6. A group of local men pulled the prince’s carriage past locally made festive arches from the pier to the speaker’s platform of the imposing town hall. During the speeches that followed, according to one newspaper: “The Cobourg folks rang out their huzzahs loudly and freely until sheer exhaustion compelled them to desist.” With the magnificent structure now officially named Victoria Hall in honour of his mother, the prince went inside so the celebration ball could begin. Champagne and music flowed, fancy dresses swirled and the town danced beneath the stunning frescoes. It was an evening the likes of which the town had never seen, and it would be a long, long time before it was equalled. “It was a very pretty ball,” wrote the prince to Queen Victoria. He must have enjoyed himself as it was reported that he danced tirelessly till three in the morning.

The next morning, the prince set out for Peterborough on the new railway. But upon reaching the start of the bridge over Rice Lake, the train stopped. The prince then boarded the steamer Otonabee for a trip to Hiawatha First Nation. Some suspected this had been arranged because the prince’s entourage refused to trust their charge to the rickety-looking bridge.

The town’s hangover would be long lasting. The collapse of the trestle bridge in the winter of 1861- 62 and the resulting failure of the railway line to Peterborough plunged Cobourg into a deep depression. The final price tag for Victoria Hall, which was to be funded in part by bonds from the defunct railway, was a staggering $110,000. It would be almost 80 years until the debt was paid off.

The town’s fortunes would eventually revive in the late 1870s, when Cobourg’s lakeside air and charming streetscapes, anchored by its Palladian town hall, made it a fashionable resort destination for wealthy Americans. Many of them built splendid summer homes, resulting in Cobourg being dubbed the “Newport of the North.”

Although the gamble of the town fathers didn’t pay off as they hoped it would, and Cobourg never ended up as Toronto’s rival, Victoria Hall is unquestionably Tully’s architectural masterwork. Its finely carved Corinthian columns support the town’s hopes; the seven lyres reflect the art, music and lyrics that grace its interior; the perfect symmetry of the two flanking wings promotes a harmonious community. Looking down from his perch over the main entrance, Pythagoras watches as royalty, judges, performers, politicians and promising high school graduates pass under his stony gaze. The building brings to life the mystical beliefs in “order, harmony and beauty” of the secret society to which Tully belonged.

The town fathers entrusted Kivas Tully with a daring dream, but history follows strange pathways. Victoria Hall with all its stately grandeur has become the heart of the community, steadfastly standing as the town’s cornerstone for over a century and a half.

Story by:

Hugh Brewster

Illustration by:

Carl Wiens