With a sea of prairie flowers brushing our legs as we walk through it, one of Canada’s rare long-grass prairies is once again thriving.

When we think of how Northumberland appeared to European settlers arriving in the early 1800s, we might imagine a landscape dominated by tall forests of hardwoods and white pine. The reality was something quite different. The northern reaches of the county, extending to the shores of Rice Lake, included more than 40,000 hectares of tall grass prairie, an ecosystem that included globally rare black oak savanna and oak woodlands.

North America’s tall grass prairie once began on the Great Plains, and in places where local soils, microclimate and fire conditions favour grasslands over forest, it spread into Southern and Central Ontario as far east as the Rice Lake plains.

Those sandy plains featured a mix of drought-tolerant grasses, wildflowers, black oak and other oaks in a rolling open landscape. It was an ecosystem that depended on periodic fires, started by either lightning strikes or the Mississauga Anishinaabeg and Haudenosaunee, who sought to keep the lands clear of encroaching forest. The prairie grassland provided plants for food and medicine and supported wildlife habitat. The association of tall grass prairie and fire led to the Anishinhaabe name for the area: Pemedashkotayang – Lake of the Burning Plains.

European settlers found the open lands of the Rice Lake Plains easy to farm and ploughed the prairie under, with the result that tall grass prairie is rare today, both locally and globally. Across Ontario only about two percent of the original tall grass prairie remains in scattered locations. One of these remaining patches is right in our backyard, at the Hazel Bird Nature Reserve, located just south of Rice Lake near the intersection of Oak Ridges Drive and Harwood Road.

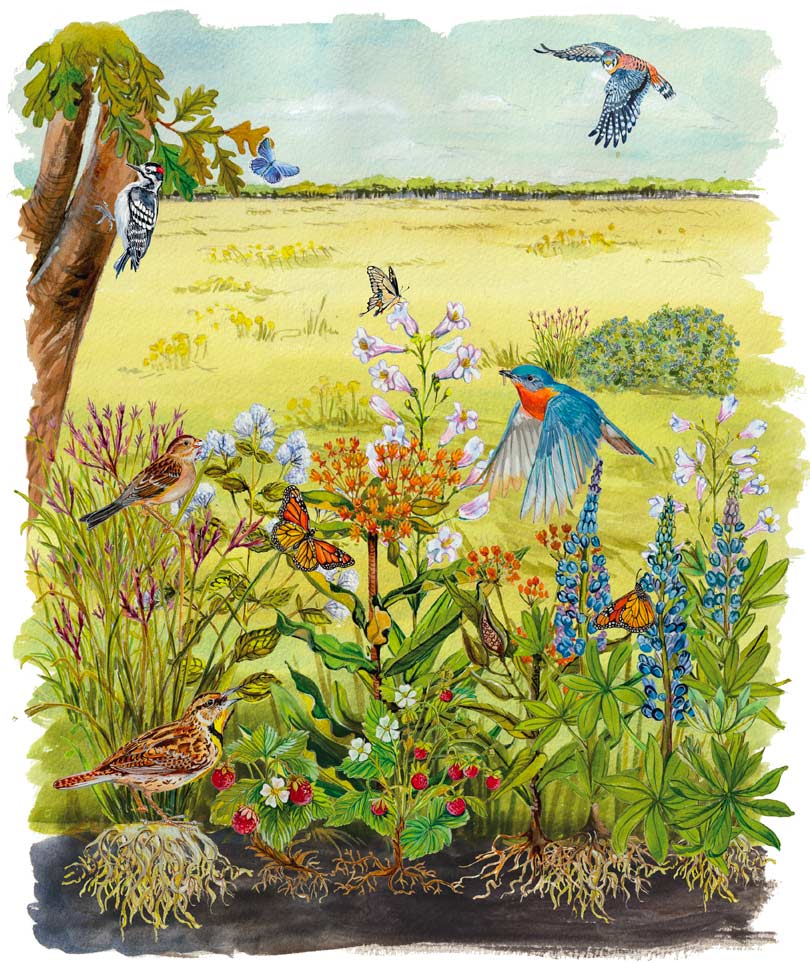

The reserve, which features 3.6 kilometres of trail, is a great spot for a walk. In winter, bring your cross country skis or snowshoes, and in spring, watch for emerging flowers such as prairie buttercup. In midsummer, bring your binoculars to view grassland birds such as Eastern meadowlarks and grasshopper and field sparrows. You can also see bluebirds, ravens, many species of woodpeckers, and raptors such as kestrels and northern harriers. The grasslands provide habitat for butterflies including monarchs, giant swallowtails and eastern-tailed blues.

Many of the plant species that distinguish tall grass communities come into full view in late summer and early fall. These include tall swaying rust-coloured big bluestem grass, with its distinctive “turkey foot” seedheads, butterfly milkweed, New Jersey tea and the colourfully named hairy beardtongue. The long list of native plants on the property includes blueberries, blue lupine, strawberries, majestic white and black oak trees and white pine.

The initial 116-hectare tract of the Hazel Bird Nature Reserve was purchased by the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) in 2011. It is named in honour of Hazel Bird, a local teacher and naturalist, who undertook a huge conservation effort to support Eastern bluebird populations by putting up more than 400 bluebird boxes and maintaining them for nearly 40 years. As the Eastern bluebird populations recovered and the species was no longer under threat, the boxes were gradually removed. The NCC has reinstalled some, which are once again in use.

Just this year, the size of the Hazel Bird Nature Reserve was increased by one-third with the donation of 40 hectares of neighbouring land by Cobourg resident John O’Neill. He and his partner, Colin Jones, bought the land in 1996 as a rural getaway. At the time they didn’t understand its full ecological value. However, “After talking with local and provincial naturalists, we came to appreciate that the ecosystem on our land was very special and also very rare in Southern Ontario,” says O’Neill. “We agreed that we should somehow find a way to preserve it and protect it from development. When the Hazel Bird Nature Reserve was created on our southern border, we were delighted, and the idea of donating the land to the NCC was born.”

Restoring and maintaining a tall grass prairie requires careful planning and lots of labour, which is provided by a mix of NCC staff and volunteers. The NCC website lists regularly scheduled volunteer events, which present a great opportunity to learn about natural history while doing important work such as removing invasive plants that discourage the growth of native prairie species. At Hazel Bird these species include dog-strangling vine and Scotch pine.

Fire continues to be an important tool to maintain the prairie. Val Deziel, the NCC’s Co-ordinator of Conservation Biology for the Rice Lake Plains, says burns are typically done annually through dif ferent sections of the property, a restoration practice inspired by the burning done at the nearby Alderville First Nation Black Oak Savanna. Prescribed burns are carefully controlled by an expert team of forestry professionals and former firefighters. The fire removes the dead plant material that accumulates quickly on the prairie, transforming it into ash and making its nutrients available to plants. Sunlight warms the blackened ground, stimulating the dormant roots and restoring the prairie grasses and wildflowers.

Tall grass prairie provides us with a living link to our area’s natural history and may play a role in a sustainable future. The flowers of tall grass prairies support insect species, including native pollinators, which are declining in number due in part to habitat loss and pesticide use. The deep roots of the plants, evolved to survive periods of drought, can extend to a depth of three metres and help control erosion. The lush ecosystem of this vegetation soaks up and stores up to 1.7 tonnes of carbon per acre per year, representing a potentially important resource as the world grapples with climate change. “This storage ability is cumulative over time so prairie soil is able to sequester or store large volumes of carbon in a natural, safe, effective and reliable way compared to the risky and expensive practice of pumping CO2 underground,” states the Tallgrass Ontario website.

Tall grass prairie on the Rice Lake Plains is a local wonder. Visit this summer and enjoy a “sea of prairie flowers” cultivated by fire, a host of butterflies aloft on the breeze, and a chorus of songbirds in the whispering grasslands.

The Nature Conservancy of Canada encourages visitors to explore the Hazel Bird Nature Reserve. The walking trail is accessible from a parking lot on Beaver Meadow Road East, just west of Johnstone Road North.

Watershed readers interested in volunteering at the Hazel Bird site and other NCC properties can check for opportunities online at https://www.natureconservancy. ca/en/what-you-can-do/conservation-volunteers/ events

Tall grass prairie provides us with a living link to our area’s natural history and may play a role in a sustainable future.

Story by:

Norm Wagenaar

Illustration by:

Thérèse Cilia