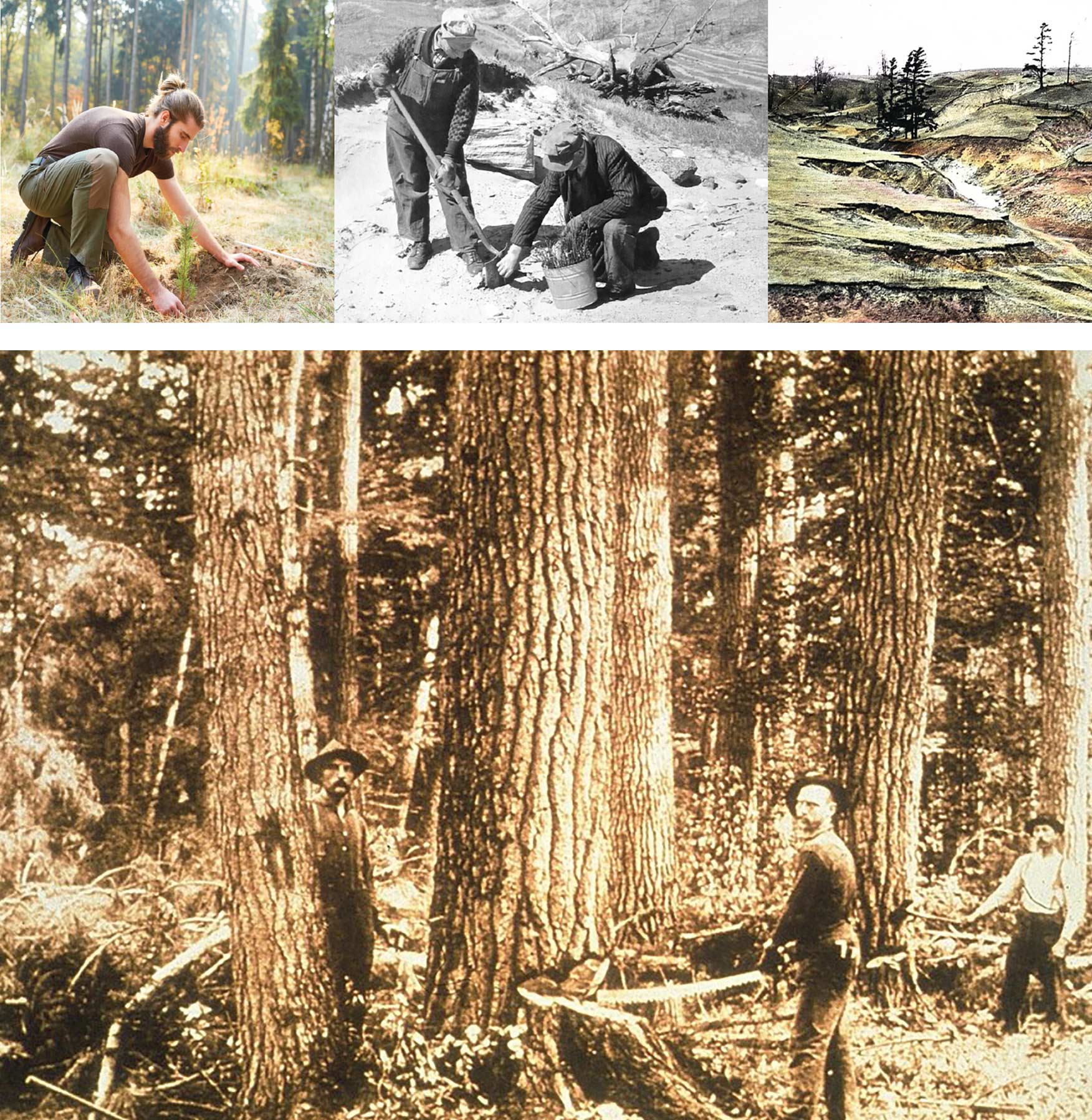

left to right: Reforestation is an ongoing commitment to the environment; men at work in the eroded soils of the Ganaraska watershed in the late 1940s; painted glass slide used to underscore the need for reforestation; Logging in the “pineries” of Upper Canada during the 1800s (Archives of Ontario).

The forest canopies of tomorrow will depend on our efforts today

When we walk through a forest, we like to think of it as a place of serenity. But underneath the quiet, broken only by the calls of songbirds or the rat-tat-tat chiding of a red squirrel, there’s a complex dynamic, one so fundamental the quality of life on the planet depends on it.

We can begin to explore this dynamic with an easily understood relationship – the relationship between forests and water. Walk through your favourite forest at this time of year and you may find the unexpected. Snow. The banks along the county road have long since melted, but in the forest, despite the warm spring sunshine, there are still skiffs of snow and clumps of frozen soil. In the shadows there’s a hint of winter’s chill.

Snow in the forests stretches out the spring melt. Without forests, the melt waters would flash flood rivers in a massive springtime pulse, wreaking havoc on everything from salmon spawning beds to the communities along their banks. Once the pulses pass and the heat of summer arrives, those same waterways eventually dry to mere trickles. The simple capacity of forests to retain winter moisture moderates the spring runoff, releasing water gradually throughout the year.

The forests and their complex structure of root fibres allow winter snow to soak into the ground slowly and eventually find its way into aquifers that supply waterways and wells.

With the lands bare and open, farms replaced the forests and enjoyed good yields until erosion swept away the topsoil, which had been accumulating since the end of the last ice age.

A QUIET CONTINUUM

The story of forests becomes even more interesting when we further consider their relationship with streams. By helping prevent flash flooding, tree roots minimize erosion that can choke the gravel spawning beds of salmon and trout with fine particles of silt.

Fallen trees concentrate flows of water, scouring streambeds to create natural deep pools of cold water fish habitat. Predators that eat those fish spread their nutrients in the nearby forests, fertilizing the trees and shrubs that in turn benefit the streams.

It could be said fish grow from trees and trees grow from fish. One of the fundamentals of water chemistry is that colder water has greater capacity to carry oxygen than warm water. Fish such as salmon and trout have high oxygen needs, so oxygen-rich streams and rivers that have been cooled by shade trees form an important part of a preserved habitat.

Before European colonization, those fish and their predators lived in an environment where mixed forest dominated the landscape, where canopies of deciduous trees such as oak, maple, ash and beech were pierced by “some of the biggest white pine you could ever imagine,” according to professional forester Glenn McLeod.

McLeod, who has worked in local forests since the late 1970s, continues, “Some of the early European settlers couldn’t believe what they were seeing. There was nothing like it left in Europe.” The height of the original white pines can only be imagined. Glenn McLeod notes that early logging took the biggest and best, leaving behind “genetic junk” that gives us some of today’s white pine. These still manage to grow to an impressive height, often reaching 150 feet (45 metres). “Some of the best growing conditions existed at the east end of the Oak Ridges Moraine and into Hastings,” says McLeod. “That area grew fantastic pine.”

LOSING OUR FORESTS

Tree harvesting – with the best wood going to Europe for shipbuilding – began in the late 1700s and continued through the next century. With the lands bare and open, farms replaced the forests and enjoyed good yields until erosion swept away the topsoil, which had been accumulating since the end of the last ice age. McLeod recalls looking over the sandy hills of the Ganaraska Forest with Orono Tree Nursery superintendent Bill Bunting, who told him some of the best topsoil in the province was now “out in the bottom of Lake Ontario.”

“Many people can’t get their mind around what the eroded sand areas really looked like,” says McLeod. “In fact, in presentations I’ve done they look at me as if I’m presenting ‘fake news.’” Floods through the 1900s, including several that inundated downtown Port Hope on the Ganaraska River, and Belleville on the Moira continued the erosion. Hurricane Hazel, which struck the region in 1954 and brought massive flooding, washed a huge volume of topsoil into the lake.

REPLACING WHAT WAS LOST

By the early 1900s the provincial government realized large-scale reforestation was the long-term solution to flooding and erosion. In the 1920s, Premier Ernest Drury established a network of 10 provincial tree nurseries. Nearby, the Orono Tree Nursery opened in 1922, and over seven decades, they supplied as many as six million trees annually to private landowners and for mass planting on sandy, erosion-prone “wasteland” sites throughout the region.

The history of tree planting over the last five decades closely aligns with Glenn McLeod’s career as a professional forester. After studies at Fleming College and Lakehead University, he was hired as assistant supervisor at the Orono nursery and then took on the supervisor role. When the provincial government shut down the nurseries in the mid-nineties, he carried on tree planting as the local coordinator with the Ontario Stewardship program. He retired in 2009 but kept planting with the Northumberland Tree Planters, a group he formed with Laird Nelson, Art Marvin and Bill Newell. Since 1996, McLeod and his partners have put 1.5 million trees in the ground.

Funding sources for tree planting tend to come and go with changing government priorities. These days the main funding source in the province is Forests Ontario, a non-profit charity that receives federal money and also fundraises for its 50 Million Tree program. Chief Executive Officer Rob Keen says Forests Ontario’s goal is to establish at least 40 percent tree cover in Southern Ontario, the amount required to ensure healthy forests that can withstand stresses such as climate change. “The best scenario is to have large, healthy contiguous and diverse forests,” he says. Every year Forests Ontario supports the planting of 2.5 to 3 million trees, working with 500 to 600 landowners.

PLANTING YOUR OWN

Landowners interested in planting 500 or more trees can work with Forests Ontario by registering on its website. They’ll be put in touch with a local partner for a site visit to determine which trees would best suit the property and address the owner’s priorities.

Forests Ontario provides subsidies that support most of the planting costs, however, the landowner may be required to contribute financially or inkind. Local conservation authorities may also offer smaller numbers of native plants and shrubs for those unable to meet the 500 tree requirement. Other funding programs are available for projects that support specific conservation goals. These programs include Ganaraska’s Clean Water Healthy Lands program, Quinte Conservation’s agricultural watercourse buffer planting program, and Lower Trent’s clean water stewardship program.

Tree planting programs emphasize native trees grown from regionally collected seed. “That’s the tree that fits our local soils, our climate the best,” says McLeod. Ecologically, native trees support the insect and animal populations that have evolved with them over thousands of years. Climate change is putting a slight wrinkle in the approach. Concerned about the future stresses of a warming climate, foresters are starting to plant a small percentage of trees from the next climate zone to the south – Niagara or Upper New York State in our case.

The reasons for planting trees are as individual as the landowner. Some plant for privacy, some for wood production, and others to leave a legacy for future generations.

CREATING DIVERSITY AND FACING CHALLENGES

While there’s solid funding support for tree planting, other challenges remain. One is woodlot maintenance. Reforestation projects typically plant conifers such as pine, larch and spruce densely in rows, at 600 to 800 seedlings per acre, hoping they will quickly establish cover and crowd out competition. After two or three decades of growth, best practice is to thin these trees to give the strongest ones room to grow. “You can’t grow great big trees six to eight feet apart,” says McLeod. Thinning also creates gaps where deciduous trees can establish themselves, creating forest diversity as their seeds are carried in by birds and small animals.

Whether landowners do the necessary maintenance is hit and miss. “It’s a big issue,” McLeod comments. Some landowners are involved almost monthly, with activities such as thinning and installing nesting boxes, while “others haven’t done a darned thing,” says McLeod. Landowners close to the major forests may be able to take advantage of mechanized row thinners brought in for large tracts. Other landowners are on their own.

Invasive plant species such as dog-strangling vine and European buckthorn are another challenge as they compete with tree seedlings for sunlight and moisture. And a legion of foreign diseases and pests means the American ash, American chestnut, butternut and beech trees that once populated the original forests of the countryside won’t be part of the forests being planted now, at least not in our lifetime. A looming concern is the woolly adelgid, an Asian insect that attacks the eastern hemlock tree. It has been found in eastern North America and is headed our way.

The good news is that researchers are beginning to find some answers. McLeod notes the Canadian Food Inspection Agency has released a parasite that attacks dog-strangling vine, although it might be five to ten years before we see its benefit. Given enough time, and perhaps a bit of help from humans, tree species can recover from diseases and pests. Plant pathologists in the United States are developing a blight-resistant American chestnut. The Elm Recovery Project at the University of Guelph has identified Dutch elm disease-resistant specimens across the province, and is distributing their progeny to orchards in hopes of spreading the genes that will grow future generations of healthy trees.

TAKING ROOT

Tree planting season is a short window between when the ground becomes frost free and the first buds break on trees, so larger plantings for this year are already fully committed. If you contact Forests Ontario or your local conservation authority this spring or summer there will be plenty of time for someone to come out and help you put together a plan for 2024.

One person you won’t see is Glenn McLeod. He and his partners, two of whom are now 75, are getting out of the tree planting business, having sold most of their equipment to Jordan Rolph, a forester who operates Mastwood Consulting in the Bewdley area. Another forester, Steve Pitt, provides tree planting services for Prince Edward County and the southern portion of Hastings.

“It is time for younger legs to take up the torch,” says McLeod. “We have sold two of our mechanical planters, leaving us with one planter and one tractor. Bill Newell says it’s just in case we want one more hurrah.”

“They’ve got a remarkable history of planting forests,” says Rob Keen, speaking of the Northumberland Tree Planters team, which was given the MVP – Most Valuable Planters – award at the Forests Ontario conference in February.

The most valuable partnerships are always between trees and humans.

A Legacy Of Trees

Those of us who grew up in rural Ontario will remember fondly the native maple trees once common along country lanes. These trees provided habitat and scenic enjoyment, blocked snow, prevented erosion – and in the case of some species – provided the sweet taste of maple syrup. Farmers planted those maples in the late 19th century in return for a government incentive.

A hundred and fifty years later many of these trees have disappeared from the landscape. Maple Leaves Forever, a charity that promotes the benefits of native maples, is bringing them back by providing a 25 percent rebate to landowners who plant red, silver, sugar or Freeman maples. Founded by entrepreneur Ken Jewett, Maple Leaves Forever has supported the planting of more than 130,000 native maples, on the equivalent of 1,200 kilometres of road and laneway.

Trees eligible for the rebate must be at least five feet (150 cm) in height. Qualifying landowners plant ten to 50 trees per year, a minimum of 25 feet (7.6 metres) apart. Landowners interested in the program can find details and apply online through the Maple Leaves Forever website. Deadlines are May 15 for spring planting and November 15 for the fall.

Story by:

Norm Wagenaar