Two young farmers pit themselves against the elements in a bid to run a successful sheep farm on an island in Lake Ontario.

BACK IN THE 1980S, MATT FLEGUEL’S PARENTS came across an ad in a local newspaper: A farmer had sheep for sale on Waupoos Island. Matt’s mom, who comes from three generations of sheep farmers in New Zealand, was interested. Before they knew it, the couple had packed up their house in Toronto and moved to Waupoos Island where they started a family and a sheep farm.

Waupoos – a name derived from the Ojibwe word waabooz meaning rabbit – was originally inhabited by the Tyendinaga Mohawk. Today, Waupoos, the area located on Smith Bay on the north shore of Lake Ontario in Prince Edward County, is known for its cold-climate wines, artisan cheeses, apple ciders, fine mustard and highbush blueberries. And you’ll probably see more sheep than rabbits if you visit Waupoos Island.

Matt went off to Queen’s to pursue a degree in engineering – a far cry from sheep farming – but it did not take long for him to realize he was a farmer at heart. “I’d rather spend a long day on a farm than an hour sitting in traffic on the DVP!” Matt laughs. In 2016, Matt and his wife Liz took over the Fleguel family farm and established Waupoos Island Sheep. The farm has grown from the few hundred sheep Matt’s parents started with, to over 1,900 head today.

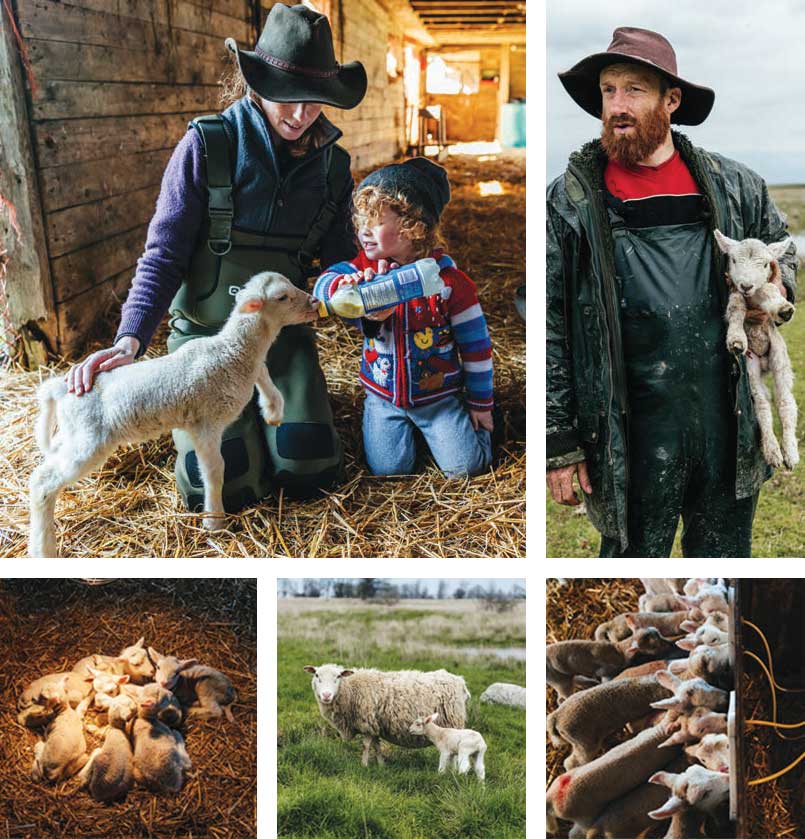

Lambing season can be joyous, but it is also the most hectic and stressful time of the year for sheep farmers – it certainly is for Matt and Liz. Imagine the logistical challenge of ferrying 1,900 ewes from the mainland over the water to Waupoos Island, and then monitoring the well-being of over 2,000 freshly born lambs and their mothers. The flock is always at the mercy of the unpredictable mood of Canadian spring. Then there is the threat of the coyotes – the natural predators that prowl the fields – which explains why there are six loyal and immensely powerful Great Pyrenees that watch and protect the flock.

Life on a sheep farm isn’t as fluffy and cute as you might imagine. In fact, it is often grim. “If you have livestock, you will have dead stock; that’s just how it is,” says Matt as he picks up a few dead lambs from the field. “We lost 60 lambs yesterday, mostly to dystocia and hypothermia…the most we’ve ever lost in 24 hours.” The weather is hugely important for the survival of newborn lambs. With a very cold and wet spring like the one we just experienced, so much life is at stake. “Mother nature pretty much does most of the work during lambing season. Our job is to make sure we help these lambs stay alive and healthy.” Matt continues, “Sometimes we do have to interfere when a ewe is having a hard time giving birth…like that one on her back over there!” Matt leaps off the ATV before he finishes the sentence and gets a hold of the exhausted ewe. The ewe, moaning and bleating on the ground, is obviously in distress; only the tip of the nose and the front feet of the lamb can be seen emerging from the ewe, seemingly stuck. Matt grabs onto the front legs of the lamb, which is covered in a yellowish amniotic fluid and tries to gently pull the baby out, all the while explaining what is going on. “He’s a big boy, look at him! Which explains why the ewe is having such a hard time,” says Matt as he successfully assists the birth of a healthy lamb.

Most ewes give birth to just one lamb, although some will have twins, and some ewes will even have triplets. In the case of multiple births, often a ewe’s natural instinct will tell her to abandon one or two lambs to ensure the survival of another. That’s when Matt and Liz step in. In lambing season, Matt and Liz scour the fields looking for abandoned lambs that will be taken back to the barn where heat lamps and a milk machine are set up to keep them warm and fed around the clock. “Our daughter, Thora, does a good job keeping the orphaned lambs company in the barn – running and playing with them – she even sings to the lambs sometimes!” says Liz with a smile. “Matt was probably Thora’s age when he first held a lamb.”

Matt and Liz are carrying on an agricultural tradition that dates back to the mid-1600s when sheep were brought over to Quebec from France. In those early days, sheep were needed for manufacturing clothing and to feed the settlers. Nowadays, wool has very little commercial value for Canadian breeders. Lamb meat has become the main product for the farmer.

Matt and Liz sell most of their lambs to the GTA, where the demand is high and they can get top dollar for their grass-finished lambs. “The way we keep our sheep is very much in line with the traditional New Zealand-style; we don’t keep the sheep indoors,” says Matt. “We also don’t feed our lambs any grain – just grass – which results in much better quality and better tasting meat. By keeping the ewes outdoors year-round and moving them from pasture to pasture, they stay healthier and develop fuller and thicker fleece.” says Liz, who studied biology and is now teaching a pre-health program part-time at St. Lawrence College. “We are running one of the largest pasture-based operations in Ontario.”

The community plays an important role in this style of sheep farming. So much land is required to successfully run a pasture-based sheep farm like the Waupoos Island Sheep operation. “We get a lot of passionate volunteers who are happy to help, and a lot of curious spectators snapping photos as we move our sheep from one pasture to another in the County,” Matt says. “People here have been very kind and supportive of us – the stories and photos they’ve been sharing on social media has helped raise awareness about what we do and how we do it. It is very important to have a good relationship with our community because we depend on them for access to pasture and roads we don’t otherwise own.”

Things have changed a lot since the first farmers put down roots in Prince Edward County, but the interdependent relationship between the farm community and local residents has remained the same. The gruelling hard work and the seemingly idyllic life of sheep farmers could be easily overlooked and romanticized, but somehow Matt and Liz handle the long hours and sleepless nights in stride. “Animal welfare is our top priority at the farm; it brings us so much pride and joy to see our sheep healthy. They all live a good life roaming free in this little slice of paradise that is Prince Edward County,” Liz says, as she hands a bottle of milk to Thora and shows her how to feed a little lamb in the warmth of the heat lamps in their century old barn.

Story by:

Johnny C. Y. Lam

Photography by:

Johnny C. Y. Lam