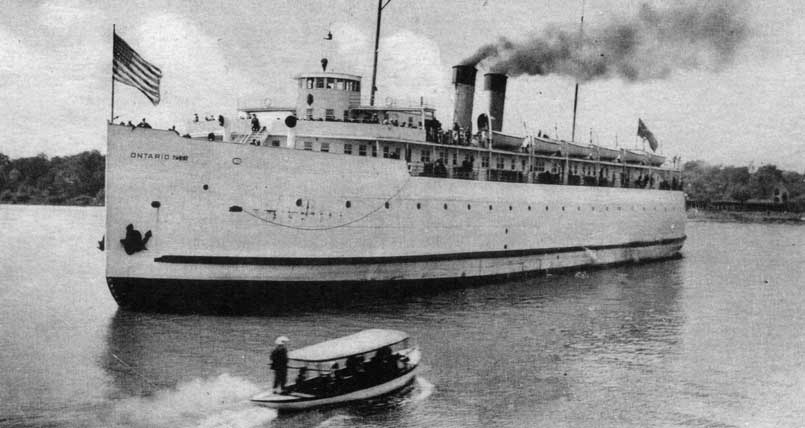

photograph of car ferry Ontario No. 2,courtesy The Cobourg and District Historical Society Archives

Seventy-five years ago this winter, a debilitating cold closed in over southern Ontario, bringing with it a once-in-a-lifetime event. From shore to shore, the giant mass of Lake Ontario fell silent under an icy cover.

There is a greyness all around them. They trudge across the frozen landscape, an Arctic pall engulfing their every step. The sky is grey; the ice beneath their feet is grey.As far as the eye can see: grey. But this is not the Arctic. It is no great distance from civilization, just a few miles from two great cities. The unusual thing is that the two cities between which this group stands are Toronto and Rochester. Because, you see, this landscape is deceiving. It is not “land” at all. It is, rather, a crust of ice that covers the surface of Lake Ontario. And this group is experiencing a once-in-a-lifetime event: the freezing over of the lake.

The winter of 1933-34 settled in early and hard. It continued at a furious pace throughout January and by February, driving in the country became treacherous. Farmers fell back to a reliance on their horses and sleds. With the new Hollywood film, Eskimo, playing in Toronto, residents of this region, affectionately dubbed Ontario’s “banana belt”, could be excused for thinking they had all just landed in some horrible northern movie set.

A WINTER TO REMEMBER

“Worst winter in years,” the Cobourg World declared in early February.“Big drifts isolate villages.”

“Almost every country road in this district was blocked over the weekend by heavy banks of snow as a result of the bitter northwest wind that blew icily across the county, making communications from Cobourg to outlying villages impassible to motor traffic, forcing farmers to fall back on the horse and cutter,” said the report.

The paper said roads to Roseneath, Harwood and other villages were in such bad condition that travellers chose instead to follow trails through the fields. “One farmer declared that the snow was so heavy that shovels were next to useless in digging out the roads. The local market on Saturday was seriously affected, few farmers being able to get into town with their produce. Business in town has experienced the worst period of slackness in many years, the farmers who usually come into town to do their shopping Saturday afternoon and evening were conspicuous by their absence and weather has been so cold for so long that local storekeepers are beginning to wonder what a dollar bill looks like.”

Reports from Prince Edward County, Belleville and Trenton told the same story. Temperature records were smashed. Belleville hit -31°F. Temperatures remained below zero for three days straight in some communities. And in the days before Celsius measurement, “zero” really meant something.

Hospitals reported record numbers of frostbite victims. Shivering residents set fires to thaw frozen pipes and overheated their stovepipes. Water mains burst. Frost snapped telegraph wires.

Police departments opened their cells to vagrants. This was, after all, the Great Depression and the jobless roamed the countryside and city streets. The Cobourg chief estimated he had housed 550 since the first of the year.

How cold was it? It was so cold, said Cobourg World, that an electric pump froze in the basement of Dr. H. Crawford’s Marmora home. The resulting buildup of pressure in a large water tank hurled the vessel into the kitchen above. This in turn sent the stove, which was immediately above the tank, to the ceiling, wrecking it beyond repair.

But that’s not all. A coal fire in the stove was scattered across the floor by the blast. Luckily, the water that gushed out of bursting pipes extinguished the fire before more damage could be done.

Then the tank descended again to its original position.“ The bottom of the tank was damaged but was later repaired,” said the newspaper. “Fortunately none of the occupants of the house were near at the time.”

Think that’s weird? Perhaps. But arguably the strangest quirk of nature was the one that occurred on the body of water that so influences daily life in our region.

The Toronto Globe reported: “Lake Ontario froze over for the first time in 60 years or more.” The Telegram added: “The 45-mile stretch between Cobourg and Rochester, N.Y., was a solid mass of ice.” The news was so big it made the New York Times.

The surface area of Lake Ontario is smaller than any of the four other Great Lakes, but its average depth of 283 feet (86 metres) places it second only to Superior in that category. At its deepest, Ontario’s bottom plummets 802 (244 metres) feet down. Its volume is 393 cubic miles (1640 cubic kilometres), more than three times that of Lake Erie.

This is why Ontario rarely freezes while Erie, which sits in a slightly milder winter zone, frequently freezes. Dave Phillips, senior climatologist for Environment Canada, explains that due to Ontario’s depth as a ratio to surface area, water from beneath the surface is more apt to replace the surface water and keep it warmer in winter. Erie has more of its volume exposed and cools faster, he says.

WHEN THE ICE ROARED

In the 91 years Carroll Nichols has lived on the shores of Lake Ontario, only once does he recall the bay near his home freezing over solid enough to hold a skater – February 1934.

“My father was at the barn,” recalls the life-long Port Hope-area resident. “He came running to the house, all excited. He’d seen the neighbours skating on the lake. So my father and I grabbed our skates and we went out and we skated on the lake that afternoon. It’s a bit of a bay right there. It was the only time… I remember seeing it fit to skate on.”

“A lot of apple trees froze dead that year,” says the retired farmer/electrical contractor and local politician.

That night, a bitter north wind howled down on the region and Lake Ontario began, reluctantly, to give up its massive cloak of ice.

“You could hear the roaring of the ice,” Nichols says, the sound still fresh in his ears even threequarters of a century later. “It was just as if the ice was blowing up. It broke up and piled up on top of itself as it crashed back out into the lake. There was this tremendous thunderous roar all night long.”

“It’s the only time I ever experienced anything like that.”

By morning as the wind subsided, the Nicholses, father and 16-year-old son, looked out over the lake. The ice was gone.

“It gave you a funny feeling, knowing that you’d been skating out there just a few hours earlier and now it was open water.”

Carroll Nichols has lived on his Port Hope farm for his entire 91 years. Nichols recalls the night in February 1934 when “… you could hear the roaring of the ice. It was just as if the ice was blowing up… There was this tremendous, thunderous roar all night long”.

THEY WALKED ON WATER

Charles E. Redfern was born in Lakeport in 1869 and grew up drawn to the great waterway on which his village bordered. At the age of 16 he took a seaman’s job on a windjammer and at 23 he was awarded his first command, the coal and grain freighter Albacore.

Redfern was a strapping young man of six feet, 230 pounds when he went to work on the ships. By the time he was ready to take his first command, the pride of the waterways were the Ontario Car Ferry Company’s sister vessels, Ontario No. 1 and Ontario No. 2. Their hulls reinforced with steel plates, both were able to break through ice and plied the lake, between Cobourg and Rochester, winter and summer, hauling coal, cars and passengers.

In 1915 Redfern took command of Ontario No. 1. In 1926 he took over Ontario No. 2. Between the two ships, Redfern would put in 21 years with the Ontario Car Ferry Co.

Redfern encountered all kinds of weather during his career: hurricane-force winds, 70-foot crests breaking over the captain’s cabin, blizzards and ice formations three feet thick on the ship’s bridge. There wasn’t much Captain Redfern hadn’t seen and overcome on the lakes.

Until February 1934, that is.

The week of February 5 to 9, Redfern and his crew had battled ice the entire trip across the lake, from Cobourg to Rochester and back again. Longtime residents told Cobourg’s Sentinel-Star newspaper the ice bordering the shore extended out farther than at any time they could recall since 1918.

Redfern told the paper he’d recorded temperatures of -30° F. on the bridge of Ontario No. 2 and declared the crossing that week the coldest he had experienced. He said ice was at least four inches thick right across the lake and even the floating ice had congealed into a solid mass.

“A dog could have walked from Rochester to the Canadian shore if he avoided the air holes,” according to Captain Redfern.

Redfern’s 318-foot-long vessel had been built in 1915, its reinforced hull constructed to navigate ice floes four feet deep. Yet on this occasion the ice threatened to stop the ship dead in its own wake. Several times the captain ordered the ship halted and backed up in the small openings it was making in the ice. Then he would order that it smash forward at full speed so that its full 5568-ton bulk could be used to bust through an ice jam.

The captain reported dense steam rising from the few air holes that existed in the solidifying field of ice, adding to the difficulty of navigation.

“Byrd and the boys in the Antarctic had nothing on us,” quipped Redfern. “It was real hard going and I know I don’t ever want to see it any worse.”

It did get worse. That Saturday, February 10, Ontario No. 2 found itself unable to break through the solid and thick floating ice encountered on its way to Rochester. It dropped anchor and held on until the icefield passed, a period Redfern estimated at six or seven hours.

Conditions were not improved on the return leg of the voyage. The Rochester Democrat and Chronicle reported later that day: “The car ferry Ontario No. 2 lies 12 miles off the Port of Rochester with its nose firmly imbedded in solid ice and unable to move in any direction.”

Shortly before noon, said the newspaper, Redfern wirelessed Toronto of his predicament. “‘All is well aboard,’ was the assurance given by the captain who found himself ice-bound for the first time in his 40 years of navigation on the Great Lakes,” it reported.

The U.S. Coast Guard cutter Eagle was assigned to rescue the trapped ship. But the cutter’s oil lines had frozen up and by the time they were thawed, ice was so heavy in the Genesee River it never made it out of port.

According to the Cobourg World, Ontario No. 2 was 15 miles out from Rochester when the huge cakes of ice halted further progress. Unable to move forward or backward, crewmen apparently amused themselves by clambering off the ship and walking around the lake’s frozen surface. Far from shore, an eerie greyness enveloped them, a greyness with the power to render the huge vessel insignificant and vulnerable.

That evening, a stiff wind arose, breaking up the ice sufficiently to allow Ontario No. 2 to proceed into the Port of Cobourg the next day.

The weather moderated for a few days before the cold struck again with full force.

On Friday night, February 16, Ontario No. 2 again became mired in the ice. “Held helpless in the grip of Lake Ontario ice,” said Cobourg’s Sentinel-Star.

This time Captain Redfern had navigated to half a mile off Summerville lighthouse outside Rochester. The Eagle was again ordered out to the rescue but this time it was darkness, and not the icepack, that drove the cutter back to shore.

News reports said drift ice carried by a northeast wind piled up two to three feet thick around the Ontario and blocked its passage.

Early Saturday, the Ontario broke through the ice under its own steam and finally reached the Port of Rochester just before 9 a.m.

“Capt. Charles Redfern, commanding the ship, said he was getting used to the experience of getting frozen,” said the Sentinel. “‘At no time were we in any danger,’ he said. ‘We had ice all the way across but did not lose way until we struck the heavy shore ice about 3:30 Friday afternoon.’”

COULD IT HAPPEN AGAIN?

Satellites were first used to observe the Great Lakes in the 1980s, so whether Lake Ontario froze over prior to the ’80s has to be based largely on eyewitness accounts. And eyewitnesses are notoriously fallible.

Science has been slow to study Great Lakes ice conditions. Until the winter of 1959-60, no hydrometeorological observations had been made on any of the lakes during winter, according to a 1961 report by the University of Toronto’s Department of Geological Sciences and the Canadian meteorological branch.

Yet the dream of winter navigation was sparking further study to understand how and when they were likely to freeze. Data obtained from icebreakers was useful but it was a major step when aerial reconnaissance flights over Lake Ontario began in early 1960.

The freezing over of Lake Ontario is rare, the researchers went on to say, but information obtained from weather observer A.W. Hooper and a former employee of the Ontario Car Ferry Co., R.S.Martin of Cobourg, satisfied them that the great freeze had indeed occurred during the winter of 1933-34, perhaps “to a thickness of half a foot or so.”

Environment Canada’s Dave Phillips says there is strong anecdotal evidence of how thoroughly the lake froze that season. “There were stories of people skating on the lake, losing sight of land and still finding the ice in good condition,” he says. “The ice was said to have made incredible sounds as it cracked and moved.”

One report had a group of people depart Toronto intent upon walking all the way to Rochester. But as they lost sight of land their resolve began to disappear. When all you can see as you turn in a circle is grey ice and grey sky, their reluctance seems quite understandable. They returned to shore.

There have been suspicions that the lake “nearly” froze again in the late 1970s and again in 1993. Other less reliable stories have it freezing across in 1912, 1893 and 1874. But the strongest evidence of the big freeze remains that of 1934, likely about February 9 and/or 10.

Glenn Johnson, meteorologist for 13WHAM TV in Rochester, says it’s “nearly impossible” for the lake to freeze over entirely, but agrees the evidence is strong that it happened in 1934. It may also have happened in 1855, he says. “From a scientific standpoint the only way to confirm it is via satellite,” says Johnson. “But the anecdotal stuff, it’s kind of cool, isn’t it?”

With climate change warming average annual temperatures, are we ever likely to see a repeat of the winter of 1933-34? Will Lake Ontario ever freeze over again?

“My sense is that it’s still possible,” says Phillips. “Forces will still sometimes come together to create the conditions. There are those months you’ll have a Siberian cold spell that lasts three weeks, low winds. Yes, I think it could happen again.”

A note on sources: Cobourg author Ted Rafuse’s book, Coal to Canada, provides a description of the car ferries Ontario No. 1 and No. 2 and background on Captain Charles Redfern.

Story by:

Gary May