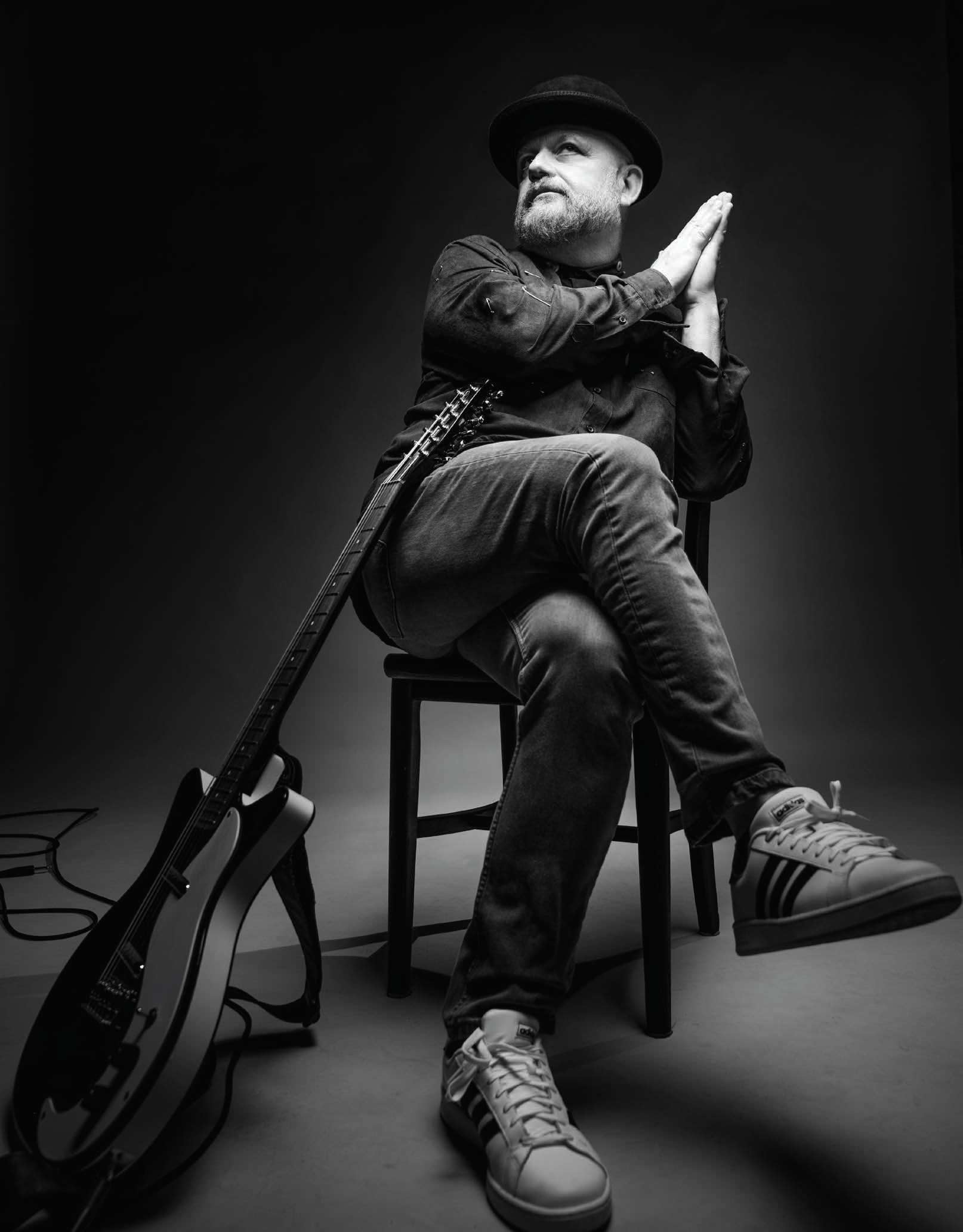

Architect Dimitri Papatheodorou thrives on a foundation of creativity.

Many people associate moving to the country with a kind of rebirth – a reawakening of the senses if you will. But for Dimitri Papatheodorou, a true modern Renaissance man, moving to the country nine years ago also brought a greater sense of self and purpose. As an architect, teacher, visual artist and musician, Dimitri is living his best life in a beautifully restored 1861 stone house just outside of Warkworth, with his partner of 22 years, Ottawa-born medical doctor Jamie Read, who serendipitously found the home online in 2012. It was initially Jamie’s vision to escape to the country from their urban Toronto digs, but once the two moved into their six-acre property in 2013, Dimitri never looked back.

And as the decades progressed, life has just gotten sweeter for them both. “I feel like I’m coming out a second time,” says the 57-year-old Dimitri. “I came out as a gay man, but I was always very introverted in Toronto, because it’s such a big place and everybody is anonymous. But when you come into the country, you can’t be anonymous. Like you can’t not say hello to people. And I just feel like I’m a somebody,” he laughs. “I know it sounds so corny, but it’s true… In Toronto I was a nobody and here I’m somebody.”

Growing up in Toronto’s Greek village and later, in suburban Don Mills, Dimitri was the son of immigrant parents who came to Canada from their beloved Greece in 1958, in search of a better life. Like most uneducated immigrants, it was their nose-to-the- grindstone work ethic that saw them through. “My dad was a dishwasher at the time, because they came to Canada without English,” Dimitri explains. “My dad ended up working in kitchens and my mum worked in a factory making high end sheepskin coats for Holt Renfrew. And she worked until she was 72…” But again, like most immigrants, Dimitri’s parents were determined to support their son’s dreams. And with the sharp focus that he displayed, that wasn’t hard to do. Dimitri claims he decided he wanted to be an architect when he was only seven years old. “I started drawing up dream homes for my family, and I also drew fancy sports cars,” he recollects. “Every boy likes to do those things, but every gay boy I guess, is attracted more to more essential arts. And the reason why I ended up in architecture is because of painting and drawing.”

Dimitri’s parents were fiercely proud of their son’s burgeoning talents. “My parents would entertain a lot because my dad was in hospitality. And they would say, ‘Bring your drawings to show our guests.’ And then they’d say, ‘You know you have to give this as a gift to them because they’re going back to Greece.’ So they taught me how to give as well. And to this day, I have a lot of difficulty taking money for work,” he says with a laugh.

Dimitri’s entry into the profession came early. Right after his first year at the University of Waterloo, when he was only 18, he started working in the field, eventually establishing himself as a successful architect. He soon had an impressive array of social housing and modern residential projects to his credit, including designing a country house for one of his rock idols, Alex Lifeson of famed Canadian heavy metal band, Rush. When he was 40, Dimitri struck out on his own, and he also began teaching architectural design at Ryerson University – a part-time gig he continues to this day, and one that he sees as a true blessing. “I get so much from these young kids,” he reflects. “It keeps my brain going. It keeps me current.” Never one to sit still, Dimitri’s passion for painting also continued throughout the years, and in 2002 he had his first show. Though he never went to art school, he feels his architecture studies were very much related, and his paintings are indeed very architectural in nature, exploring notions of space and light.

“And it’s beautifully quiet, there are no sirens or horns. You hear coyotes and you hear animals… And the light is different…”

THE PERIPHERY

One of Dimitri’s greatest joys these days is the gallery he recently created in one of the property’s outbuildings. The Periphery is housed in what used to be Dimitri’s own studio space, which the architect describes as essentially the size of a one-bedroom condo in downtown Toronto. In fact, it was being able to occupy this spacious studio that helped sell Dimitri on the house in the first place. Now, turning the space into a kind of rural studio – not a commercial one, but one that he can share with other artists in the area and his own students – is a way of giving back to the artist community that Warkworth is famous for. Dimitri credits COVID as the catalyst that made him want to turn his studio into a gallery, realizing that as he gets older, he wants to work more at home. “You can consult, and it’s easy to be an architect and only visit the site occasionally,” he rationalizes. He also knew that having a full-blown gallery would fit perfectly with his education ideals. “This is partly what I teach as well: issues of dwelling and home, and our relationship with the land,” he explains. “I started thinking, “How do I dwell in this space, while honouring history, which includes First Nations and settler history? I’m not a farmer. I can’t fake being a farmer. I make art and I make design things. So being here and working and now bringing the architecture students out here for the past two years has been wonderful.” Dimitri also insists that the Periphery is not just about fine art. It’s about living closer to the land, and a switch from merely thinking about real estate as purely part of one’s investment portfolio. “This is home, this is where we live,” he stresses. “Yeah, it’s a retirement savings I guess, but the idea of trying to live as much as possible in the moment is also connected to living closer to the land and doing art not just inside the Periphery, but outside as well, like creating installations.”

It’s also about inviting others to participate, like well-known local textile artist Dorothy Caldwell, who showed at the gallery last fall. “It’s purely a private space for us to take risks, to do things and say, ‘Well, let’s test it and see if this works.’ Dimitri is also working with Northumberland County’s Westben Centre for Connection and Creativity through Music. He designed their outdoor amphitheatre, Willow Hill, last year and is talking with them about how they could be more visually focused. Of course Dimitri’s musical pursuits – and he’s been playing music since junior high – are also part of his personal picture, and hopefully the Periphery will host musicians in the future. It’s yet another passion in Dimitri’s prolific prism: His band, “The John Cleats,” which he formed in 2017, has recorded five albums, with a sixth on its way.

With such a robust creative life, it’s hard to imagine that Dimitri has time for much else. But his social life with Jamie, who works as Medical Director of the Trent Hills Family Health Team in nearby Campbellford, is very active. “We’ve made more friends here than in Toronto. Honestly, we didn’t know our neighbours as well in Toronto, which is typical,” says Dimitri. “Here, our neighbours rescue us when we get stuck in the snow, and they’re just so kind.” And if human kindness, friendship, creative inspiration, and gorgeous surroundings aren’t enough, country living for Dimitri has yet another added value. “It causes you to have more time to reflect. And it’s beautifully quiet,” he muses. “There are no sirens or horns. You hear coyotes and you hear animals… And the light is different… the moonlight. And oh, my God, the stars! I mean, it does make sense as you get older, right?”

As for the glorious landscape of Northumberland County itself, Dimitri says it reminds him of his ancestral homeland, Arcadia, in central Greece. “Each of us re-creates ‘home’ in whatever fashion we remember it, to help us feel safe and secure,” he opines. “For me, there’s a connection between Northumberland County with its rolling hills and pastoral, bucolic feel and the melancholic mountains of Arcadia, which look more like rolling hills than actual mountains due to their geological age.” And ultimately, if it’s all about finding home for this architect, then evidently he’s found it… and then some.

Story by:

Jeanne Beker

Photography by:

Rawle Johnson, Bigredtruck