A story of HMCS Skeena; of the battles fought and of the lives lost, and of a tradition spanning generations

SEAFARERS BELIEVE A SHIP IS A LIVING THING. BUT WHEN A SHIP IS GONE, DOES ITS SPIRIT LIVE ON? Lieutenant (Navy) Chris Barker knows it does. He’s the Executive Officer of 116 Royal Canadian Sea Cadet Corps Skeena in Port Hope. The corps is named for HMCS Skeena, wrecked off Reykjavik in 1944. You might call Chris the prime caregiver of the spirit of Skeena.

HMCS Skeena was one of the first two ships commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy in 1931, along with HMCS Saguenay. During the Second World War, HMCS Skeena fought in the Battle of the Atlantic, escorting dozens of vital merchant marine convoys. She rescued the crews of four ships torpedoed by German U-boats, and shared credit for sinking U-588 off St. John’s in 1942.

It was the call of duty, heartfelt and simple. But a wave was building. Isaac Unger, brother of one of Skeena’s casualties, wrote a book, Skeena Aground about the wreck. A copy made its way to Chris.

Skeena’s distinguished service ended terribly. On the night of October 24, 1944, in a fierce storm, she dragged her anchor and was wrecked in a cove at Viðey Island, just off Reykjavik. In the confusion, 36 of her crew of 151 abandoned ship, but Skeena’s lifeboats were destroyed. Fifteen men died. Skeena was badly damaged, and later scrapped.

“I THINK THAT’S THE TRAGEDY OF IT ALL,” says Chris Barker. She was a workhorse. And in one night, it was all over.” Chris, a husky guy with a neatly trimmed beard, is wearing a t-shirt, shorts and sneakers and is sitting at a table on “the deck” at Skeena Hall in Port Hope, doing what he does best: telling Skeena stories. Fifty-six and happily retired, Chris devotes himself to Skeena (the corps) and Skeena (the ship) with a passion. A “Cobourg boy” who dreamed of going to sea, Chris began his career as an engineer on Great Lakes freighters. Later, he joined the naval reserves in Toronto. Moving home in 1993, he transferred to the local sea cadet corps as Training Officer. His role: teaching seamanship to kids from 12 to 18 years of age.

In an old red brick church, 116 Royal Canadian Sea Cadet Corps Skeena occupies a large hall, lit by gothic windows minus the stained glass; the walls are covered with flags and memorabilia. The lobby functions as a shrine to Skeena. A hand-painted thermometer records the success of a recent fund – raising campaign to send cadets to Iceland. On the wall is a painting of the second Skeena, a Canadian destroyer escort active from 1957–1993.

The decommissioning of that ship was a fateful moment for Chris. “That’s when I said to my CO, ‘The cadet corps will be the last ship’s company to carry on the name Skeena and to remember these 15 sailors’.” Something had to be done. “I suggested that we start a new tradition, and on the closest Tuesday to the 24th of October, let’s do a Remembrance service.” That first service was held on the 50th anniversary. “We assembled the cadets on the deck. I had the kids place 15 poppies in front of a picture of the ship. And we recited the Naval Prayer.”

It was the call of duty, heartfelt and simple. But a wave was building. Isaac Unger, brother of one of Skeena’s casualties, wrote a book, Skeena Aground about the wreck. A copy made its way to Chris. A local Skeena veteran began showing up for the annual ceremony. In 2000, survivors of the wreck held a reunion in Port Hope. They came again in 2001.

“When the veterans started coming back, they started bringing us artifacts,” says Chris, gesturing around the hall. “They’d say, ‘I’ve had this for 60 years… it’s better that it be here, because this building now is Skeena’.” The ‘artifacts’ include the flag, and the wheel of HMCS Skeena.

THE SKEENA VETERANS WERE GUARDED with their stories. But a former RCAF chaplain, a Reverend Davidson, confided to Chris: “Out of all the men that I buried over in Iceland, it was the Skeena funeral that still affects me to this day.’” Chris pauses before echoing the Rev. Davidson’s words, “‘You cannot imagine the size of the hole in the ground for so many men.’”

“That’s when it hit me,” says Chris, still visibly moved. “Some of these boys were probably 18, 19, 20 years old. You’ve survived the war, the loss of your ship and fifteen of your crewmen. You’ve hiked up to the cemetery. You’ve got borrowed clothes on from the US base, and you’re looking at 14 men in a hole.” Chris shakes his head. “So that’s when I pulled some men aside and said, ‘you know in 2004, that’s the 60th anniversary of the loss of your ship…’”

Chris proposed the veterans should go back to Iceland. Their responses, he says, were blunt: “‘NO, NO, there’s nothing there; why the hell would I want to go back there, with nothing but snow and ice.’” But Chris’s mind was made up. “Well, the hell with ya!” he said. “If you guys don’t want to go, I’m going to go, and go over to Viðey Island, and see the cove, and I’m going to go see the gravesites.”

The wave was cresting. A group of veterans, families, wives and widows took up the call. The Skeena corps raised enough money to allow two cadets and an escorting officer to make the trip with them. Chris paid his own way.

Chris’s memories of that trip are vivid. “We had a beautiful service. The veterans and cadets laid plaques on all the graves. I remember one man standing by his brother’s grave, saying he remembered his brother going out the door in Montreal.” He never saw him again. Another veteran hugged Chris, swore in his ear, and said, “That’s the first time I’ve cried in 60 years.” Then the vet saluted him. Chris remembers the veterans’ astonishment when they first laid eyes on Viðey, a grass-covered mass of rock only a mile from Reykjavik – so close, and yet so far.

The experience was memorable for the cadets too. “It was just so touching,” recalls Brittany Ashby, who wrote an essay about Skeena to earn her place on the trip. “And it’s something that my generation would never experience unless you were there in the moment.” Just 17 at the time, Brittany did something unusual for a disciplined cadet: she ‘stole’ Isaac Unger’s book from the Port Hope Library, brought it to Iceland – then brought it back. “I had each of the veterans sign the book, and then I went to a town meeting and stood before the mayor, and the librarian, and kind of admitted to defacing their book in a way that honoured the veterans.”

After that 60th anniversary trip in 2004, Chris thought the story was done. “We get back from Iceland, and I’m thinking, the book’s now closed… but that’s when they found the propeller!” On the trip, one veteran had recalled throwing fuses from depth charges overboard as Skeena foundered, to render them harmless. Taking no chances, Icelandic officials dredged the site and discovered Skeena’s propeller. Thinking it might make a fitting memorial, they contacted Chris Barker. Back he went to Iceland in 2005, this time with his young daughter in tow, to consult on a suitable site. A year later, he was back yet again, with a group, for the unveiling. All this on his own time, on his own dime.

“Norm Perkins, Ted Maidman and their wives, plus Swede Steinhoff, and Ed Parson’s widow Olivia…” Chris names his fellow travellers on that 2006 trip. The ranks of the veterans were thinning. Ted Maidman had cancer and would die just weeks after the trip. In his eulogy, his family thanked Chris for taking him back to Viðey Island. The late Ed Parson’s return to Viðey was of a different kind: at the dedication of the monument, Olivia told Chris “Ed is with us.” Chris replied, “Of course he is,” thinking it a figure of speech. “No, I mean really with us,” she said – revealing a container of Ed’s ashes. His last wish had been to have Chris scatter them where Skeena had foundered. Chris complied, scrambling among the wet rocks in his dress uniform. Later, he told Olivia “Ed is still with us,” gesturing to his uniform, streaked with windblown ashes.

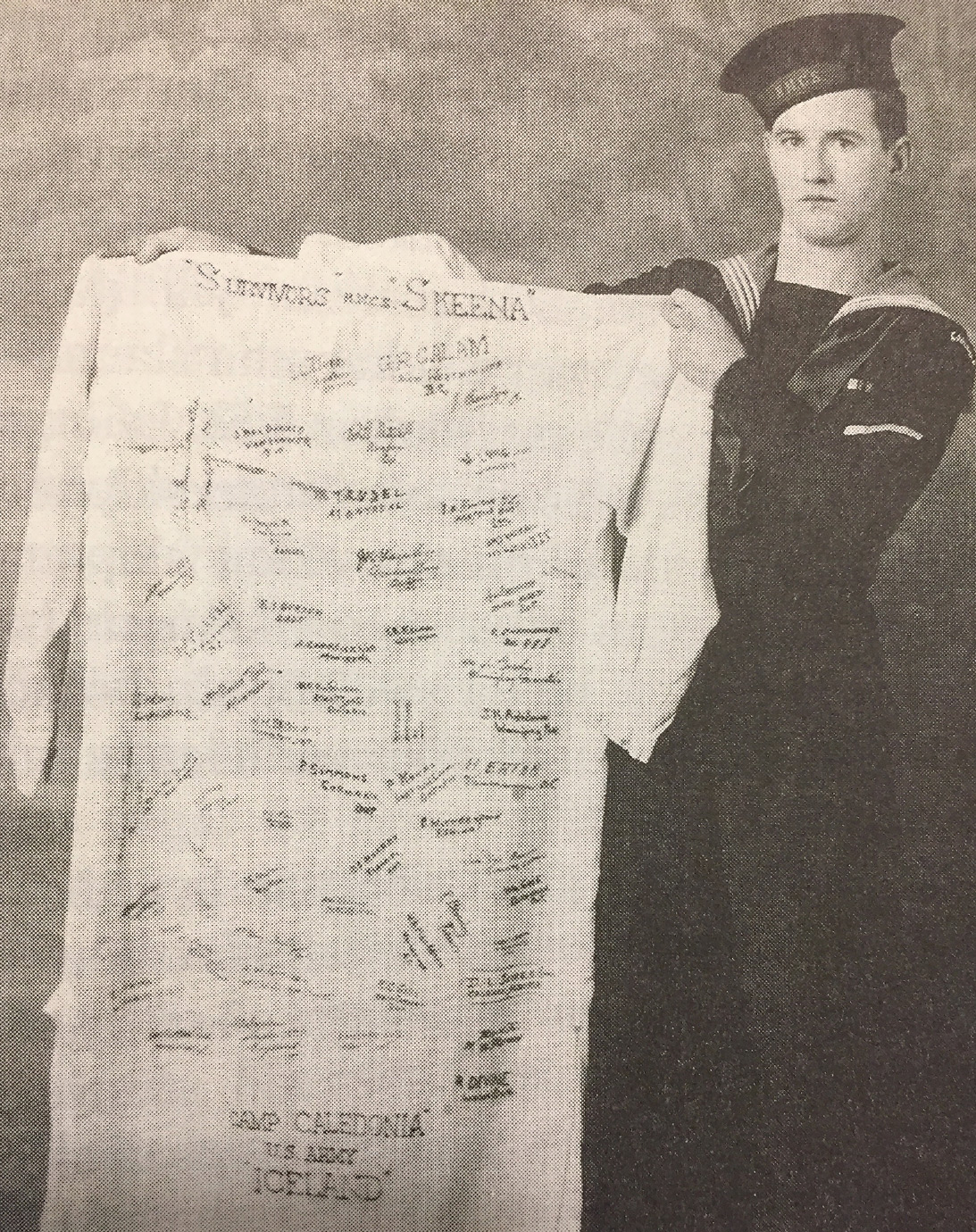

In the 15 years since that last visit, Skeena in Port Hope has continued to hold ceremonies. Sometimes no one from outside the corps shows up, “But that’s okay,” says Chris. “We’re doing it for the cadets.” They still collect artifacts – a hospital gown worn by a survivor in Reykjavik, signed by his shipmates, is a treasured relic. Of the veterans of the HMCS Skeena, Chris knows of only two who are still living. Neither is up for another trip to Iceland. But Chris is going back.

“In 2006 I made a statement to Ted, Norm and Swede: ‘Rest assured, I will be here on the 75th anniversary,’” says Chris solemnly. “It was literally just over a year ago that I approached our navy league branch here and asked, ‘What do you think about taking all the cadets to Iceland for the 75th?”

Chris grins. “The budget was between a $150,000 and $160,000! How in the world were we going to raise that kind of money in a year?” They did it, though. Chris and his colleagues made the rounds of the service clubs in uniform. Cadets, families, businesses, and the community radio station all pitched in. A “Catch the Ace” lottery raised $103,000. For Chris, it was a Skeena miracle. “We did a breakfast launch on September 25th. By July 21st when the ace was found, it was just 300 days. We raised over $500 a day! And July 21st was exactly three months before we were to depart!” Another big wave was building.

Today, the story of the Skeena is a little better known than it once was, at least in Iceland. The young captain of the ferry to Viðey Island can point out the fiord to the north where Skeena’smen washed up, covered in oil, some living, some dead. From the ferry dock, a rugged trail leads across the largely empty island to the Skeena monument: the propeller dredged from the cove. It sits on a rock chosen by Chris and his daughter back in 2005. Nearby is a plaque remembering local captain Einar Sigurðsson who was made a Member of the British Empire for leading a daring rescue of Skeena’s survivors.

Dianne Kukavica, the current Commanding Officer of 116 RCSCC, was the escorting officer on the first trip, back in 2004. It was Dianne who played “Last Post” at Fossvogur Cemetery. “Every year at our unit Remembrance service, we ring the bell once for each sailor aboard HMCS Skeena who perished,” says Dianne. “We hold the service to keep the memory of our namesake alive.” But this year will be different: “This is the first time in 25 years the service won’t be in Port Hope – it will be there. I think for the next few years, the services will be more cadet led, because they will now have that understanding.”

Brittany Ashby says, “The experience that I had in 2004 won’t be repeated, but the story continues in time. It’s almost taking it full circle… you take a group of veterans and two cadets; now there are cadets and two veterans too old to travel. It’s keeping alive what the navy is, what the stories were and how they were represented.”

Chris keeps in touch with everyone connected to the Skeena story. Brittany lives in Thunder Bay, but he takes her to lunch when she’s in town. Ottar Sveinsson, an Icelandic author who wrote a book that mentions Skeena, texts regularly with plans for the autumn visit. 97-year-old Peter Chance, who was on the bridge of the Skeena on the night of the wreck, emails Chris with detailed recollections. Chris checks in on Norm Perkins, the last veteran to attend the annual ceremonies in Port Hope, as though he were a beloved uncle. Chris knows where the bell of the Skeena resides (HMCS Haida, in Hamilton) in case he needs to borrow it. He even has a line on the possible resting place of Leading Seaman Blais, whose body was never found.

CHRIS KNOWS HE’S NOW A PART OF THIS STORY. It’s a challenge to his natural modesty, which he manages by making his efforts about something bigger than himself. The President of Iceland invited him to lunch on the upcoming trip; Chris managed to turn it into a lunch for the whole cadet corps.

In October of 2019, Chris Barker, Dianne Kukavica and their colleagues will accompany 22 cadets, including Chris’s teenaged son, to visit Viðey Island for the 75th anniversary of the sinking of Skeena. At Fossvogur Cemetery, the cadets plan to do gravestone rubbings to bring back to Skeena. The roll will be called, as it is every year “on the deck” back home. Dianne is already imagining what she’ll say to the cadets: “This is why we’re doing this. This is where they ran aground. There are graves here.” Chris’s son may play “Last Post” this time. Tradition grows.

Skeena’s remembrancers will be surrounded by the graves of dozens of Canadians, among hundreds of service personnel and merchant mariners from around the world. These are but a few of the casualties of the Battle of the Atlantic, who died at the remote edge of a global war. On that hallowed ground, Chris Barker, Lt(N) a Cobourg boy who once dreamed of going to sea, prime caregiver of the spirit of Skeena, will hear again the stirring words that motivate him, to this day: “You cannot imagine the size of the hole in the ground for so many men.”

Lest we forget.

Story by:

David Newland