The fate of Brookside and the thirty-two-acre parcel of land that surrounds it, lies in the hands of the Town of Cobourg and the provincial government.

The former Brookside Youth Centre in Cobourg awaits new residents and new uses. Which of the many possibilities will be in its future?

At the far east end of Cobourg’s King street, past Victoria Park and before the “feel-good” town quietly thins out along Highway 2, lies a rolling green space with centenarian trees and a tidy cluster of buildings. A creek runs through the thirty-two acres, flanked by fragile floodplains. In the centre of it all stands an imposing Beaux-Arts mansion that has spent the last 143 years adapting to its varied owners.

Until recently this stately property was the Brookside Youth Centre. It now stands idle and empty, and the future of the white-columned mansion, Strathmore House, and the property surrounding it has sparked great interest among town residents.

After 53 years of operating as a youth detention centre, Brookside was closed by the Ontario Government in February 2021. At the time the facility was grossly under-utilized, with just 5 youth, 106 staff, and annual expenses of $10 million. In March, MPP for Northumberland-Peterborough South David Piccini invited the public to share their visions for repurposing the site. To date, the new Minister of Environment, Conservation and Parks has received nearly a thousand proposals from a diverse range of groups. The zoning bylaw for possible institutional uses allows for a college, art gallery, daycare, medical clinic, public stadium, retirement home, private club or wellness centre; nevertheless, the overriding themes among the proposals are for affordable housing and arts and culture use.

BRINGING HISTORY INTO THE 21ST CENTURY

Long before it was the administrative hub of a correctional facility, Strathmore House was a summer residence. Judge George Mackenzie Clark, a politician and friend of Sir John A. Macdonald, bought the original 180 acres in 1869. He severed and sold the land but retained twenty-four and a half acres, and in 1878, Strathmore House was recorded on the site, according to documents housed in the Cobourg Public Library. Clark sold the property to Charles Donnelly, a wealthy American from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. After Donnelly’s death in 1906, the estate fell into the hands of a Pennsylvania trust company. It was eventually sold to Torontonian Stephen Haas for $28,000 in 1918 and remained a summer home for the next two decades.

The Ontario Government leased the property in 1943 for a girls’ training school and later purchased it and altered the facilities to become the Ontario Training School for Boys. It was renamed Brookside School four years later in an attempt to remove the stigma associated with “training school.” In 1968, it became a secure detention centre for male youth. Modern buildings were added in the early 1970s and included four living units; of those, David Piccini says that one remains fully operational, one requires repair, and two are basically non-operational. Today, Strathmore House is municipally listed as a heritage site, a way of reminding the province that the property has cultural heritage value to the community.

A CENTRE FOR ARTS, CULTURE AND COMMUNITY

There’s a burgeoning vision to convert Brookside into a cultural hub to foster creative collaboration and development in arts and culture. Fourteen local arts organizations – including Film Access Northumberland, Marie Dressler Foundation, Northumberland Orchestra and Choir, Oriana Singers of Northumberland, Victoria Opera Society, Northumberland Players, Sounds of the Next Generation, and the Art Gallery of Northumberland – are making the case for a much-needed space for arts education, performances and programming, as well as storage for valuable props, costumes and equipment.

The groups look to Toronto’s Artscape Youngplace as a prime model for uniting community and cultural resources, heritage preservation and environmental leadership. Artscape is a not-for-profit urban development organization that makes space for creativity in communities. In 2013, through public-private partnerships, they transformed the old Shaw Street Public School in the Queen Street West area into a cultural hub that continues to generate revenue through events, memberships and rent.

Public support in Cobourg dates back to the 2013 Downtown Vitalization Action Plan, when 80 per cent of residents surveyed felt it was “somewhat or very important” to have a performing arts and cultural facility. Additionally, 30 per cent listed a youth centre as the most important downtown improvement. “Brookside could act as a place where youth could be mentored,” says Carol McCann, former chair of the Downtown Coalition Advisory Committee, who conducted the survey. “There could be a thriving youth drop-in centre alongside arts facilities, like Artscape.”

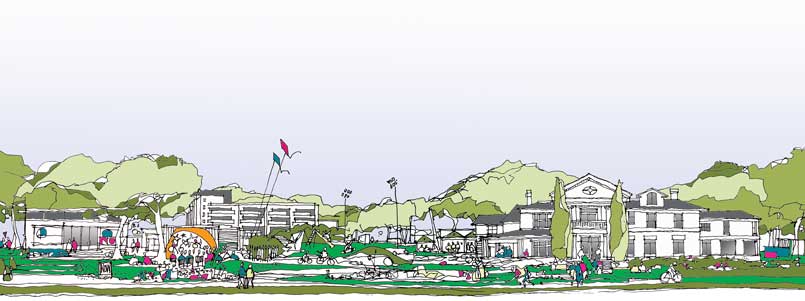

The collective proposal envisions the sixteen buildings on the property becoming a trade school for hospitality with a commercial kitchen and community garden, an arts campus with lecture halls and a performing arts centre, and a branch of the Ontario College of Art and Design (OCAD). The need for additional creative space in Cobourg was identified in the town’s 2019 Cultural Master Plan, which calls for investing in facilities for cultural development, training opportunities, and experiences for youth.

Arts and culture are a vital driving force for local economies. The sector accounts for more of Ontario’s GDP than the energy industry and the agriculture, forestry and mining sectors combined, as reported by Toronto Arts Facts. A 2005 Montreal study looked at how regional economic growth is powered by creative people, and found that those people prefer places that are diverse, tolerant and open to new ideas. The more creative clusters there are, the more there’s a “creative class,” a concept crafted by Richard Florida, an American urban studies theorist at the University of Toronto, who says cultural attractions and artist visibility invite investment.

“We think Brookside would be a wonderful opportunity to bring all of the arts groups in our communities together. Not only to thrive individually but to promote multiplicity of efforts and product by working and partnering together in a space where we’re all co-located,” says Ross Pigeau, chair of Film Access Northumberland, a nascent not-for-profit promoting the film arts, educating young filmmakers, and expanding perspective on today’s issues by looking at films to prompt tolerance.

“There’s a big emphasis on the middle word, ‘access,’” says Ross. “We want Northumberland to access all of the film arts out there and we want the film community to access the great arts that are thriving in Northumberland.”

Filming brings colossal funds to small towns. When Netflix producers rolled into Cobourg to film Ginny and Georgia in 2019, they hired local services and compensated businesses while King Street was closed for filming. They left The El restaurant with a fresh coat of paint and a new awning, and attracted droves of tourists. Art galleries stimulate local economies too, through consumer purchases and tourism. According to the Ontario Association of Art Galleries, every dollar invested in galleries sees a four-dollar return.

“We think Brookside would be a wonderful opportunity to bring all of the arts groups in our communities together.” ROSS PIGEAU,

FILM ACCESS NORTHUMBERLAND

“Galleries and museums are powerful tools that engage communities,” says Olinda Casimiro, Executive Director of the Art Gallery of Northumberland. For the future of Brookside, she says the AGN would develop a sustainable business model to align with other interested partnering organizations, especially those in arts and culture. “Galleries are a means to public dialogue, they contribute to the development of a community’s creative learning, and create healthy communities capable of action, building capacity and leadership.”

As noted in Cobourg’s Cultural Master Plan, the majority of 270 local cultural enterprises are individual artists, and government statistics may not fully capture volunteers and part-time roles in cultural work because they typically “fly under the statistical radar.” Consequently, any measurable data would underestimate the economic impacts of cultural activity. Still, with local creation industries at 31 per cent compared to the province’s average of 54 per cent, the plan proves Cobourg is a favourable location for artistic talent and cultural sector growth.

“We’re needing to think outside the box to support the arts community post-COVID,” says Carol McCann, describing an interdisciplinary approach to thinking about the arts so that one effort can work with another. For example, the costumes of Northumberland Players could be more readily available to visiting film productions, and Strathmore House could serve as a single, streamlined administrative hub for arts organizations. “The Cultural Master Plan calls for several strategic actions that are pertinent here,” she continues, “and one of them is to invest in cultural facilities to anchor cultural development in Cobourg. Clearly the acquisition of Brookside by the town would hit that bang on.”

A SUSTAINABLE, HEALTHY NEIGHBOURHOOD

Among the other proposals for Brookside, the vision for Strathmore House as a cultural and youth centre is popular. A group of citizens called Brookside + Company sees this as a once-in-a-lifetime chance to create a sustainable, affordable, inclusive and healthy neighbourhood to serve both its own residents and the 600 homes in the area. Keith Oliver, an 84-year-old retired architect, says the group envisions Brookside transformed by mixed housing, inclusive of a cultural hub, a pedestrian market, and a community garden. And they’re looking to youth to lead the way. He says a neighbourhood site plan could be the result of a competition similar to the Urban Land Institute’s Hines Student Competition in the US, which was recently won by a Canadian university team.

“We simply do not have healthy neighbourhoods anymore, and a majority of youth do not believe they have a better standard of living than their parents,” says Keith, who grew up in Montreal, lived in Manchester, England, and is pushing for building technology that harkens back to modular housing. Over 50 years ago he worked on Habitat 67, a project built for Montreal’s Expo 67 by Israeli-Canadian architect Moshe Safdie, who reimagined the stacked apartment building as staggered living spaces linked by rooftop gardens. The concept caught on internationally, but not here, despite a Toronto undertaking demonstrating a 30 per cent reduction in building time and cost. In 2019, a revival of Safdie’s iconic buildings began in Asia. Keith calls them a perfect prototype for innovative, affordable housing.

There are 900 families waiting for affordable housing in Northumberland County, according to the Cobourg Non-Profit Housing Corporation. People are waiting ten years for one-bedroom homes and up to five years for two- and three-bedroom homes. Keith says we’ve outgrown the postwar vision for a promising future and it’s time for forward-thinking ideas to take hold, even decades later.

Brookside + Company sees this as a once-in-a-lifetime chance to create a sustainable, affordable, inclusive and healthy neighbourhood.

“I live on a very nice street of downtown Cobourg and there are almost no families here,” says Keith. “Very few people know each other. And of course, we travel around in cars, isolating ourselves from the rest of the world. I’ve thought about these issues all my life.” Of the inclusive neighbourhood and cultural centre he has no doubts, adding, “This is worth doing.”

THE BALL IS IN THE GOVERNMENT’S COURT

Before the Town of Cobourg can purchase or engage in partnership for all or some of the site, the province must first decommission the property, a process that is underway to look at environmental remediation and buildings that are not safe. Brookside + Company had the soil tested at Guelph University and approved for organic gardening and has consulted the Ganaraska Conservation Authority about the floodplains. Still, what are called hazard lines pose a pricey concern for the Town of Cobourg. Mayor John Henderson says it can cost $80,000 to $100,000 to maintain the small strip of creek so that it meets new environmental standards.

“It’s going to take multiple units working in unison to own and best develop that beautiful property and still be respectful of the future and of serving our past.” COBOURG MAYOR JOHN HENDERSON

“I look at Brookside as a campus site that has multi-facets, with each enriching the other in an integrative way … out in the community with different organizations, institutions, for-profit and not-for-profit,” says Mayor Henderson.

The province must also consult other government ministries and agencies, who could claim the property. And it’s vital to consult Indigenous communities about Williams Treaty commitments to ensure rights aren’t adversely affected. So far, whether for health care, long term care, or affordable housing, no ministries have expressed an interest, except for David Piccini’s Environment Ministry in response to a keen public interest in nature conservation.

COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT LOOMS LARGE

“I suspect the provincial government will want to get market value for the property,” says Mayor Henderson, adding that while the arts and culture interest in Brookside is worth exploring, he’s seeking partnerships interested in affordable housing. “A lot of groups believe we’re just going to inherit this property, that the province is going to donate it. That’s not going to happen,” says the mayor, noting the millions of dollars being considered for protecting the waterfront and the east pier.

“We’re going to get one really good shot at this site and we better be prepared, because if it gets to open market, there could be a number of individuals or developers with deep pockets who may be very interested,” he says, wondering if the next twenty years of developing eastward could see the centre of Cobourg shift from the five corners to where Brookside stands. “It’s going to take multiple units working in unison to own and best develop that beautiful property and still be respectful of the future and of serving our past.”

WHITHER BROOKSIDE?

Councillor Nicole Beatty is Coordinator for Planning and Development Services and motioned in 2020 to ask the province for an update on the status of Brookside. “I see that site as an amazing way to create a next-generation thinking of an integrative community, both of creative place-making and living, and connecting with nature while protecting the assets,” she says. “Housing can’t drive it alone; arts and culture can’t drive it alone. The needs of the community and the potential of that site is what needs to drive an overall master planning of what Brookside can become.”

Ultimately, if there’s no interest from the province, and the community wishes to pursue public-private partnerships and Brookside goes to market, an order in council is required to sell the surplus property to a third party. “There’s certainly an interest in engaging planning expertise, because a property this size really requires some vision,” says David Piccini, noting the need for expanding green space to reach a 2030 target, and the need for affordable housing aligning with the government’s policy “More Homes More Choice.”

The MPP plans to provide feedback this fall and hopes to gain a clear vision for what’s to become of Brookside by the end of the year, promising no action will be taken without engaging the public. “It’s about how Brookside interacts with the town as a whole,” he says. “Arts and culture is an incredible priority. It was hit hardest and will take the longest to recover from COVID. But it must recover. It’s who we are as a people. It tells our story.”

Inevitably not everyone is going to see what they want to happen to Brookside. Fundamental to this effort is how the future of Brookside can enrich the local social fabric and economy. Nicole Beatty has volunteered for arts organizations and knows the feeling of being kicked down the line. “But I also think this council has strong arts and culture ambassadors. Unfortunately, a lot of momentum has had to take a deep breath through the pandemic. I wouldn’t want to see arts and culture lost in any potential future for Brookside, but I don’t think any sole purpose should be the driving factor in the vision for it.”

At the heart of the arts group’s proposal is recognition of the vital role that arts and culture play in enhancing economic development and the need for integrating culture, planning, and community services. Transforming Brookside to benefit the community in multiple ways while respecting the floodplains, green-space, and celebrating arts and culture certainly sounds like it could help maintain Cobourg’s position as a worthwhile, feel-good place to be.

Story by:

Elizabeth Palermo

Illustration by:

Paul Backewich