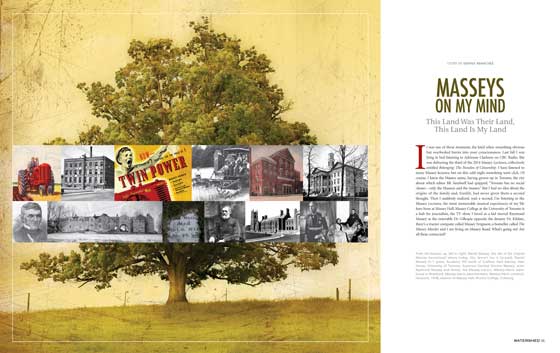

This Land Was Their Land, This Land Is My Land.

It was one of those moments, the kind when something obvious but overlooked bursts into your consciousness. Last fall I was lying in bed listening to Adrienne Clarkson on CBC Radio. She was delivering the third of the 2014 Massey Lectures, collectively entitled Belonging: The Paradox of Citizenship. I have listened to many Massey lectures, but on this cold night something went click. Of course, I knew the Massey name, having grown up in Toronto, the city about which editor BK Sandwell had quipped, “Toronto has no social classes – only the Masseys and the masses.” But I had no idea about the origins of the family and, frankly, had never given them a second thought. Then I suddenly realized, wait a second, I’m listening to the Massey Lectures, the most memorable musical experiences of my life have been at Massey Hall, Massey College at the University of Toronto is a hub for journalists, the TV show I loved as a kid starred Raymond Massey as the venerable Dr. Gillespie opposite the dreamy Dr. Kildare, there’s a tractor company called Massey Ferguson, a bestseller called The Massey Murder and I am living on Massey Road. What’s going on? Are all these connected?

Feeling at the centre of a weird Massey gyre, I had to learn more – and trust me, there was more, lots more. As a huge fan of Charlotte Gray – if you live in Watershed territory you have to read Sisters in the Wilderness about Susanna Moodie and Catharine Parr Traill – I began with The Massey Murder: A maid, her master, and the trial that shocked a country. When I got to page 58, I read that the Masseys were Yankee Methodists who came up from Vermont in 1802 and homesteaded north of Lake Ontario, close to the little port of Cobourg.

What? Cobourg, or more precisely, Grover’s Tavern, as Grafton was then called? The tractor dynasty originated in my backyard? I had passed the cemetery at the top of Academy Hill almost every day, without thinking twice about it. Until Gray’s book stopped me in my tracks and I finally pulled over and wandered among the graves. Rebecca, Daniel and their many descendants…names chiselled in stone, some eroded almost beyond recognition. So many pioneer Masseys buried on this hill with its sweeping view down to Lake Ontario, rugged people who cleared this very land, felt the topographic undulations with each step, experienced the stillness and the howling wind, the juncos, jays and crows, the snow dunes of winter and chartreuse of spring, the heartbreaking shafts of sunlight on Lake Ontario. I am walking in their steps, wondering what drove Daniel, Rebecca and their four young children north in 1802. Why did they leave their well- established brethren in New England and cross the lake to Grover’s Tavern? Who were these people whose ancestry went back to Puritan Salem and before that, Cheshire, England?

THE BOOK OF TREES

In an 1889 red brick house on Community Centre Road east of Baltimore, Carman Massey, 78, pulls out a large blue book: The Massey Family, 1591-1961, compiled by Marian Massey Nicholson. “Seven of us were born in this house, five sisters and a brother,” he says in a low, slow voice. Carman, the youngest in his family, is the great-great-great grandson of Daniel Sr., the one I’m looking for, the one who came north and left his 11 younger siblings in the States. “There are family trees for all of them in there,” says Carman’s wife Helen, who’s taking a break from her sewing business to help me out with this.

I open the book and am instantly confused. Trees? More like the Ganaraska Forest. These people were prolific (nine or 10 kids was the norm), and if one of the children died young, they often reused the name for the next in line. The number of Daniels, Harts, Jonathans, Rebeccas and Samuels is a nightmare of genealogy.

Carman’s 100-acre mixed farm came down through Daniel Sr.’s eldest son Jonathan. And it was Jonathan’s eldest son Samuel, who built the original stone house that has now expanded into Ste. Anne’s Spa. I cannot begin to chart this line, but the story is well told by Patricia Sullivan in the Massey section of steannes.com/history, complete with lot and concession numbers.

I try to conjure Daniel Sr. and his wife Rebecca clearing the land at the top of Academy Hill near the current spa, building a log cabin, hauling rocks out of the ground, cultivating, planting – all by reddened hands. It’s said that land was cheaper here than in New England, but Daniel must have been motivated by more than this.

What drives some siblings to leave the familiar and comfortable, to want a different life? In this case, maybe he wanted to get away from the expectations of a huge and successful family and figure out who he was, independent of them. He was clearly a risk-taker and confident enough in his muscle and mental smarts to consider deviating from the family norm. Plus, he had vision, determination and energy, qualities inherited by many of his offspring. And they were driven Methodists too, all about hard work and no fun, embodying John Wesley’s teaching: “Do all the good you can. By all the means you can. In all the ways you can. In all the places you can. At all the times you can. To all the people you can. As long as ever you can.”

To the point where some of them dropped dead trying! But that’s further on in the story, during the evolution of the Massey Manufacturing Company, from its beginnings creating iron tools for neighbours in these hills to, in 1891, being the largest maker of agricultural equipment in the British Empire.

According to the 1808 census, Daniel Sr., 42, had 30 acres under cultivation, as well as three horses, four oxen and two milk cows – all told, £82 worth. Not bad after six years of grinding work. Then came the War of 1812, a crucial turning point. Daniel Sr. and his two eldest sons were called to fight for the British (and against their American cousins). His youngest son, Daniel Jr., a mere 14, stayed back to help his mom and three sisters run the farm. Turned out, he was to management born. “The family’s horses had been taken for the army, so he broke in two young steers to take their place,” writes Patricia Sullivan in her Massey family history. “He hired farmhands to help with the harvest, took grain to market and settled accounts.”

Like his father, Daniel Jr. had an independent streak and was not content to be the dutiful son and stay on the family farm (heresy at the time). At 19, he left home to build his own life – and was promptly disinherited. “For the first few years, he employed teams of men who were hired out to clear land for other farmers,” writes Sullivan. “When he eventually settled down to farming, he owned over 1,000 acres and built a fine home west of his family’s homestead in an area known as the Gully.”

FORGING AHEAD

What happened next is a tale of ingenuity, opportunity and shrewd business sense. Daniel Sr. had impressed upon his children that farmers had to become businessmen if they wanted to get anywhere. “Masseys move,” he said. “Remember, we’re movers.” Daniel Jr. finally took a step down that road at age 49; he moved to Bond Head and formed a partnership with a friend who operated a small foundry. He was going to make tools for farmers rather than spend all his hours behind a horse team and plow. He could see a big future for labour-saving devices, and his timing was perfect: the Industrial Revolution was roaring around the world, the Grand Trunk Railway was opening up vast markets, and protective tariffs made it almost prohibitive for American manufacturers to sell their machinery in Upper and Lower Canada.

Fortunately, Daniel Jr. also had a strong and supportive wife, who was prepared to pick up and move. The Massey men had a habit of crossing the lake to find their partners, keeping the Yankee can-do spirit in the gene pool to infuse subsequent generations. Daniel Jr. married Lucina Bradley of Watertown, New York in 1820, and they went on to have seven children (five girls and two boys). The second eldest was Hart. Hart Massey. Ring any bells? He’s the business visionary, skilled at engineering, research, development, marketing, mergers and acquisitions. He’s the one who took his dad’s design ideas and built an international company, and then returned a big chunk of his assets to the public.

Born in 1823, Hart Massey grew up on the family farm in the Gully. In a 1978 CBC documentary called, The Masseys, Chronicles of a Canadian Family, Lovat Dickson says, although Hart was raised on the farm and knew the meaning of hard work from childhood, his mother recognized he wasn’t cut out for agricultural life. She stressed the importance of education, and he and all of his siblings learned reading, writing and math. The value of learning was further driven home by Methodist circuit riders – saddlebag preachers – who travelled the country- side on horseback providing a larger view of the world to settlers whose lives were defined by the relentless work of taming the land. One such preacher urged Hart to “look up over the hill, see beyond”, and gave him a book of mechanics – which got the gears of the teenager’s mind turning.

I love this simple summary sentence of Charlotte Gray’s: “Massey men shared a valuable talent: an aptitude for fiddling around with bits of metal.” From fiddling with metal, they went on to invent new farm machinery, buy a larger foundry in Newcastle, have their company chosen to represent Canadian manufacturing at the 1867 Paris Exposition, win gold medals there, expand the business to Europe, grow it further until it burst out of 10 buildings in Newcastle, erect a state-of-the-art factory on a six- acre site on King Street in Toronto, make a fortune, build a concert hall in memory of the cherished son who worked himself to death at 36 managing the company, establish the Fred Victor street mission to honour another son who died young, leave a will that dictated most of the estate be disposed of for the benefit of public institutions and causes, produce heirs who create a family foundation which funds a refuge of recreation and reading at the University of Toronto (Hart House).

Vincent Massey was the grandson of Hart and the brother of Raymond Massey, the actor. After serving in the first world war and running Massey- Harris in the early 1920s, Vincent moved into politics and public service and went on to lead a royal commission on the arts from 1949-51 (The Massey Report), establish the Canada Council for the Arts and the National Library of Canada, become the first Canadian-born Governor General of this country, introduce the Governor General’s Awards, endow and help found Massey College at U of T and initiate the Massey Lectures, considered the most important public lecture series in Canada. Vincent retired to his Batterwood estate in Canton in 1959 and is buried in St. Mark’s Cemetery in Port Hope. There are 23 Canadian schools named after him.

The impact of this family on Canadian business and culture is staggering, which brings me back to my radio revelation last November and the lecture given by Adrienne Clarkson, 26th Governor General of Canada. She would not have been delivering that lecture were it not for the vision and financial support of the Massey Foundation and Vincent, in particular.

All this from homesteading north of Grafton and having a fondness for fiddling with metal. The Masseys have had a central role in creating our national identity through the arts and the promotion of public discourse about important ideas, in help- ing us understand who we are as citizens of Canada. Clarkson’s subject was the meaning of citizen- ship, and she defined it as “a commitment to helping advance the aims of our society in whatever way we are called upon to do so”. There’s such a loud echo of Wesley in this, the Daniels would be smiling in agreement at doing “all the good that you can, for as long as you can”.

My head is exploding with the web of connections I’ve discovered out my back door in the past six months, from the weathered headstones up on the hill where Daniel Sr. and Rebecca Massey lie buried, through the extraordinary contributions of their descendants (each one, a powerful story on its own), full circle to a radio broadcast about our role as citizens in shaping our country. There is so much to think about, to initiate, to do. I am humbled and inspired by the family whose name is on the modest green sign at the end of my road.

The Murder

A HUNDRED YEARS AGO, on February 8, 1915, 18-year old Carrie Davies shot her employer, Charles “Bert” Massey, as he was walking up to his Walmer Road house in Toronto after work. Charlotte Gray tells the story in captivating detail in her 2013 book, The Massey Murder: A maid, her master, and the trial that shocked a country. And the drama of the trial is deftly interwoven with the social history of Toronto, the Great War and the nascent women’s movement. A fascinating read.

Bert was the fourth of the five children of Jessie and Charles Massey, the eldest son of Hart. It was workaholic Charles who headed the Massey Manufacturing Company from the age of 23 until his death from exhaustion and typhoid in 1884. Though astute at business, he had a gentler management style than his stern dad, knew all his employees and, as an accomplished organist, brought his passion for music to the plant. He even created a Massey Band, String Orchestra and Glee Club.

Though Hart was devoted to Charles and devastated by his death, he did not treat his son’s widow and children with generosity. Four year-old Bertie and his siblings became the poor cousins of the Massey clan. Yes, they inherited some money and went to the right schools, but at the time of his murder, Bert was a car salesman, had a teenage son and a wife who preferred spending time with her family in Bridgeport, Connecticut rather than socializing with Toronto’s nouveau riche.

Carrie Davies was a domestic servant for the Masseys, and ever wary of the liberties employers often took with their maids. Her reputation was all she had; once defiled, she would have no choice but to turn to the street for a living. Carrie was right to be worried. The night before the murder, Bert had crossed the line.

“He took advantage of me yesterday, and I thought he was going to do the same today,” Carrie said in her statement to the police. “He caught me on Sunday afternoon and kissed me twice. I ran upstairs; then he called me to make his bed, and I obeyed. As soon as I went into his room, he said ‘This is a nice bed.’ He caught me. I pushed him aside and ran upstairs. I dressed and went out and told my sister on Morley Ave.”

The next evening when Carrie saw her employer returning from work, she ran to get the revolver from Bert’s son’s bedroom, loaded it with five cartridges and fired at Bert Massey as he was coming up the front walk. The police arrived soon after and took Carrie to the station, where she immediately confessed.

The murder was ammo for a newspaper war already underway in Toronto, which had six papers vying for readers’ attention, two of which gave this story lakes of ink. On the side of the Masseys was handsome Joe Atkinson, editor of the Toronto Star, the voice of modern capitalists like the Eatons. On the other, was the Evening Telegram, owned by John Ross Robertson and the voice of the working class.

Carrie’s brilliant and eloquent lawyer Hartley Dewart (acting for her pro bono) entered a plea of not guilty, arguing that his client was the one who had been wronged and that she had acted in self-defence. The prosecuting attorney, Edward Du Vernet, wanted a conviction of manslaughter because Massey had not actually assaulted Davies. Dewart prevailed: In his final address to the court, he righteously pronounced: “It was not manslaughter, it was brute slaughter!” It took the 12-man jury only 30 minutes to acquit Carrie Davies.

The case was perceived as a triumph for women’s rights, although the decision was contentious in the legal community. And needless to say, the Massey family was not pleased. In a way, it was the Dewart family settling an old grievance with the Masseys, a story that has huge Northumberland resonance.

Hartley Dewart, Carrie’s lawyer, was the son of poet, Methodist preacher and teacher E.H. Dewart, who was also editor of the Christian Guardian and a regent of the Methodist Victoria College in Cobourg. Hart Massey was a huge supporter of the college, having been a serious student there, and claiming his mind had been shaped by it. But in 1888, E.H. Dewart and Hart went head to head about federating Victoria College with U of T, a move Dewart deemed necessary to ensure a Methodist moral influence in Toronto university life. Hart was opposed to the idea, and “regarded the proposed move as an Anglican takeover of the school,” writes Gray. He tried to block it by offering $250,000 to keep Victoria College in Cobourg, but the move went ahead in 1890. According to Gray, the Toronto press fed on this dispute and in the process “savaged all Methodists, including both Hart Massey and E.H. Dewart.” E.H. was enraged that his reputation had been sullied, and the fire of injustice still burned in his son, Hartley, long after the elder Dewart had died. Hartley was happy to take on the Carrie Davies case for free – and exultant at his victory.

Parenthetically, it’s interesting to ponder what Cobourg would look like today if Hart Massey had succeeded in keeping Victoria College in the town. A beautiful lakeside community, an hour by train from downtown Toronto, anchored by a university. What a compelling image.

Story by:

Denny Manchee