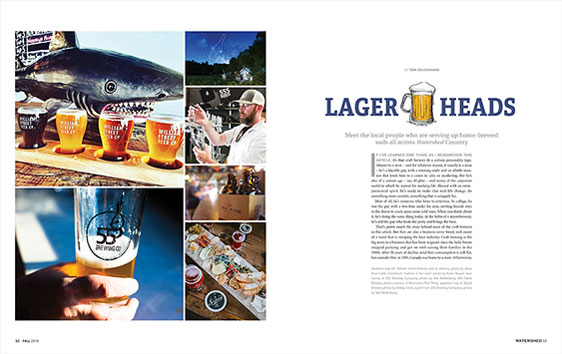

Meet the local people who are serving up home-brewed suds all across Watershed Country

IF I’VE LEARNED ONE THING AS I RESEARCHED THIS ARTICLE, it’s that craft brewers fit a certain personality type. Almost to a man – and for whatever reason, it usually is a man – he’s a likeable guy, with a winning smile and an affable manner that lends him to a career in sales or marketing. But he’s also of a certain age – say, 40-plus – and weary of the corporate world in which he started his working life. Blessed with an entrepreneurial spirit, he’s ready to make that mid-life change, do something more creative, something that is uniquely his.

Most of all, he’s someone who loves to entertain. In college, he was the guy with a two-four under his arm, inviting friends over to the dorm to crack open some cold ones. When you think about it, he’s doing the same thing today. At the helm of a microbrewery, he’s still the guy who hosts the party and brings the beer.

That’s pretty much the story behind most of the craft brewers in this article. But they are also a business-savvy breed, well aware of a trend that is sweeping the beer industry. Craft brewing is the big news in a business that has been stagnant since the baby boom stopped partying and got on with raising their families in the 1980s. After 30 years of decline, total beer consumption is still flat, but consider this: in 1985, Canada was home to a mere 10 breweries, of which three owned about 90 percent of the market. Something changed, because in 2010, there were 310. Last year, the number passed the 800 mark. Virtually all the growth has been among craft breweries, also called microbreweries. These are small, upstart businesses, none of which ever hope to match the corporate giants but brew their own signature beers in small batches for a local market. Their focus is as much on artistry as it is the bottom line. They prefer traditional ingredients and eschew factory methods in favour of artisanal skill. More than one told us, with true independent spirit: “We don’t care if we make the most beer. We just want to make the best.”

Nation-wide, microbreweries rang up $88.5 million in sales in 2016, up an astonishing 27 percent from only the year before. While this sounds like a bonanza, it’s pretty small potatoes, considering that craft brewing accounts for only 7.6 percent of the total beer market in Canada. Still, this is up from four percent in 2013. In an industry where one percent of market share represents about $15 million, don’t think that the corporate giants aren’t watching. Coors Light may still reign supreme, but it’s the little artisanal guys who are driving the beer industry these days.

Here in Watershed country, whose last homegrown brewery closed before Prohibition, a new age dawned with the opening of Church-Key near Campbellford, the region’s first microbrewery, in 1999. Today, it is joined by no fewer than 16 more (count ’em – a total of 17!), two of which have yet to officially open their doors to the public. Perhaps not surprisingly, many are concentrated in the County, where the down-home vibe and abundant tourist traffic are perfect for the craft brewer. What might be surprising is the extent to which their business models vary. From bustling bistro-pubs to warehouse-style tasting rooms, they show remarkable variety in their approach to sales. The fun lies in finding the brew you like best.

There was a time when every brewery was a craft brewery. For hundreds of years, commercial brewers practiced their age-old trade much the way their ancestors had. They made their ale – and it was usually ale, not lager – in small batches. Like their descendants in today’s craft brew industry, they used available ingredients, all sourced locally, and their beer rarely went any farther than the local tavern.

Back in the day, breweries were one of the first businesses to appear in fledgling settlements, largely because it wasn’t wise to trust the water. One of Cobourg’s founders – James Calcutt – established a brewery as part of a larger milling complex in the 1830s. Picton had a brewery teetering on the north bank of the harbour, overlooking the site of today’s yacht club. In 1844, when Port Hope was home to a mere 244 people, it already had a commercial brewery. Only seven years later, it had another, run by the Molson family… yes, the Molson family, who established a “branch plant” of their Montreal brewery on the Ganaraska River.

None of these ventures would survive, thanks to innovations such as the railway, the bottling process and refrigeration, which greatly favoured the economies of scale of established brewers in the cities. But even they weren’t bulletproof against Prohibition. By the time booze and beer were legal again in 1927, the larger breweries could greatly out-produce the smaller ones, which were either absorbed by the corporate giants or fell by the wayside.

And as the industry became more standardized, so did its product. Gone were the hoppy, full-bodied, traditional ales in favour of light-tasting, mass-market brands. By 1960, “advertising was driving the industry, not taste,” reflects Drew Wollenberg of 555 Brewery in Picton, noting it was the same with baked goods, cheese, and everything else in the food and beverage industry. Indeed, the post-war palate went bland.

But this alone doesn’t explain the beer aficionado’s disdain for industrial beer. Corporate suds often employ ingredients – GMO grain, fructose and even rice – which are enough to make the purist shudder. Says Sean Walpole of the William Street Beer Co., “Beer should only have four ingredients: water, malted barley, hops and yeast…in that order.” For the artisan, the skill is in concocting a recipe that blends these ingredients to produce something genuine, tasty and about as far from conventional brew as you can get.

It was in the early 1980s that the first wave of microbreweries opened their doors to a thirsty clientele of boomers, but the real sweep came at the turn of the millennium, when a new generation came of age. Millennials, whose consumer ethic embraces natural, home-made products, are the ones driving the microbrewery boom. When the bubble bursts is anyone’s guess – more than one industry pundit has suggested that we are already at “peak beer” – but for now, the sky’s the limit. It’s a wonderful time to be a beer drinker.

WILLIAM STREET BEER CO., COBOURG

Opened: 2015, new location 2017

Concept: Tap room and retail sales with the brewing equipment in full view.

Setting: In a plaza location in Cobourg’s west end. Shares a parking lot with M&M Food Market, an organic supermarket, the UPS Store and Pizza Hut.

Signature Beers: Four in-house brews, including a lager, a blond, an amber ale and a pale ale. Other beers subject to seasonal availability.

Stroke of Genius: Start small. Take it slow.

Sean Walpole is a textbook example of the hobby brewer who turned pro and found his niche in the craft beer biz. Looking back to turning 40, he remembers the tug that prompted him to leave both his job and the city behind. “I was in sales but wanted to do something on my own. Meanwhile, my wife, Karen, and I were itching to get out of Toronto,” he recalls. “It was time to make the change.” He had the brewing skills, but says it was a big step to go commercial. “I was making about 100 litres a year for parties, for entertaining. Opening a craft brewery would be an all-consuming leap.” Nowadays, he routinely brews between 3,000 and 4,000 litres a month.

Sean scoped any number of small-town locations around the GTA, eventually settling on Cobourg, recalling childhood days spent visiting relatives here. “We looked at Port Hope, too, but it all came down to finding a suitable location that was available.” They set up shop in a former gas station on William Street, which ultimately proved too small. Last year, Sean moved the business to a larger location in a busy plaza with plenty of parking spots just up the road.

“The secret to success has been to grow gradually and build a loyal clientele,” he advises, adding that the plaza location has been a godsend. “We have a great after-work crowd, and as word gets around, we get more and more sales off the street.”

975 Elgin Street West at William Street, in the Victoria Place plaza, Cobourg

SIGNAL BREWERY, CORBYVILLE

Opened: 2017

Concept: “Destination” brewery and eatery with selections that go well beyond the choice between lager and ale.

Setting: Fabulous riverside locale in repurposed industrial buildings, just north of Belleville.

Signature Beers: At least eight original brews on tap at any time, from conventional pilsner and Mexican- style light to exotic fruit-tinged stout and IPA. Bottle sales too.

Stroke of Genius: Radio Tube, Byte, Ohm, Gamma Ray: all of Signal’s brands have an electrical zing to their names.

Without question, Signal is the most ambitious enterprise of its kind in Watershed country. At its heart, this is a brewery, but Signal is also a banquet facility, an event venue and a restaurant. It has a staff of almost 40, including a couple of expert brew-makers. Built on the remnants of the abandoned Corby-Wiser distillery on the banks of the Moira River, it boasts a riverside patio that seats 60, and adjacent are several beach volleyball courts. Plans call for the installation of a dozen or so yurts along the water’s edge. Fly fishing is on the agenda. And when the river is high enough, Signal offers customers the opportunity to float down the Moira in an inner tube, with a cold brew awaiting at the end of the dabble.

Owner Richard Courneyea quickly understood that if it was going to succeed, Signal needed innovative – even offbeat – ways to attract customers. “We are in a rural, out-of-the-way location,” he explains. “There’s no foot-traffic, so we have to make ourselves a destination.”

Of all the brewery owners we interviewed for this story, Richard is the one who doesn’t quite fit the mould. Coming off 27 years as the owner of an upscale men’s clothing store in downtown Belleville, he bought the Corby site because he admired its heritage character and saw some possibilities. “My first inclination was to use the old buildings as the basis for a condo development,” but after crunching some numbers and a lot of blue-sky thinking, the brewery came into focus. “There’s something poetic about making beer here,” he says. “After all, Corby’s went back to the 1840s on this very site. In a way, Signal is continuing the tradition.”

86 River Road, Corbyville (north of the 401/Hwy. 37 interchange in Belleville)

FRONTERRA FARM BREWERY, HILLIER

Opened: To be announced

Concept: Very small-scale producer whose goal is to provide unique brew to discerning customers. Setting: Wonderfully isolated 58-acre waterfront farm in western Prince Edward County. Also offers luxury camping and farm vacations.

Stroke of Genius: Takes “local” to new lengths. Every ingredient – barley, hops, yeast and water – will be sourced directly from the farm. What “farmto- table” is to local cuisine, “plough-to-pint” is to Fronterra beer.

Anyone who knows a Chardonnay from a Chablis knows that the characteristics of wine are largely determined by “terroir,” a sometimes elusive set of environmental factors such as elevation, microclimate, the nature of the soil, exposure to the sun, and proximity to a body of water.

The same grape can yield an exceptional variety in flavour, depending on where it is grown. And so it is with beer, according to Jens Burgen, who, by the time you read this, hopes to unleash his first batch of commercial beer from his venture called Fronterra Farm. With this in mind, Jens doesn’t really know how his beer will taste, and isn’t going to steer it in any particular direction. “It will be determined by the terroir,” he explains, noting that his little corner of the County has proven to be excellent ground for growing barley. “I expect my beer to be ‘barley forward,’” that is, strong on barley flavour.

To that end, he has 12 acres in production. He also grows four varieties of hops, again reasoning that these, too, will be a factor in creating something special. Even the water – from his own aquifer – is part of the terroir philosophy. “The beer will be unique, very much our own.”

If the other breweries in this article are microbreweries, Fronterra might be better called a “nanobrewery.” It never hopes to grow big, but will carve its niche among sommeliers, chefs and connoisseurs. It’s been an uphill battle. Last year’s barley crop was wiped out by mildew and the hops withered during a late-summer drought. Fortunately, things are looking better for 2018. Something tells us it’ll be worth the wait.

242 North Beach Road (County Road 27), south of Consecon

555 BREWING CO., PICTON

Opened: 2017

Concept: A “local” that brews its own.

Setting: Storefront location in the heart of downtown; takes advantage of its front courtyard by offering plenty of patio seating, an outdoor pizza oven and even a sandbox for the kiddies. Offers food and draft; take-home sales, too.

Signature Beers: At least six varieties on tap, from crowd-pleasing lager and IPA to an exotic black ale and a beer/cider blend.

Stroke of Genius: The Judge; The Jury, The Executioner: Brands acknowledge an infamous 1884 murder and trial that is now part of County lore.

Drew Wollenberg was already a hobby brewer when he and his wife, Natalie, were playing in a band together in Perth, Australia. For Drew, life in Oz was a long way from home, but when two toddlers were suddenly underfoot, he felt the pull to be closer to family back in Prince Edward County. So the couple gave up their careers – he in IT; she in nursing – and moved halfway around the world to Milford. But how to pay the rent?

Drew’s brewing pastime began simply as a way to make cheap beer but evolved into something he was passionate about. Moreover, it proved their salvation. In 2015, Natalie and Drew opened the County Canteen, a gastro-pub on Picton’s Main Street, which currently has 26 craft beers on tap, including Drew’s own. But the couple quickly started looking for a second location with more brewing capacity. And at the opposite end of Main Street, they found it in a storefront a little farther uptown. Bonus: it had a forecourt that could be turned into a lovely beer garden.

555 is a small-town effort that has no illusions about going corporate. “We want to be the best ‘local’ in Picton,” Drew says. The clientele is largely townsfolk, but the pub definitely benefits from the vast amount of tourist traffic in Prince Edward County’s main town. “I like the German model, where every town has its own signature beer. It can work here, too.”

124 Main Street at Chapel Street, downtown Picton

MORE LOCAL SUDS

In addition to the breweries profiled in this article, Watershed Country is host to several others. Some are fledgling operations; others have several years behind them. Rarely do they sell through the LCBO – but you can sample at selected bars or buy directly from the brewery.

Barley Days Brewery

www.barleydaysbrewery.com

Bickle Farm Valley Hops

(Facebook only) @ValleyHops

Celtic Brewery

www.celticbrews.com

Church-Key Brewing Co.

www.churchkeybrewing.com

Lake on the Mountain Brewing

lakeonthemountainbrewco.com

MacKinnon Brothers Brewing Co.

www.mackinnonbrewing.com

Midtown Brewing Co.

midtownbrewingcompany.com

Napanee Beer Co.

napaneebeer.ca

Northumberland Hills Brewery

(Facebook only) @TheNHBbrewpot

Old Flame Brewing Co.

oldflamebrewingco.ca

Parson’s Brewery Co.

www.parsonsbrewing.com

Prince Eddy’s Brewing Co.

www.princeeddys.com

Wild Card Brewing Co.

wildcardbrewco.com

Story by:

Tom Cruickshank