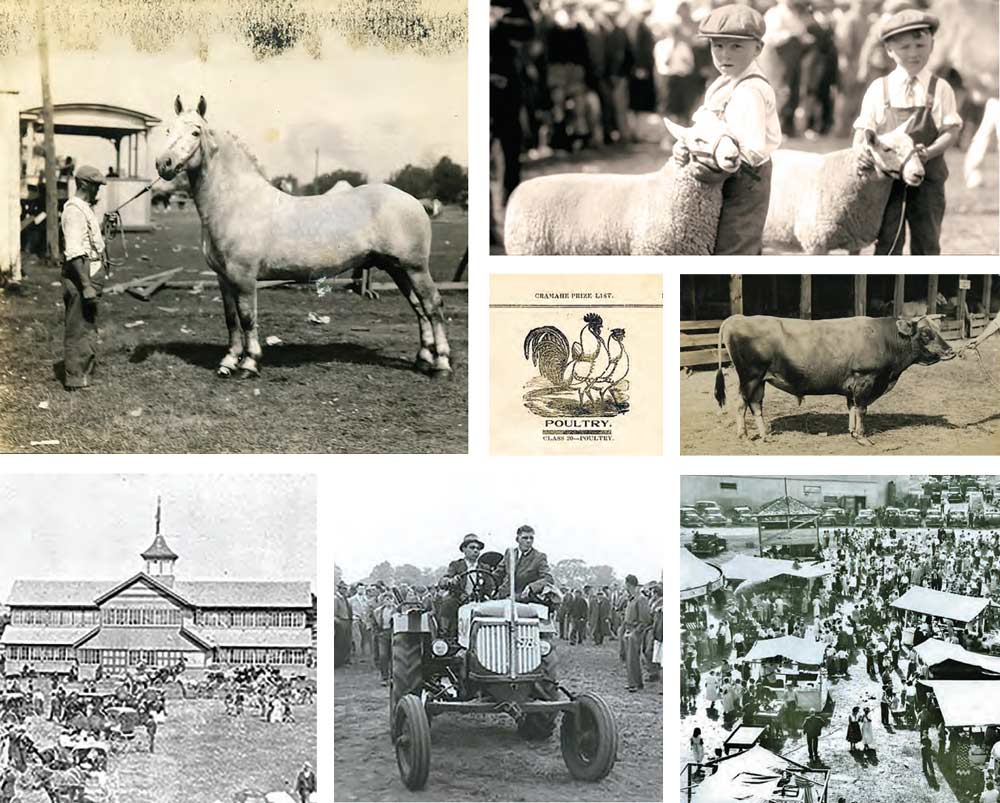

A farmer’s understanding of the characteristics that strengthened a breed of livestock could lead to the coveted Best in Show ribbon.

Agricultural fairs are part of our rural heritage. And like everyone else they’re adapting to changing times and conditions.

When it comes to fall fairs, we live in blue ribbon country. Our local fairs have produced more than their fair share of national livestock champions and record-holding produce, and we are home to some of the oldest fairgrounds in Canada. In past years an estimated one million people have crowded into the region during the fall months to visit fairgrounds with attractions such as Picton’s Crystal Palace (the only one of its kind left in North America) and Roseneath’s 114-year-old carousel.

As with many other events this year, fall fairs are also facing the tough decision of whether or not to fold up their tents, at least until next year. Unlike some other events, however, fairs had to adapt and reinvent themselves long before COVID-19.

We have long cherished country fairs as a vibrant part of our agrarian history, where once a year the farming community comes together to showcase their best livestock, produce and homesteading prowess. Some even equate the fall fair to the Academy Awards of farming!

Fairs, however, were not always farming focused; they started out with a very different purpose.

Fairs in medieval Europe were primarily social and cultural gatherings that featured music and live performances. Because these events coincided with religious holidays, historians speculate that the name “fair” probably originated from feria, the Latin word for a free day. These were days to celebrate and unwind after a hard summer of work.

Merchants and foreign traders seized the marketing opportunities at the events and began organizing booths to sell commodities of every kind, and soon the focus shifted towards commerce and industry. The smaller fairs suffered and started to disappear as merchants favoured larger urban centres where they could sell to more people.

Small fairs were thrown a lifeline in the late 1700s when the British government realized they needed to increase food production. At the behest of King George III, the government decided to subsidize agricultural societies, and in turn the societies began to standardize farming practices throughout Britain and the colonies. These societies took over the running of fall fairs and established them as the agrarian gathering of the year. Eventually the events became regularly scheduled features of rural life in North America.

Over the next hundred years, fall fairs began to resemble those we see today. The latest innovations in seed and equipment populated the booths, livestock competitions were held, and every agricultural society started offering prizes for everything from Best Heifer Calf and Best Bantam Hen to Best McIntosh Apples and Best Woollen Mitts.

The winners were awarded not only bragging rights, but often big cash prizes. At the 1913 Belleville Fair for instance, crochet work in wool, pencil drawings, landscape photos and the best loaf of bread would garner 50 cents for the top prize. The big money – prizes of up to $10 – went to the best stallions, in categories that included Best Carriage Horse and Best Agricultural Horse.

Ploughing, wheat threshing and hay-bale stacking competitions, and even tug-of-war tournaments grew bigger every year and have remained a mainstay at local fairs such as the Port Hope, Campbellford and Roseneath Fairs.

Once a year the farming community showcases their best livestock, produce and homesteading prowess. Some even equate the fall fair to the Academy Awards of farming.

The Marmora and Belleville Fairs built a track and added horse racing to their scheduled events in the early 1900s with the winners taking home up to $50 for first place.

The agricultural boards and societies had succeeded in meeting the needs of their rural communities, and the fall fairs were a snapshot of their innovations. Tractor pulls joined the horse-pulling competitions, and fruits and vegetables showcased their bountiful harvests. In fact, their promotion of agrarian life worked so well that fairs began attracting more urban visitors. To cater to these city folks, many fairs introduced entertainment like Ferris wheels, carousels, mechanized swings, games of chance, live theatre and magicians. The fairs were adapting again.

When the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) was established in 1867 in Toronto, it attracted many of the farming “stars” away from the local fairs, so the agricultural societies scrambled to add new events that celebrated their own specialties in an attempt to distinguish themselves from the CNE.

Even the fall fair mainstay – the parade – adapted itself too. The Picton Fair no longer featured classes of school children at the start of their parade, but celebrated its local sports heroes, while Brighton’s crowds now cheered on a massive tower of apples to mark another successful Applefest.

Fairs continued to grow and thrive even in wartime, although during World War II the CNE’s fairgrounds were transformed into a military training centre, temporarily shuttering the event.

During the war years, local fairs were asked to play an educational role. Victory Garden campaigns encouraged people to grow fruits and vegetables. Displays and advertisements urged fairgoers to work at local orchards and farms to help supply food for the troops overseas. Fair exhibitors offered tips on canning and preserving foods and tips on how to ration supplies.

In the postwar era, fall fairs continued to draw crowds, not only farmers looking to advance and standardize their practices but also visitors from the city, curious about food production and interested in farming. During this time the administration of fall fairs shifted into the hands of volunteer boards and has remained so to this day.

The Ontario Association of Agricultural Societies (OAAS), based in Stirling, now represents more than 200 agricultural societies across the province whose mandate includes the running of annual fall fairs. The OAAS estimates that volunteers contributed 1.4 million hours to Ontario agricultural societies in 2019 alone.

In a recent interview Vince Brennan, the OAAS’s manager, acknowledged the vital role of volunteers.

“Volunteers are the backbone of agricultural fairs,” he says, “and our biggest challenge has been trying to get the younger generation involved.” If there is a bright side to the pandemic, Brennan thinks it’s a renewed interest in farming and traditional homesteading activities.

“I see younger people posting about urban farming and gardening, quilt making and baking. This trend could possibly generate a new group of volunteers,” he comments.

This past August the provincial government chipped in $1 million to help fairs recover after COVID-19, but it will be the enthusiasm of the volunteers that will determine which fairs survive.

“I’m hopeful that we’ll come back bigger and better,” adds Brennan.

In the meantime, fairs such as Campbellford’s are already reimagining themselves online, with events like a sidewalk chalk contest, a virtual talent show, a “big and tall” tomato and zucchini competition, a scarecrow contest and a driving tour.

The Port Hope Fair may still host their popular demolition derby along with other online events, and the Norwood Fair has not yet announced whether it will still hold its popular lawnmower racing event (with proper distancing protocols). Whatever happens this year, fall fairs have provided us with an important lesson in adaptability.

Over the centuries, agricultural fairs have reinvented themselves to respond to changing times. With each new iteration, fairs continue to be an important celebration of everything local, of our collective agrarian history. They remain a cherished annual tradition that we hope to take part in next year and for many years to come.

Story by:

Micol Marotti