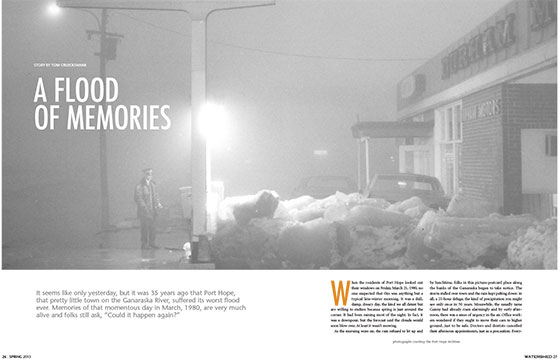

It seems like only yesterday, but it was 35 years ago that Port Hope, that pretty little town on the Ganaraska River, suffered its worst flood ever. Memories of that momentous day in March, 1980, are very much alive and folks still ask, “Could it happen again?”

When the residents of Port Hope looked out their windows on Friday,March 21, 1980, no one suspected that this was anything but a typical late-winter morning. It was a dull, damp, dreary day, the kind we all detest but are willing to endure because spring is just around the corner. It had been raining most of the night. In fact, it was a downpour, but the forecast said the clouds would soon blow over. At least it wasn’t snowing.

As the morning wore on, the rain refused to let up and by lunchtime, folks in this picture-postcard place along the banks of the Ganaraska began to take notice. The storm stalled over town and the rain kept pelting down: in all, a 21-hour deluge, the kind of precipitation you might see only once in 50 years. Meanwhile, the usually tame Ganny had already risen alarmingly and by early afternoon, there was a sense of urgency in the air. Office workers wondered if they ought to move their cars to higher ground, just to be safe. Doctors and dentists cancelled their afternoon appointments, just as a precaution. Everyone knew that downtown Port Hope was built on low-lying land and was highly vulnerable to floods. And with the ground still frozen after a long winter, none of the rain on March 21 had a chance to soak into the earth. It had nowhere to go but straight down the Ganaraska valley, right through the middle of town toward Lake Ontario.

It turned out to be the worst flood Port Hope had ever seen. And that’s saying something, because downtown Port Hope is notorious for flooding, with memorable disasters in 1909, 1929, 1936 and 1937, to name a few. But this was in a class by itself. For the duration, the town came to a standstill, the power was out downtown and folks were abuzz with news of the damages wrought and the near misses that could have made things much worse. Even today, 35 years later, memories of this most recent flood are still quite vivid. Indeed, like anyone who can recall the moon landing or the accident that killed Princess Diana, anyone who lived in Port Hope in 1980 remembers where they were on the afternoon and evening of March 21.

Sue Town, born and raised in Port Hope, was newly married and renting a basement apartment in a riverside bungalow in the heart of downtown, just below the Walton Street bridge. “I had walked uptown earlier that day and saw a huge rooster tail swirling in the river,” she recalls. But she had seen the Ganny in flood before and had no inkling that this was any more serious than usual. In fact, most of Port Hope wasn’t worried, having heard news reports that the town had only that morning dynamited an ice jam to clear a path for the annual spring run-off. But only a few hours later, Sue and her husband were scrambling upstairs with her most precious belongings, seeking refuge in their landlord’s main-floor apartment. “We should have left the house completely, because we soon found ourselves trapped with nowhere to go,” she says. “Behind us, the river was a torrent. In front, the floodwater was cutting a new channel down the street and past the house.We were surrounded.”

Meanwhile, Robin Long had come back from a business luncheon in Cobourg to find water lapping against the downtown building that housed his family’s real estate and insurance brokerage business. “I knew this was no ordinary flood as I watched huge blocks of ice float down the street,” he remembers. “They were so big and dangerous that front-end loaders were there to push them out of harm’s way. Imagine the damage if one of them had smashed through a window.”

Kathryn McHolm was taken aback, too. A local artist who had only recently opened an artisan’s shop and gallery, she had seen her share of Port Hope floods, but still: “To see water flowing like a river down Queen Street, right in front of my store, was the most bizarre thing.”

By late afternoon, the rain had finally stopped. A police cruiser patrolled downtown, its loudspeaker advising anyone within earshot to flee to higher ground. But eventually, even it had to turn back as the Ganaraska kept rising, the overflow carving its own impromptu route through and around downtown buildings. Emergency crews piled a bank of sandbags strategically in an effort to redirect the water back to the riverbed. No doubt it did some good, but even so, Kathryn – and every other downtown merchant – scrambled to save her inventory. “It was a mad rush, but we moved everything from the store shelves – paintings, wreaths, baskets, candles, and clothing – to the upstairs workshop,” she recalls. Only a few doors away, Robin remembers, “We moved all our filing cabinets upstairs, dozens of them,” he says. “Remember, this was the pre-computer era and our hard copies were our only records.” It was enough to drain all his energy, but Robin found a moment to peek downstairs into the cellar. “It was knee-deep with water pouring in from a broken storm drain. I rolled up my pantlegs and was going to walk through and plug the leak with a sandbag. But the water was freezing cold and my legs cramped immediately.”

So Robin quickly changed his plan and went back upstairs, where he and his wife and a few friends spent the rest of the night sweeping water out the back door. “What I remember most is the smell,” he recalls. “Wet carpet, wet cardboard, mud and sewage. And especially furnace oil, leaking from overturned fuel tanks. You could smell it all over downtown.”

Meanwhile, every street within a stone’s throw of the river was closed, but it didn’t stop a crowd of onlookers from gathering at a safe vantage point. “Some of them were standing just across the street from our house,” says Sue. “We could see them from the living room window, but we didn’t dare leave to join them because between us and them was a torrent of floodwater.” There was no telling how deep it was; likewise, the current was strong enough that it would have been dangerous to cross. In fact, the flow quickly undermined the roadbed and carried away enormous chunks of asphalt and tons and tons of gravel. Sue’s pickup truck was parked out front, and as the flood wore on, it began to sink as the earth beneath it was swept away. “At one point, we could see a front-end loader coming to rescue us,” Sue continues. “But they gave up because the water in front of the house was just too fast and deep.”

Darkness fell. The power was out. And the worst wasn’t over yet. Over on Ontario Street, the Sears building – only three years-old – was taking the full brunt of the flood and, like the street in front of Sue’s house, its foundation was badly eroded in no time. Then a wall collapsed. Floodwater carried off merchandise. New refrigerators, stoves and furniture were seen bobbing down the river. Helpless against the force of the water, the roof eventually crashed to the ground and the Sears building was a total loss.

Across the street, some of the regulars at the Ganaraska Hotel, a beer parlour on the riverbank, had been imbibing all afternoon without a care, only to sober up fast when it was time to go home. “A number of patrons were too inebriated to heed the warning to leave the building,” the newspaper reported later, recounting how a policeman, secured by a rope, had to help several of them to safety. Navigating the current, one lost his balance and both the hotel patron and the patrolman tumbled to the ground. Each was sent to hospital.

“The water just kept coming,” Sue says, remembering that the dull roar of the rushing water just wouldn’t let up. “Every now and then, there was a horrible scraping sound, which we soon figured was bedrock dislodging from the river bottom.” She watched, awestruck as the current tossed huge slabs of rock toward Lake Ontario. “If nothing else, I learned a new appreciation for the power of water that night.”

Over the millennia, who knows how many times the Ganny has spilled over its banks? Whatever the case, the first recorded flood in Port Hope occurred in 1850, when the river rose ten feet above normal that spring. From then on, townsfolk have kept a close watch, hoping against hope that the inevitable wouldn’t happen again. But of course, it has many times. In 1878, no fewer than 15 dams in the Ganaraska watershed were washed away. In 1890, every bridge in Port Hope was carried off and a child drowned. In 1909, the Evening Guide reported, “The water reached an enormous height and carried everything away in its course,” adding cheekily, “The front of William Smith’s barber shop was taken out and the barber’s chair damaged to some extent – a close shave.”

In 1929, there were two floods, one on January 7 and a second only three weeks later. The 1936 flood, “left in its wake terror and destruction,” only to be topped by a “sweeping rampage” in 1937 in which “the town of Port Hope never saw so much water.” In more recent memory, floods in 1973 and ’74 were recorded. Both of these were caused by ice dams near the river mouth, well downstream from the downtown core, so damage was comparatively minor. Even so, a couple of cars from the nearby auto dealership were washed into Lake Ontario.

When Port Hope was founded at the close of the 18th century, no one had flooding in mind. In fact, despite the steep valley, the virgin site was thought to be the perfect place for a town to grow. Already there was a northbound trail to connect the fledgling village with the interior and with a little work, the swamp at the mouth of the Ganaraska could be dredged into a decent harbour. Most important of all, the river boasted several sites suitable for mill dams, paramount to industrial growth in the age of water power. Indeed, it was only natural that Port Hope would thrive, but like many towns established at the time, its Achilles heel would forever be that its riverside location left it wide open to flooding.

And Port Hope was even more vulnerable than some other places, including arch-rival Cobourg. In fact, the town was cursed by a quirk of geography, namely that just before it empties into Lake Ontario, the Ganaraska takes a sharp right turn and forces itself into a narrow bottleneck. Early in Port Hope’s history, this seemed like the logical spot at which to ford the stream and build the bridge around which the town would grow. But it also set the stage for future floods. “You have to marvel how all the water that drained from the Ganaraska watershed (over 65,000 acres) flowed into this one tight squeeze in downtown Port Hope,” observes Robin Long. Indeed, at its narrowest point – the Walton Street bridge – the riverbed was only about 40 feet wide. “No wonder we’ve seen so many floods.”

The Sears building wasn’t the only casualty that night in 1980. As the evening wore on, the disaster reached a climax when, not one, but two Walton Street buildings – on opposite sides of the bottleneck – collapsed under the unrelenting force of the water. On the east bank was a row called Torville Terrace, which contained a general store, delicatessen and law offices; on the west was the former fire hall, a gem of a heritage building with a four storey tower. Both were vintage Victorians and had held strong during earlier floods, but this time they were no match for the surging water. Their location on the water’s edge sealed their fate, for it was there that the flood was at its most furious. “I heard one of them go down, but at the time I didn’t know exactly what had happened,” recalls Sue, who was still marooned in her landlord’s apartment only footsteps away. It was probably the scariest moment of the entire ordeal.

Sue recalls that the flood started to subside in the wee hours of Saturday morning and everyone stranded in her landlord’s apartment finally relaxed enough to fall asleep. The next morning, she looked outside to see her pickup was still parked in front of the house. “But we couldn’t go anywhere, because the street was washed away.” The flood had gouged a six-foot-deep gulch in front of the house; the rear wheels of the truck teetered over the brink.

It was a jaw-dropping sight and Sue expected the worst when she and her husband finally ventured downstairs to survey the damage to their basement apartment. Surprisingly, no windows were broken. “You could easily make out the high-water mark in our living room, about four feet high on the wall.” There was mud everywhere. “We grabbed shovels and mops and started cleaning up. ”Meanwhile, volunteers appeared out of nowhere, eager to help.

In fact, hundreds of people showed up to lend a hand but few were prepared for the view that awaited them. Bricks and debris were everywhere: a car rested on the riverbed, the railings on the Walton Street bridge were missing entirely, new apparel from Riesler’s clothing store had washed down Queen Street and snagged against trees and parking meters. “But worst of all was the sight of the two collapsed buildings on Walton Street,” says Kathryn McHolm. The back wall of Torville Terrace was blown out to reveal a patchwork of rooms and furniture as if the building was a life-sized dollhouse. The fire hall was even worse, the south-east corner missing entirely, its second and third floors dangling precariously in mid-air. There was talk among heritage preservationists that perhaps the hall could somehow be preserved – in fact, only two weeks earlier, plans were announced to rehabilitate the building – but with public safety in mind, both the fire hall and Torville Terrace were quickly condemned.

Port Hope acted fast. The day after the flood, council met to figure out a strategy, keeping an eye not only on the three destroyed buildings, but also on four others that suffered serious damage. Engineers checked roads and bridges for structural integrity. In all, initial estimates pegged losses at about $10 million, divided equally between public and private property. Immediately, an emergency fund was established and the town asked the province to declare Port Hope a disaster area, thus leaving the door open to matching funding from Ontario government coffers.

For some, the flood was done and dealt with easily. Robin Long was back in business the following Monday. Kathryn McHolm’s shop was open after a week or so of slopping mud out the front door, but it was at least a month before Sue Town was nestled back in her apartment. Meanwhile, the fire hall and Torville Terrace disappeared, leaving a noticeable gap-tooth in the Victorian streetscape that still exists. A new building went up on the Sears site (now a bulk food store). And the town began to implement its plan to widen the riverbed. In 1982, there was grumbling that the province had yet to cough up a dime for the reconstruction effort, but by 1985 the last vestiges of the flood were all but gone. That year, new bridges were finally completed and Port Hope at last put the destruction of its worst flood behind it.

Or did it? Every year since, Port Hope has commemorated its sometimes tempestuous relationship with the Ganaraska River with an annual celebration called Float Your Fanny Down the Ganny. (This year’s event takes place April 18 – see floatyourfanny.ca) It’s a day of kayak and canoe races, but the highlight has to be the “krazy krafts,” makeshift floating contraptions that aren’t exactly seaworthy but nevertheless make for an extraordinary day’s journey on the water. It’s an occasion on which almost everyone gets wet. But amid the merriment, more than a few stop for a moment and ponder the dark side of this usually friendly river.

Could It Happen Again?

THE 1936 AND 1937 FLOODS inspired some preventative action at flood control, mostly reforestation in the upper Ganaraska watershed to better control the rate at which rainfall finds its way to the river. But the 1980 flood was the last straw and the town decided it was time to do something once and for all. And thus began the biggest excavation project Port Hope had seen since it first dredged the harbour in the 1850s. It would cost an estimated $5.9 million.

The idea was to blast a much deeper channel all the way from Bedford Street to just above the river mouth,that is, through the most vulnerable parts of the downtown. Significantly, the plan also widened the riverbed to 30 metres, eliminating the notorious bottleneck. This new channel was more than twice as deep and three times as wide as the natural riverbed. Three new bridges were built, each a longer span than the ones they replaced. Moreover, the adjacent lands were landscaped as parkland and most of the buildings that stood on the floodplain were demolished, including a gas station, a car dealership and Sue Town’s bungalow. In all, the new channel was said to be able to handle conditions similar to those in 1980 without incident.

So could it happen again? We’ll probably have to wait another hundred years to know for sure, but this writer, who lived on nearby King Street in the late ’80s, recalls walking his dog in the wee hours one April night, only to hear the midnight silence broken by the roar of the river below. Without warning, the new channel was surging and filled within inches of capacity. The flood controls were definitely put to the test that night; what might have been another disaster seemed to pass with hardly anyone noticing.

Story by:

Tom Cruickshank