As incredible as it sounds, two brothers raised on a farm near Port Hope grew up to be big influencers in the government of the Kingdom of Hawaii.

In an era when local farm boys invariably grew up to be local farmers, the story of the Ashford brothers is beyond the pale. Grandsons of one of the first settlers in Port Hope, they were raised on the family farm just east of town; but despite being heirs to one of the best acreages in the township, Volney (born 1844) and Clarence (born 1857) would never have been satisfied with life behind the plough. They left home looking for adventure and academia, and they found it. Both earned university degrees and ended up far from an Ontario winter, in tropical Hawaii of all places, travelling in elite social and government circles. The Ashfords were even embroiled in a political revolution there in the 1890s and were exiled in the aftermath.

Meanwhile, their contemporaries back in Hope Township led their ordinary lives, planting wheat and milking cows. Guess who had more fun.

Volney studied in New York and joined the Union army during the American Civil War. Younger brother Clarence studied law, graduating from the University of Michigan in 1880. It was at the suggestion of his wealthy American cousin, S. G. Wilder, who made a fortune in shipping and sugar and sat in the Hawaiian legislature, that Clarence made the move to Hawaii. It wasn’t long until the boy from Port Hope was noticed by the Hawaiian king.

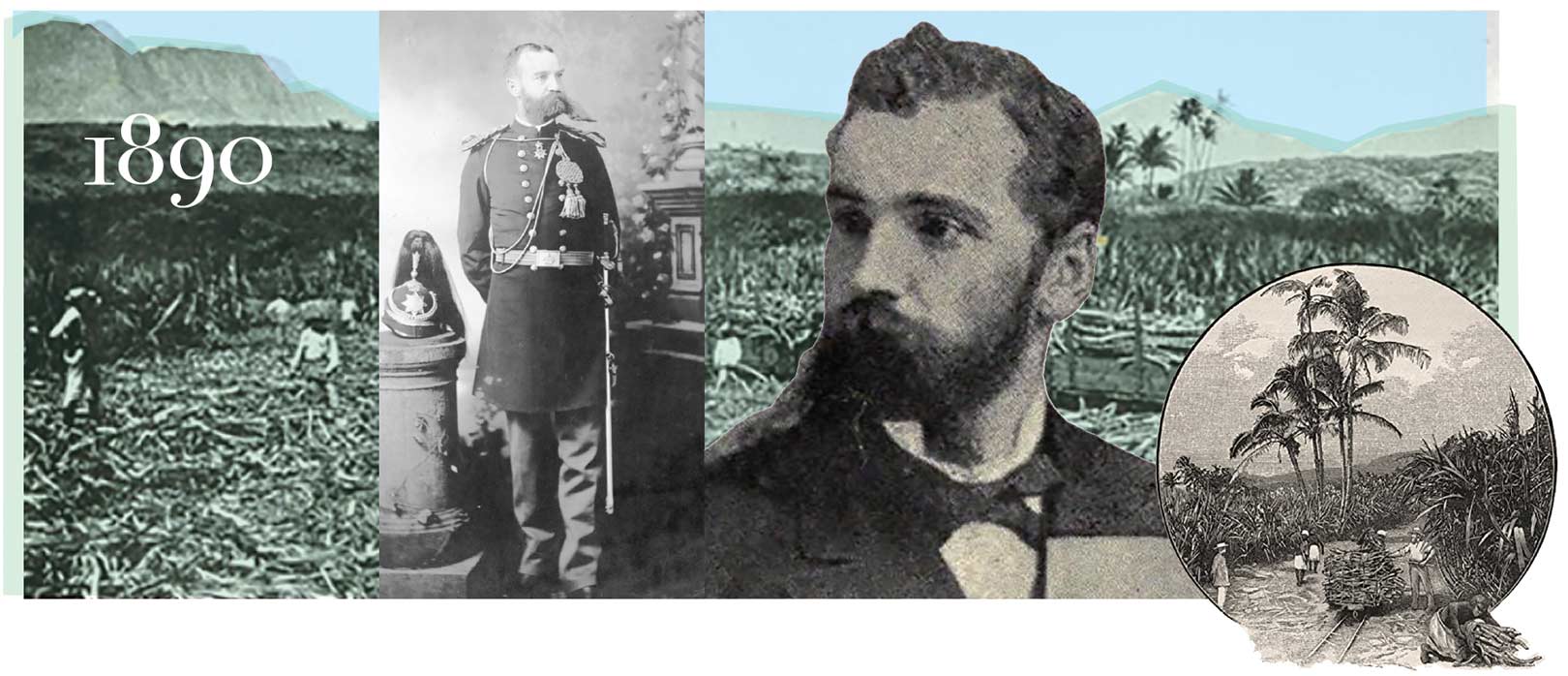

In less than a century, Hawaii had gone from a Polynesian backwater to a hugely successful agricultural- export economy teeming with colonists. The islands weren’t even on the worldwide radar until the late 1700s, when they were visited by the renowned English explorer Captain James Cook, who left such a bad impression that the native islanders eventually murdered him. Aware that the arrival of newcomers was a game-changer, the Indigenous Hawaiians united under a king. From then on, the story of Hawaii was the story of the struggle to hang onto its lands and customs amid a deluge of settlers – first the English, then the Americans, all eager for their share of the booming sugar cane economy (pineapples came later). Just as in North America, the Indigenous population was decimated by European diseases; but unlike here, the Hawaiian monarchs maintained autonomy over their lands, at least for a while.

With every new wave of colonists, the king faced added pressure to democratize land ownership and introduce American-style government. By the 1880s, King Kalakaua no longer ruled absolutely, but shared power with an elected legislature, most of whom were American sugar planters. Most significantly, he was advised by a hand-picked cabinet, of whom the majority were, again, kama‘aina (non-native Hawaiians).

It was at this point that Clarence and Volney Ashford entered the picture. On Wilder’s advice, Kalakaua appointed Clarence to his cabinet in 1887, where he served as attorney general for the kingdom. Meanwhile, Volney had returned from the Civil War to Port Hope and was working as a surveyor on the Midland Railway. Perhaps sensing that his military experience might come in handy, Clarence recruited him to Hawaii. There, Volney made his mark, transforming the local militia – the Honolulu Rifles – into a legitimate paramilitary battalion.

The kingdom needed a military in the wake of constitutional crises and civil unrest through the rest of the 19th century. Outright rebellion against the monarchy broke out in 1887 only to inspire a counter-rebellion in favour of it. But the writing was on the wall. The final insurgency came in 1893 when the last monarch, Queen Lili‘uokalani, was overthrown. A provisional government was established and Hawaii was made an official territory of the United States.

As royalists, the Ashford brothers were jailed in the melee and eventually banished from the islands. Volney settled in San Francisco; he died in 1905 at age 53. For a while Clarence bided his time in Port Hope, where his mother petitioned the prime minister in Ottawa to ensure his safety. When the dust settled, he returned to Hawaii (apparently with no hard feelings) and was appointed a judge in district court. He took his parents with him, selling the homestead in Port Hope (over which the 401 now runs). Clarence died in Honolulu in 1921, age 64. His daughter, Marguerite Kamehaokalani Ashford, became Hawaii’s first female lawyer.

Story by:

Tom Cruickshank