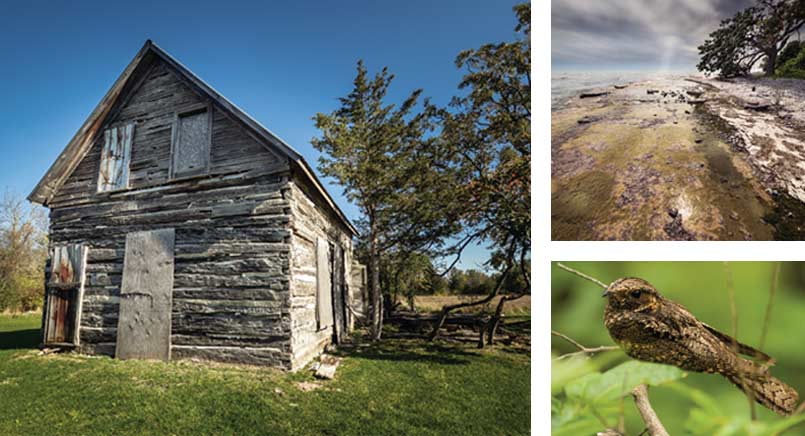

Clockwise: log house on the Hudgin Rose Nature Reserve; South Shore at Prince Edward Point; eastern whip-poor-will

Resources, knowledge, ideas and efforts are coming together to protect the ecological treasures of the County’s south shore.

Prince Edward County’s south shore can seem a windswept, lonely, even bleak landscape where grey waves break on cobbled beaches and a thin layer of soil struggles to support shrubs and stunted trees. Looks can be deceiving. The south shore is one of the County’s great ecological treasures, a home to rare plants and animals, a refuge for migrating birds and even a location for a celebrated chapter of Canada’s aviation history.

It’s a treasure the South Shore Joint Initiative (SSJI) has been working hard to preserve. As defined by the SSJI, the south shore begins at Point Petre and stretches east to the Prince Edward Point National Wildlife Area. The boundaries carry around the north side of the point to include the Little Bluff

Conservation Area and end in the Black River area. At 26 kilometres, it is the longest stretch of undeveloped shoreline on the north shore of Lake Ontario, unique and worthy of preservation.

Within its boundaries, biologists know of at least 41 animal and plant species at risk of becoming endangered or threatened. On the list are bald eagles, black terns, grassland birds, four species of warbler, four species of turtle, the monarch butterfly, and the butternut tree. During the winter, the waters of the south shore shelter globally significant flocks of waterfowl, and in the spring, the south shore is an important first resting stop for migrating songbirds that have made their way across Lake Ontario.

The geology of the region is unique. Cheryl Anderson, vice president of the SSJI, explains that the south shore is an alvar, a limestone plain covered with only a thin layer of soil. “It’s a special geology,” she says. “There’s not a lot of that type of landscape.” Aside from the Great Lakes region, alvars are found only in Scandinavia. Because of their thin soils, alvars are subject to a cycle of extreme wet in the cold months followed by drought during the summer.

This results in a niche environment that creates ephemeral ponds in spring and supports rare plants along with grassland bird species such as bobolinks, eastern meadowlarks and grasshopper sparrows.

LEGACIES OF WATCHFULNESS AND PROTECTION

The movement to protect the south shore has its roots in the proposal to build nine industrial turbines on an 800-acre Crown land site at Ostrander Point. Although the project would have provided enough electricity to power 6,000 homes, opponents to the project raised objections based on its potential adverse effects on migrating birds and its impacts on the Blanding’s turtle and the eastern whip-poor-will, both of which are listed as threatened species.

Threatened species won the day. In 2015, the Ontario Court of Appeal ruled in favour of upholding an Environmental Review Tribunal decision that the wind turbine project would cause serious and irreversible harm to the Blanding’s turtle.

Riding on the waves of success, the next mission was to highlight the significance of the south shore. Eight conservation organizations, including the Hastings Prince Edward Land Trust, three area field naturalist groups, Nature Canada, Ontario Nature and the Prince Edward Point Bird Observatory banded together under the umbrella of the SSJI to carry out activities ranging from shore strolls to land acquisition and protection.

Although not a formal partner in the SSJI, the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) has acquired two pieces of south shore property – the Hudgin Rose Nature Reserve and the MapleCross Coastline Reserve on either side of the Ostrander Point lands. The NCC has also provided funding towards the purchase of the 490-acre Miller Family Nature Reserve by the Hastings Prince Edward Land Trust. Another parcel of land on Prince Edward Point is owned and protected by Ducks Unlimited.

By far the biggest holder of undeveloped lands is the Province of Ontario, which owns both Ostrander Point and 3,200 acres at Point Petre. The protection of those properties has been the main focus of the South Shore Joint Initiative. Good news came in the fall of 2020 when the Province announced its intent to designate the two properties as a conservation reserve.

Cheryl Anderson explains that the process of creating the conservation reserve is ongoing. Steps so far have included studies by biologists, provided by the Nature Conservancy of Canada, who “have found fabulous biodiversity.”

When the two properties receive official status as conservation reserves, it will mean that a total of about 6,000 acres, or 40 percent of the south shore, are protected from development.

“You start to see the pieces fitting in,” says Cheryl Anderson.

A TREASURE TROVE FOR HISTORIANS

Naturalists will be celebrating the untouched lands of the south shore, but history buffs will also find the area interesting. Although signs of human impact are minimal through much of the area, its history of European settlement goes back two centuries.

One project historians will appreciate is the restoration of the log house on the Hudgin Rose Nature Reserve. The Nature Conservancy of Canada owns the land but doesn’t get involved in preserving heritage architecture, so a subcommittee of the SSJI has taken the project on. The house, which was designated under the Ontario Heritage Act in 2011, dates back to 1865. The home was first occupied by the Hudgin family –Moses, a fisherman and subsistence farmer, and his wife Anne, and their nine children. It would eventually house three generations of Hudgins. The goal of the SSJI is to use the house as a small museum or a base for nature studies.

JETS THAT RAN RINGS AROUND THE COMPETITION

The Ostrander Point and Point Petre properties have more recent histories of interest, dating back to Cold War times, when they were used for military purposes, including training and testing. The Department of National Defence continues to maintain an antenna site on a parcel of land at Point Petre.

If you look up satellite imagery for Point Petre and examine the area north of the lighthouse, just inland from the western shore of the point, you’ll find a puzzling man-made feature, a perfectly round asphalt track in the scrub, which some local historians have christened “the Orenda Ring.” The ring was built to test the Orenda jet engine, which was the world’s most powerful jet engine designed and built by Canadians in the late 40s and early 50s. Although it sounds risky, the testing procedure was simple. The engine was attached to a cart tethered by chain to an iron post at the centre of the circular track. Testing involved firing the engine and observing as it and the cart spun around the track.

Orenda produced engines for the Avro CF-100 Canuck, the Canadair F-86 Sabre fighter jet, and also built a prototype engine for the legendary Avro Arrow. Point Petre’s connection to the Arrow includes its use as a launching site for scale models of the craft that were tested over Lake Ontario. In 2018, divers searching off Point Petre recovered a one-eighth scale model of the plane, which they believe was used to test its then-revolutionary deltawing design.

CREATING CONTINUITY

SSJI representatives are confident that the province will formalize the conservation reserve status for the Ostrander and Point Petre properties, which would be followed by the creation of a management plan for the properties, administered by Sandbanks Provincial Park.

While Sandbanks experiences heavy vacation use in the summer season, SSJI president John Hirsch envisions a different scenario for the two south shore properties, which are unlikely to allow camping, charge admission, or have paved parking lots. “We want to discourage over-tourism,” he says. “We want people to appreciate the reserve.”

Looking ahead, the goal of the SSJI is to protect the natural heritage of privately owned lands as well as the already preserved lands on the south shore. John Hirsch explains that during Prince Edward County’s recent creation of a new official plan, the SSJI played a big role in making sure the entire south shore was zoned as a natural core area, a designation that sets strict limits on residential development and lot severances.

The south shore, says Hirsch, is currently a patchwork of protected lands. “We want to turn that patchwork into a full quilt.”

At 26 kilometres, this section of land is the longest stretch of undeveloped shoreline on the north shore of Lake Ontario

In the spring, the south shore is an important first resting stop for migrating songbirds that have made the long flight across Lake Ontario.

Story by:

Norm Wagenaar