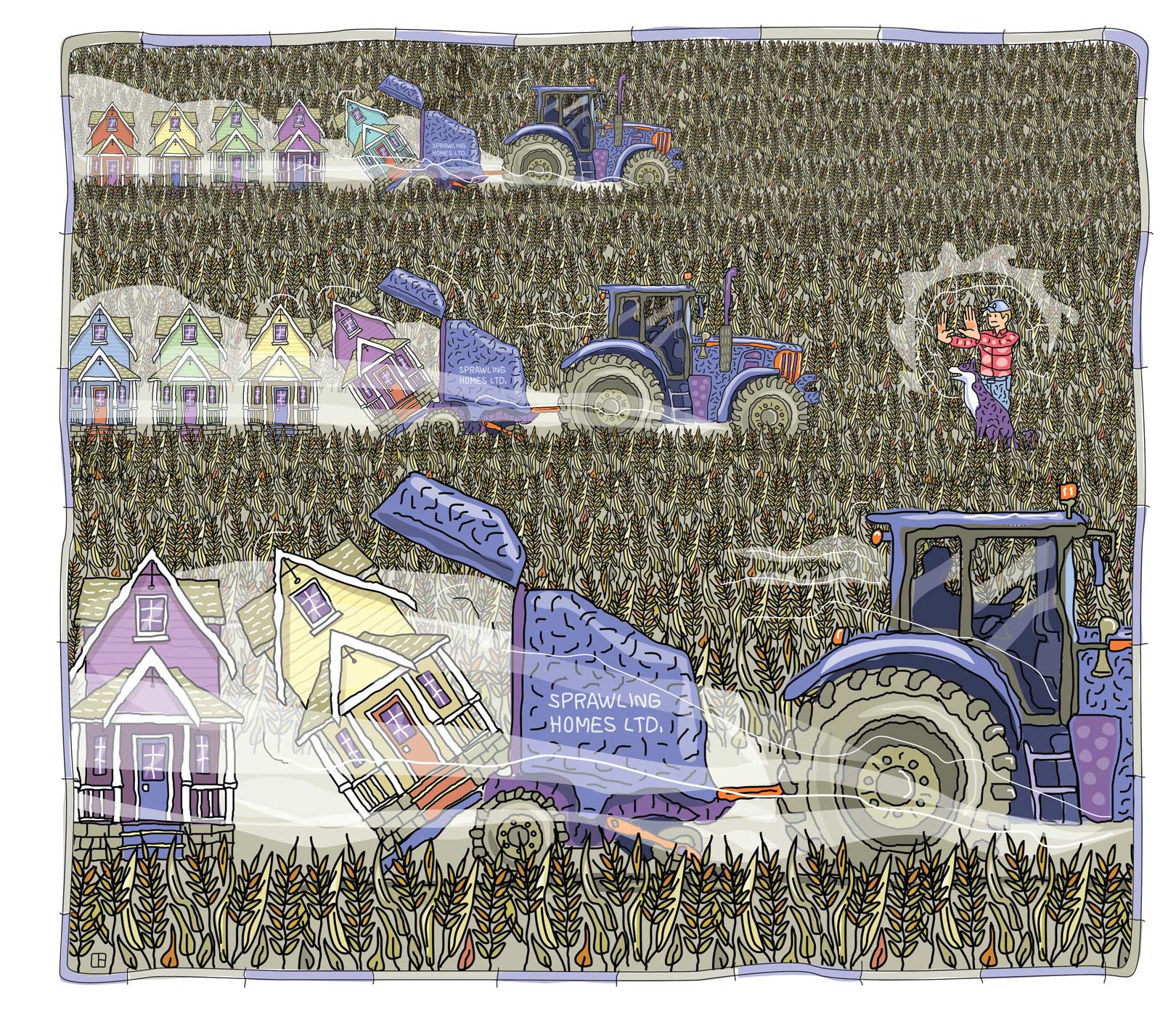

Farmland is disappearing at an alarming rate as development advances like a hungry caterpillar.

Above the chatter of a nesting swallow by the back door, he hears the incessant flow of traffic. His farm is sandwiched between Highway 2 to the south and the 401 to the north. A short distance away, he can hear the sound of heavy equipment as another subdivision creeps closer from the east. He worries about the future. What will happen to his land? Will his family be able to continue farming? His dog sleeps at his feet without a care in the world.

Lucky dog.

The people who cultivate the world’s food navigate obstacles on a daily basis. Talk to a farmer and you’ll hear of rising operating costs, scrutiny over agricultural practices that they understand better than their critics, casual attitudes to trespassing over their land, and the frustration of moving huge pieces of equipment along busy highways. In addition, they must answer to many levels of bureaucracy, facing spools of red tape. Talk about a tough row to hoe!

Thankfully, farmers are pros at adapting. Their eternal optimism, sense of humour and humanitarian qualities make for a unique breed.

But these days they face a challenge that may be insurmountable, a challenge that could devastate not only farmers, but all of us.

LOSS OF FARMLAND – STEAMROLLING LEGISLATION

Every day, Ontario loses 319 acres of farmland to non-agricultural land uses like urban development and aggregate extraction, according to the Ontario Farmland Trust. StatsCan’s Census of Agriculture reveals that in the combined counties of Northumberland, Prince Edward, and Hastings, there were 151,125 fewer acres of farmland in 2021 than in 2006.

Signs for new housing developments seem to pop up faster than weeds. The process to plant those signs involves the ground rules for land use: the Ontario Planning Act, municipal zoning bylaws, conservation authorities and public consultation.

A major threat to arable land is heading our way from the provincial government itself. Ontario’s More Homes for Everyone Act – Bill 109 – was passed in April 2022. It’s a complicated flurry of policy changes based on building 1.5 million homes over the next ten years. Then in November 2022 the provincial government passed Bill 23 – the More Homes Built Faster Act. This bill changed the Development Charges Act and the Planning Act and altered the method for determining development charges. The move was contrary to the accepted concept that growth should pay for growth; it is certainly a move away from environmental protection. Bill 23 also allows for the removal of 7,400 acres of farmland and greenspace from the existing Greenbelt. The offset plan was to add 9,400 acres of land to the Greenbelt in other areas.

Bill 97, or the Helping Homebuyers, Protecting Tenants Act is aimed at drastically reshaping development rules to address housing affordability and supply in the province. The bill loosens rules around farmland protection in Ontario. Farmers believe this would result in more homes being built on prime farmland, threatening the foundation of agriculture.

“Development and the high cost of farmland are impacting the future for farmers in Prince Edward County. I believe development needs to occur, but it’s happening on some of the best prime agricultural land we have.” JASON COURNEYEA

COMMUNITY VOICES

Bill 97 was passed in June, but the consultation deadline was extended because of voices from across the province and from the local communities.

In July this past summer, the Northumberland Rural Coalition hosted a community forum, “The Importance of Protecting Farmland in Northumberland County,” in partnership with Community Power Northumberland and the Small Change Fund. The forum’s outline states that the county “has a rich history of agriculture and is home to many family farms that have been in operation for generations. As the provincial government continues to upend the planning and development process – especially via its proposed Bill 97 – there are growing concerns that more Ontario farmland will be lost due to development. It is essential that county residents clearly understand the importance of protecting this valuable resource.” An enthusiastic audience voiced their combined concerns and expressed hopes for more consultation in the future.

Their voices are echoed by high-profile organizations such as the Ontario Federation of Agriculture (OFA), the National Farmers Union of Ontario and the Ontario Farmland Trust (OFT), as well as grassroots groups such as Hands Off The Greenbelt, Seniors for Climate Action Now! (SCAN!) and Blue Dot Northumberland.

DEVELOPMENT PRESSURES

The economy in Prince Edward County is strongly supported by agriculture, especially the wine industry and the resulting agri-tourism. The County’s success in attracting new residents has its benefits, but it is difficult for farmers to watch as the demand for new homes pushes onto farmland at a steady pace. “Development and the high cost of farmland are impacting the future for farmers in Prince Edward County,” says Jason Courneyea, a thirty-seven-year-old PEC farmer who is employed on a dairy farm. He and his wife cash crop a combination of owned and rented land. “I believe development needs to occur, but it’s happening on some of the best prime agricultural land we have.”

According to Dwayne Campbell, Manager, Planning and Community Development/Chief Planner for Northumberland County, agriculture is the number one employer and is the largest economic sector in the county.

“Due to its unique significance to our community’s character, lifestyle and economy,” Campbell says, “Northumberland County has been proactive in policies to protect local farmland.” He points out that over 31 percent of land in Northumberland is currently zoned as protected agricultural land.

But municipal zoning may not be enough. Enter the MZO.

A Minister’s Zoning Order, or MZO, allows the province to authorize development and bypass local planning decisions to expedite what it wants built. Although an MZO can be subject to a judicial review, only the province can rescind it and it can’t be appealed. The concept of an MZO is that it should be used in emergency situations (for instance, the pandemic) to facilitate construction that would otherwise be tied up by bureaucratic red tape. If abused, the MZO machinery can also push through development regardless of public or environmental concerns.

The Ontario Federation of Agriculture has raised objections to the unprecedented use of MZOs in municipalities that already have robust land-use planning systems. According to Drew Spoelstra, OFA vice president, “MZOs have been used to quickly advance sprawl-induced housing developments, leading to further loss of farmland in Ontario. Since 2019, 2,000 acres of farmland have been lost to MZOs. Once land has been developed and paved over, it is lost forever.”

Spoelstra believes fixed, permanent urban boundaries will help limit the loss of agricultural land. “By redeveloping vacant or underused space, utilizing areas with poor soils or drainage, reinventing existing infrastructure, or building higher density development, we would be able to preserve Ontario’s productive land for food production.

“Urban intensification can protect agricultural land, by boosting economic growth, creating new jobs, providing affordable housing options, supporting municipal infrastructure systems, ensuring food security, and contributing to environmental stewardship.”

The Ontario Farmland Trust is another community voice that upholds the protection of farmland. Formed in 2002 by farmers, land conservationists, planners and academics, its mission is “to protect Ontario farmland and associated agricultural, natural and cultural features of the countryside”. It’s “an organization with the unique ability to support grassroots, farmer-led and community-driven action on farmland protection”.

Margaret Walton (OFT board chair and a speaker at the July 29 forum) states, “We need to rethink how we manage growth. We need to permanently protect our unique productive land base.

“The lack of land is a constraint to our future farming viability. Much of the land is still there, but because of the demand for building lots, it has become too expensive for agricultural uses. The solution is either to build new communities in non-agricultural areas, or more practically, to allow expansion of urban boundaries, but only onto non-agricultural land. Those areas do exist, and efforts should be made to encourage development there.”

According to Ontario Farmland Trust Chair Margaret Walton, forty percent of farmers are set to retire within the next ten years, and sixty-six percent do not have a succession plan in place.

A BALANCING ACT

On August 9, Bonnie Lysyk, Ontario’s Auditor General, issued a report harshly criticizing the provincial government’s processes for development of protected land. This could be a step in slowing a path of potential destruction through Ontario’s Greenbelt.

As the MPP for Northumberland-Peterborough South, Ontario Minister of Environment, Conservation and Parks, David Piccini is aware of the plight of the farmer. Piccini stresses the importance of balancing the province’s agri-food sector with the need for growth in rural Ontario, including infrastructure and technology. “Through the Grow Ontario Strategy, our government will strengthen the sector by ensuring an efficient, reliable, and responsive food supply and increasing competitiveness. I will continue to work with local farming organizations like the NFA and value their ideas and partnership.”

To MPP Piccini’s point, there is room for both agriculture and settlement – or there should be – provided there is thought and foresight. “The people in town need the farmers, and the farmers need the people in town,” says the common-sense voice of Jason Courneyea.

EROSION OF FARMLAND

The eighth-generation Crews family operate a dairy farm on about 500 acres in Quinte West. Thirty years ago, Brian Crews recognized the challenges ahead and decided that even with a degree in agriculture, off-farm employment was the most secure way to provide for his family. Crews is a City of Toronto firefighter (he works 24-hour shifts), who is also a Northumberland Federation of Agriculture (NFA) director.

He recalls that up until the 1970s, most of their neighbourhood farms were small operations with dairy cows and an apple orchard. Most farmers could work 100 acres and make a living. As technology, regulations and markets changed, coupled with a declining workforce because of smaller families, the farms that didn’t adapt simply became too uneconomical to continue. “Today our farm produces more milk with fewer acres than was produced on the whole road fifty years ago,” he says. The farms that survived by modernizing their production methods remained profitable.

Many of the farms that didn’t adapt to changing agricultural practices have been severed, leaving behind parcels of land that are simply not large enough to be viable farm operations.

But as the current information indicates, farmers are an aging demographic, and often their families aren’t interested in continuing in agriculture. As a result, their retirement relies on either severing a few lots from their farm or selling the property outright to a developer.

SUCCESSION AND PROTECTION

In the vocation of farming, succession – the question of who will carry on farming into the next generation – is a pressing concern for many.

OFT’s Chair, Margaret Walton, observes that forty percent of farmers are set to retire within the next ten years, and sixty-six percent do not have a succession plan in place. Without a successor, usually from the farm’s family, properties from retiring owners can fall prey to developers, speculators and non-farmers, which will inevitably reduce available farmland and drive prices up.

The OFT offers a practical solution: the Trust can act as a land bank for farmers and landowners who don’t know what else to do with their property but who want to see it permanently protected for agricultural use; this can be done through easements, which protect land and make it more affordable for a new generation of farmers. Walton points out, “Ontario is one of only a few provinces with a farmland trust, which holds farmland conservation easements on 22 properties totalling over 2,500 hectares of land and is now moving into land ownership as a result of legacies left to us by farmers with a dedication to maintaining the resource for future generations.

“In addition to easements, OFT can receive donations of farmland, on which we can deliver programming that provides affordable and long-term leases to new and young farmers, and help ensure the lands are farmed sustainably.”

Don and Deborah Hudson’s farm was the first easement in Prince Edward County. “Our farm has produced food for six generations, as well as providing habitat for many species of birds and animals. We want it to remain this way for future generations, and working with the Ontario Farmland Trust ensures that this will happen.”

With greater public awareness, thanks to the seeds sown by the OFA and other groups, there is more chance that governments will heed the caution signs.

On the sixth-generation Burnham family farm, near Cobourg, succession is fortunately not a problem. Paul Burnham, who is an NFA director, considers himself fortunate that all four of his children have chosen this life. It’s a rarity. They have inherited solid values and a love of farming.

Burnham’s interest in agricultural succession dates back to the 1980s. While on a bus tour, he took note of Pennsylvania’s efforts to preserve farmland. The Pennsylvania Agricultural Conservation Easement Purchase Program now leads the US in the number of acres of permanently preserved land for agricultural use. According to their website, more than 622,000 acres are now preserved.

PEC’s Jason Courneyea puts a family focus on the concept of succession: “Our boys are young and love the farm. Let’s give them the opportunity to do that. If they can’t find the land to do the farming, it’s possible they will move onto different things, and the median age of farmers will just continue to increase. And if that happens, who will feed us?”

LOOKING AHEAD

Joni Mitchell’s lyrics still ring true: You really don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone. What will this area look like in 100 years, or even in the next few decades?

Consider this: At some point during our lifetime, we will require the services of a lawyer, a doctor, a plumber, an electrician and so on. Every one of us requires a farmer every day.

Farming and settlement are both ever-evolving, co-existing ways of life, but although houses are relatively easy to build, the planet is not creating any more new land.

Speaking with the farmers, you see the worry in their eyes and sense the urgency in their written words, but it’s also possible to hear the hope in their collective voices. With greater public awareness, thanks to the seeds sown by farmers and advocacy groups, there is more chance the provincial government will press the pause button, rethink its current policies and protect our farmland.

Story by:

Lynn C. Bilton

Illustration by:

Charles Bongers