The respected political commentator and journalist, who spends every summer with his family at their home in the County, reflects on the life cycle of trees and the future of forests.

David Frum is saying something to me about trees – I think. He’s not a very loud talker to begin with and right now he’s bent over Lucia, my four-month-old goldendoodle, ruffling her apricot scruff and occasionally glancing up to gesture towards the forested corner on the far side of the property. The pup is happily weaving figure eights around his legs with her long training leash. “David…” I warn, but he cuts me off with a smile, shaking his head. “It’s fine.”

When he stands upright again, I can confirm David is indeed talking about trees, but Lucia’s design is becoming more intricate by the second. Just when I’m certain that David will succumb to the impossible tangle, he steps up and out neatly, freeing himself. He’s a longtime dog guy – these moves are second nature. The pup takes advantage of her new freedom, pouncing onto a delicious looking butterfly who has landed unsuspectingly in a nearby patch. A win, a loss.

Finally, I could pick up what David was putting down. He’s been pointing out the acre of dense conifers that the first owners of our home had planted in the early ’90s on the northeast corner of the property.

“You know,” David says, “those conifers could eventually be replaced by hardwoods, like oaks, that would grow up among them and take over, using the current trees for nutrition and creating a healthy forest that would endure far longer than what’s here now.”

“Seriously?” I say, totally interested. “Like, I love this forest, but I think the trees were planted too close together and we lose a few every winter and maybe they’re not actually doing that well…” I’m blathering. Note to self: learn more about trees.

“It’s the way to go,” David says.

We met in 2019 at The Old Third, our mutual friends’ winery in Hillier. In those days, they’d host regular dinners after hours, in their beautifully restored barn. But the real magic came later in the night, when we’d move upstairs to the third floor and the little modern sitting area I nicknamed “The Mick Jagger Room.” It was outfitted with Persian rugs, angular furniture and framed with glass-panelled railings that let the majesty of the soaring barn ceilings envelop the floating floor. Next to the yellow leather sofa, the hollow side table housed a small collection of books bracketed by the Kama Sutra and Infinite Jest, the breadth of content between which informed our conversation and, along with the help of some deliciously dusty bottles from near and far, qualified us for some serious, no-messing-around karaoke. We likened this period to the Belle Époque and shared the fruits and joys of our labour with great relish. And until the era of Covid took hold, it was the best of times.

DAVID, HIS WIFE DANIELLE AND THEIR SON NAT are in the barn tonight and I’m delighted. In an interview I gave to the XO Project earlier that spring, I confessed in print that David Frum was the “County person” I most wanted to meet that year. Cosmically, we were bound to cross paths sooner or later: Danielle’s family bought a home in Prince Edward County more than thirty years ago, and the Frums drive up from Washington, DC every summer and stay until fall. It’s important to note at this point that I’m just about as far as it gets from an expert in the political sphere – I don’t even dabble – but David Frum isn’t just the guy who was called to Washington as a speechwriter for the George W. Bush administration, he’s not just the guy who (for better or worse) is credited with the phrase “axis of evil,” and he’s not just one of Trump’s most prominent anti-fans. He’s a prolific writer on politics, policy, art, lit and history. He’s a senior writer at The Atlantic and contributor to MSNBC, with ten books authored and co-authored (three of them New York Times bestsellers), and innumerable publications and appearances to his credit, from The Wall Street Journal to CNN. Seeing beyond those formidable credentials, I also happen to be a human detector for interesting/cool/fun people, and within an hour of hanging together in the Mick Jagger Room – the Frums were all on my list.

At some point, I took the stage, a little platform facing the sofa, the entire barn stretched out gloriously behind me. Holding the mic keenly with both hands, I sang the first words of my signature karaoke tune, the 1983 anti-war hit “99 Red Balloons” by Nena. The story goes that guitarist Carlo Karges was at a Stones show in West Berlin when the band released a bunch of balloons. Carlo watched as one drifted over the wall into East Berlin and imagined their radar mistaking it for an enemy plane. David was in his 20s in the Cold War era and decades away from front-row politics, but his eyes definitely lit up when I began “Hast du etwas Zeit für mich?”, perhaps stirred by the geopolitical associations on which he’d built his career.

Maybe, the hardest part about working in politics is the uncertainty of the outcome; the inability to know with conviction that the way you’re facing is the right direction. While I lack the courage to deal with these types of circumstances and these types of stakes, people like David seem to have a different capacity. They gather the best information they can from the best minds available, process, decide and act. Whatever the outcome, it’s a lesson that guides the next decision. During his time in the White House, David was considered to have brought intellectual gravitas and notable policy influence to the George W. administration. At the time, he was a strong supporter of the Iraq War – though in later years he was said to have regretted this endorsement. Sometimes, I guess, in the fog of war, you can’t see the forest for the trees.

“There’s something about David’s trees-within-trees strategy cartwheeling in my mind; something about strong oaks coming up behind soft pines that once dominated. About hindsight laying the groundwork for foresight.”

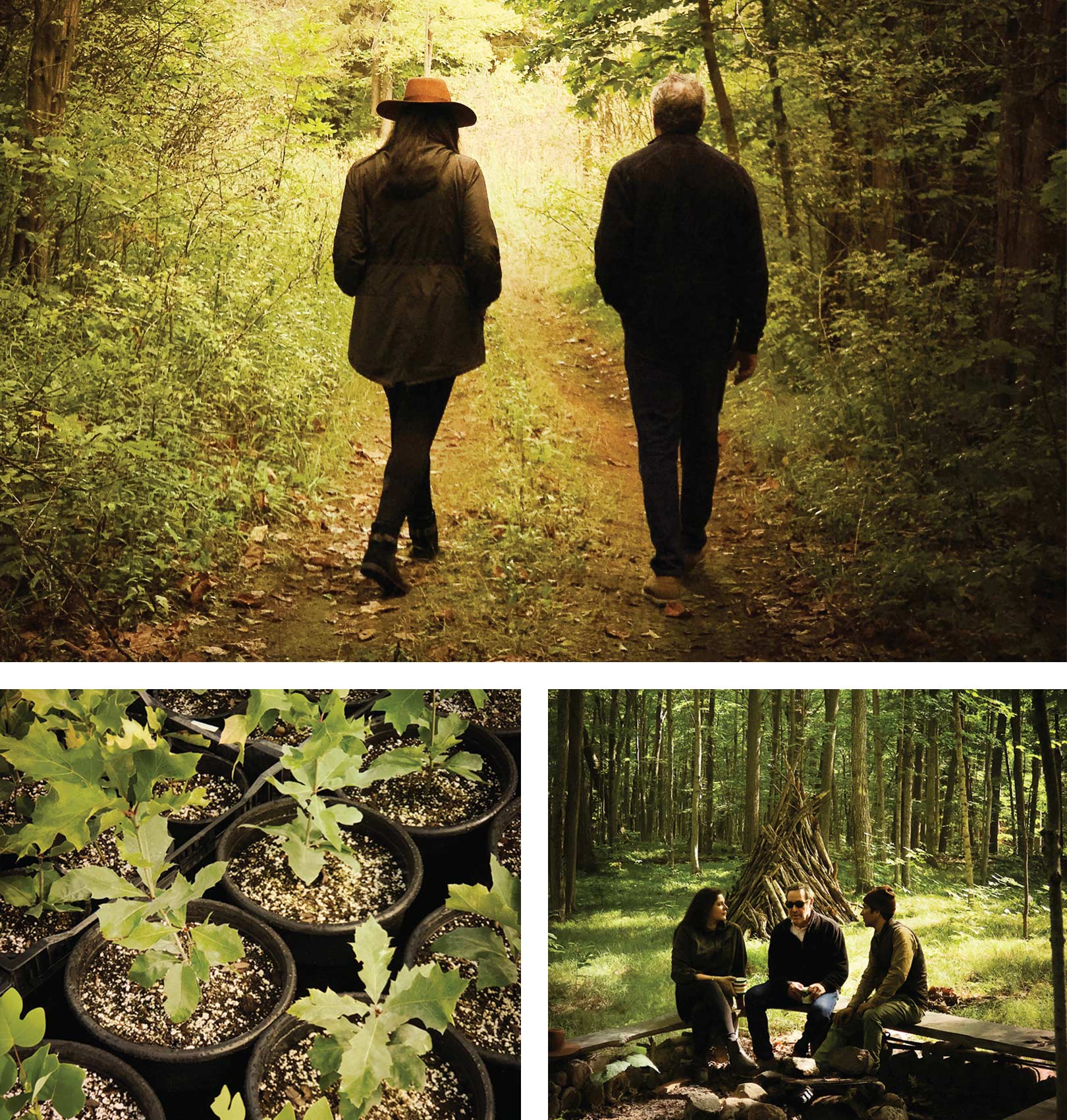

“I ALWAYS FORGET YOU’RE SUPPOSED TO WALK DIFFERENTLY IN THE WOODS so that you don’t trip on all the roots,” I say, lifting my feet comically and taking David’s arm to pull myself up to the next foothold as we follow our guide off-trail while walking through the approximately three hundred acres of forest at Edwin County Farms. “Don’t forget to do it too, David. Like John Cleese…”

David doesn’t miss a beat: “The Ministry of Silly Walks,” he confirms.

We’re hanging out with tree aficionado Nick Sorbara, who runs the farms and got really deep with me about his conservation goals in our interview for last year’s Spring issue of Watershed. Having ID’d David as a tree guy, it seemed like this was the right place and Nick was the right guy to take our conversation to the next level. “So looking forward to this,” Nick says. “I was talking to my dad and he also didn’t know you were into trees.” Nick’s dad is Greg Sorbara, the inceptive force behind the development of The Royal Hotel, and interestingly, an old friend of David’s.

“I’m at risk of overstating my expertise here,” David protests. “I made a stray comment to Lonelle and this happened.” David doesn’t know yet – that’s my modus operandi.

As the three of us walk towards the greenhouses where rows of small trees sit, I remind David of what we were discussing the other day.

“This part of the world was once very heavily farmed,” David contextualizes, “and when you farm, of course, you remove the tree cover. Over the years, many of the farms were abandoned or fell into neglect…”

“And some became megafarms,” Nick interrupts.

“Some became megafarms.” David nods. “Where we live in Wellington, for example, was once a tomato-canning plant. The soil was exhausted so we began experiments trying to reforest it – so I had to learn something. The land was bald and it was very sunny. Some trees grow in the sun and others don’t, so we began by planting pine trees, which like bright sunlight. As the pines grow, they provide canopy and then underneath that, leaf trees can begin to sprout. The leaf trees are stronger competitors, and over time will rise beneath the pines, crowding them out.” David pauses. “So, we’ve planted pines at our place with a view that when they get bigger, we will plant hardwoods … but that’s going to be a project for my son, right?”

Nick’s more hyped up now, because David’s question anticipates the project that’s actually happening on the ground in front of us. “So, you don’t have to wait for it to be your son’s thing, because what we’re learning here is how to grow hundred-year forests in thirty years.” He points to a substantial seedling in a pot near where David is standing. “This is an oak that came from an acorn from this property – it’s only a few months old.” Everyone’s wowed.

“I’ve planted oaks that are five years old and not more than three times the size of that one,” David says in disbelief as we hop into Nick’s 4×4 and head out on the dirt road toward the deep interior of the woods. As we bounce along, Nick is pointing out his favourite shagbark hickory tree on the right and showing us how they are working to remove tonnes of invasive buckthorn on the left.

Nick explains that he’s been watching a company that’s experimenting with the best way to grow trees. He talks about special pruning pots with holes for the roots and growing “supertrees” by carefully choosing seeds selected from exceptional mothers. He calls it rewilding, not reforesting, and by the time we unload ourselves and head out onto the first trail, we’re tingling with new ideas.

WE’RE IN A CLEARING DEEP IN THE WOODS sitting around an unlit campfire on benches of wooden slats propped up on rough stumps. We’ve become a little quiet – reflecting on the magnificence of the forest around us, the streaming sunlight flooding through gaps in the towering trees. David breaks the silence. “I came here thinking I knew a little something about trees and I realized no, I don’t…”

“I feel that way too,” Nick says. We’re surrounded by tall trees, but the forest is still young. Nick and his people have big ideas and plans, and they’re learning as they go.

Suddenly, we’re telling stories and laughing. “About a dozen years ago Danielle co-wrote a cookbook with our friend Anne Applebaum and they photographed at Anne’s house in Poland with a team of very skilled photographers who didn’t speak great English. Ultimately, the one Polish word she ended up mastering was blizszy, which means ‘closer’ – the shot always needed to be closer.”

“Danielle is one of the funniest people I know,” I chuckle, remembering her genius karaoke performance that night – definitely a form of art-comedy.

David shifts a little on his log seat, smiling. “The late Christopher Hitchens wrote a notorious article for Vanity Fair just before his death called “Why Women Aren’t Funny” and it caused a firestorm, as you can imagine. We had lunch together shortly afterwards, and I said to him ‘What about Danielle? Danielle’s funny.’ ‘Yes, Danielle’s funny,’ he said, ‘much funnier than you, old chap.’” I don’t entirely agree with Hitchens here: David’s funny – his humour is just quieter, more sincere; Danielle’s is boisterous and vibrant.

I love this day, it’s perfect middle-of-the-woods, fireside stuff.

“Speaking of Hitchens,” I segue, “do you feel like you’ve crossed the floor?”

David thinks for a short moment. “No, I’ve become more detached from those kinds of considerations.” He describes a parable involving a bear who would stop off on the way home from work and have a glass of mead, which eventually turned into several glasses. He would come home and knock over the furniture and put his elbows through the window and his wife was very distressed, his children very frightened. At length, the bear saw the error of his ways, became a temperance advocate and preacher who would go around the town telling people about the evils of drink; and to demonstrate how good he felt, he would come home and knock over the furniture and put his elbows through the window and his wife was very distressed and his children were very frightened. “The moral of the story,” David says, “is you might as well fall flat on your face as lean over too far backwards.”

It puts me in mind of a work by American playwright Lee Blessing, based on an event that happened on July 16, 1982. The chief American and Soviet arms negotiators, Paul Nitze and Yuli Kvitsinsky, decided to take a walk in the woods near Geneva. As they walked, they talked about themselves, their families and lives as well as the complexities of the negotiation before them. Speculating that if the Soviet Union withdrew some of the missiles they’d already deployed and the Americans withdrew some of the missiles they were planning to deploy, it would essentially stop the arms race. With this paradox before them, they drafted a proposal for arms reduction that was later rejected by both governments; but through the exercise, they broke the conversational impasse and reached new insights together that were meaningful in the long term. There’s something about David’s trees-within-trees strategy cartwheeling in my mind; something about strong oaks coming up behind soft pines that once dominated. About hindsight laying the groundwork for foresight.

WE’RE OUT OF THE WOODS and back up at the farm, near a massive old oak bordering Edwin’s flower gardens. We’ve got a shovel, a trowel, gloves, wood chips, and water. “The old adage is that the best time to plant a tree was twenty years ago – and the next best time is today,” says Nick.

“Okay,” I say. “Are you ready, David?”

“Ready,” he says. “Let’s go plant a tree.”

Story by:

Lonelle Selbo

Photography by:

Deborah Samuel